Gordon Gekko, Mr. Burns and Scrooge McDuck are some well-known Hollywood representations of the "rich, bad" person who, so consumed with greed, shows no compassion and has no morals. Sure, one might say that not all who are ridiculously wealthy deserve to be placed in the same category as those greedy, selfish and unkind fictional tycoons; that those are merely caricatures. Or perhaps it is a case of cognitive dissonance, where audiences prefer to think negatively of the rich because everyone secretly wishes they were rolling in money too. The fundamental question, however, is if there are grounds to believe that money causes people to be less humane, less happy and ultimately, evil. This was a topic that Christie Scollon had sought to address at a recent Social Sciences Capstone Seminar, titled 'Is Money Evil?'

An associate professor of psychology at SMU's School of Social Sciences, Scollon first asked her audience to list a couple of mundane, everyday things that made them feel happy. "Ice-cream," someone said. "Facebook!", "Long showers", "Catching a bus just in the nick of time," others chimed. It is not difficult to imagine that people might be willing to give up some of these simple pleasures in exchange for money, or that for enough money, people might be willing to do things that they would not otherwise do – things that may be ignoble, unkind, or downright evil, Scollon noted. "[The common belief] is that people will do all kinds of wrong in order to have more money, from the stories on Wall Street to the people who put melamine in the milk powder; people who cheat, steal and lie just to get more money." What is evil, however, is a judgement best reserved for the morally divine.

Giving money the evil eye

Scollon opted to focus on two religions for their views on the subject. Starting with the bible, she shared how the association between 'money' and 'evil' might have been introduced through Christianity. For one, Timothy (6:6-10) says, "For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil." This idea is reinforced in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus – a story where Lazarus, a beggar in life, enjoyed a rich afterlife in heaven, whilst the rich man, who already enjoyed a life of wealth, burnt for eternity in hell. The Quran, by contrast, seems far less critical. It preaches that wealth is a blessing and that the enjoyment of wealth is acceptable as long as it is spent in the right way; on family, friends and religious causes, Scollon noted. But with various interpretations of religious edicts floating around, it seems there is hardly a conclusive take on the absolute 'evilness' of money.

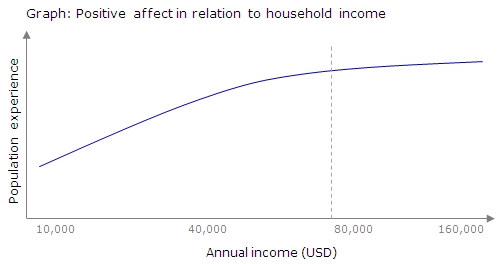

An interesting analogy on the subject, however, was once offered by the son of a wealthy businessman. Money is like beer, he suggested, because drinking beer feels good, but only up to a certain point. Beyond that "sweet spot", utility diminishes quickly. "In a similar way, money might bring you some happiness, but beyond that magic point, any additional income isn't going to make you happier," said Scollon. That magic point has, apparently, been deduced as approximately 75,000 USD a year, she added, citing a recent study by two Princeton University researchers who looked at the data of approximately 450,000 Americans. What they found was that as income increased, emotional well-being also went up, but the line flattened out from the $75,000 mark.

"Perhaps $75,000 is a threshold beyond which further increases in income no longer improve individuals’ ability to do what matters most to their emotional well-being," the study reported. This means that people in the US who make $75,000 a year (around 8,000 SGD per month) are just as happy as those who make $150,000. Any higher income is not going to increase emotional well-being, but a lower income is associated with less emotional well-being, Scollon explained. Yet, a salary of S$8,000-a-month may still seem measly to some. Those who lead extravagant lifestyles and have easy access to money might even scoff at the idea that they can live happily or comfortably with that amount. Plus, what could be so wrong with asking for more?

Rich dad, poor kids

Alluding to capitalism and materialism, John Keynes once wrote, "The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease." The renowned economist might have a point, for psychology also paints a pretty grim picture of materialists, said Scollon.

Materialism, defined as valuing money more than other things (e.g. friendship), often leads people to be less happy; and this is the prevalent conclusion across most studies, she added. "They have worse mental health and they are more depressed. They have worse social relationships. They have lower social productivity, so they are less likely to participate at social events and civic organisations. They have lower attitudes towards marriage and children. They have less concern for the environment; they might be more wasteful and less inclined to recycle. They are more Machiavellian in their outlook; more narcissistic. They have less empathy and are less likely to cooperate."

Dismal as it may seem, materialism frequently receives a glossy window-dressing through celebrities and popular television shows like Gossip Girl, 90210, and Keeping up with the Kardashians. Characters from many of these (fictional and non-fictional) shows are often rich, young, attractive and popular. Enviable lifestyles of opulence and glamour aside, many of these adolescents are portrayed to have deep personal and social problems – the stuff of good television melodrama – much of which may not even be due to the wild imaginations of creative scriptwriters. In fact, a good amount of research has shown that rich kids experience surprisingly high rates of social issues, ranging from eating disorders, depression and anxiety to substance abuse and vandalism, said Scollon.

Why are rich kids more prone to social problems? Easy access to money and a lack of parental supervision are perhaps the more obvious contributing factors. However, many of these adolescents also face extraordinary pressures owing to their inherited social status. "They come from affluent families and they face a lot of pressure not just to get into university, but to get into one of the top universities. They aren't just expected to play sports or engage in extracurricular activities; they are expected to be captain, to excel. So as a result, they often have over-scheduled lives, and they go from one scheduled activity to the other; that wrecks their ability to form naturally occurring friendships that just happens when you hang out with people," Scollon explained.

Is the self-sufficient materialist going to heaven?

Past studies show that money has the effect of making people less social. Scollon raised examples of various lab experiments where it had been observed that respondents primed with thoughts of wealth and money were less generous with both time and money, compared to respondents who were neutrally primed. They were less helpful, less willing to ask for help, preferred less social contact, donated less money, and preferred to work alone on tasks. On the other hand, the notion of money made respondents feel stronger, and buffered them from the negative effects of social rejection and physical pain, she noted. This sense of self-sufficiency is perhaps activated by a "market-pricing mode", where life is thought of in transactional terms.

"Money enables people to achieve goals without aid from others," said Scollon. It comes from the belief that money is the "ultimate problem solver"; that there is no obstacle too daunting that money cannot tackle. In this "market-pricing" conception of the world, everything and every action has a price-tag. Personal performance is emphasised here, over and above social connectedness – because money tends to be associated with personal reward for success. "There are two ways in life to get what you need from the social system. One is to depend on other people – and this is the more traditional way, where in hunter-gatherer societies, the way to get what we need is to rely on others – and the other is through money," she added.

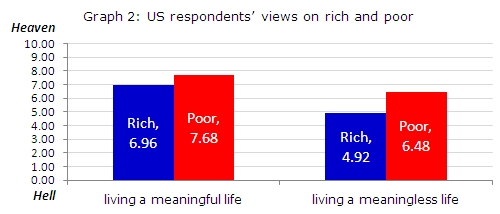

Despite the generally negative perceptions of materialists as egocentric, selfish, unkind and antisocial, Scollon found that people in Singapore seem to take comparatively well to those who love money. For her study, respondents were given a life-evaluation survey form supposedly filled out by someone else, following which they were asked to evaluate how likely they thought this 'person' would go to heaven. The forms were, of course, filled out systematically by Scollon to embed characteristics that she had set out to test. Some respondents viewed a survey that looked like it was completed by someone who did not make a lot of money, and others, a survey that looked like it was completed by a wealthy person. The forms also contained information that indicated if this fictitious person led a meaningful and happy life.

On a scale of 1 to 10, respondents rated how likely this person would go to heaven, 10 being most likely going to heaven. Scollon found that Singapore respondents were largely indifferent on both the rich and poor who led meaningless lives. However, the poor person who leads a meaningful life was rated slightly higher than the rich counterpart. This was observed amongst US respondents as well, albeit with a greater contrast. US respondents gave their lowest rating to the rich person with a meaningless life, whereas Singapore respondents thought most poorly of the poor person with a meaningless life. Nonetheless, it was felt across both studies that the poor person leading a meaningful life was most well-deserving of a place in heaven.

Money buys happiness

Money can buy some pretty fine experiences, from luxurious abodes and travels to art, beautiful clothes and good food. We also know that money can make people feel happy – up to a certain point: 75,000 USD. An interesting question to ask, however, is if people's ambitions to accumulate wealth might impinge upon their ability to savour the everyday pleasures – the mundane things that were identified at the start of the lecture. Will a life of opulence undermine a person's ability to enjoy simple things like "ice-cream", "Facebook", "long showers", or "catching a bus just in the nick of time"?

Scollon mentioned a past study by researchers at the University of British Columbia in which two groups of participants were treated to chocolates. One group was primed with money, and the other was exposed to a neutral condition. Both groups filled out a survey on how much they enjoy eating chocolates, and then they proceeded to eat chocolates. Observers watched and timed the participants. What they found was that the group exposed to notions of wealth and money beforehand savoured the chocolates less and ate much faster, compared to the control group. But while this study's findings go towards supporting the argument that money diminishes the joys we derive out of the simple pleasures, Scollon noted that overall, money can still have a more positive than negative impact on people's lives. Sure, a person might enjoy "ice-cream" or "Facebook" less, but "people with money have better nutrition, better health, longer lives; they have more leisure time, more time to spend with their family and friends; all of which contribute to happiness," she said.

People with money get to enjoy greater choices, on how they spend their time and resources. "They spend more time doing things that they want to do, less time on drudgery. And of course, on top of all of these things, rich people have nicer shoes," she quipped. "Wealthier countries also have cleaner water, better infrastructure, less disease, and as a result of less disease, people have higher IQs." The paradox, Scollon pointed out, is that wanting money seems to make life worse but having money seems to make life better. How do we make the best out of the situation? The secret may lie in the way we spend our money.

Some studies have shown that people derive longer-term satisfaction when they splurge on experiences, rather than on accumulating possessions. Other studies have shown that people derive greater joys when they spend on others, rather than on themselves. Here, Scollon spoke of a study in which participants first filled out a survey to measure their own happiness levels, following which they were then given either $5 or $20. Some participants were instructed to spend on themselves and some were told to spend on other people.

What the researchers found was that spending on self led to no increase in happiness, regardless of whether participants received $5 or $20. However, participants who were told to spend on others registered an increase in happiness. "And it didn't matter if they spent $5 or $20 on others. The increase in happiness was the same," Scollon reported. What this tells us is that spending money on others can lead to happiness for the spender – and the amount of money spent is not a significant factor. So to increase happiness, the trick is to simply spend some amount on other people, she concluded.

Last updated on 27 Oct 2017 .