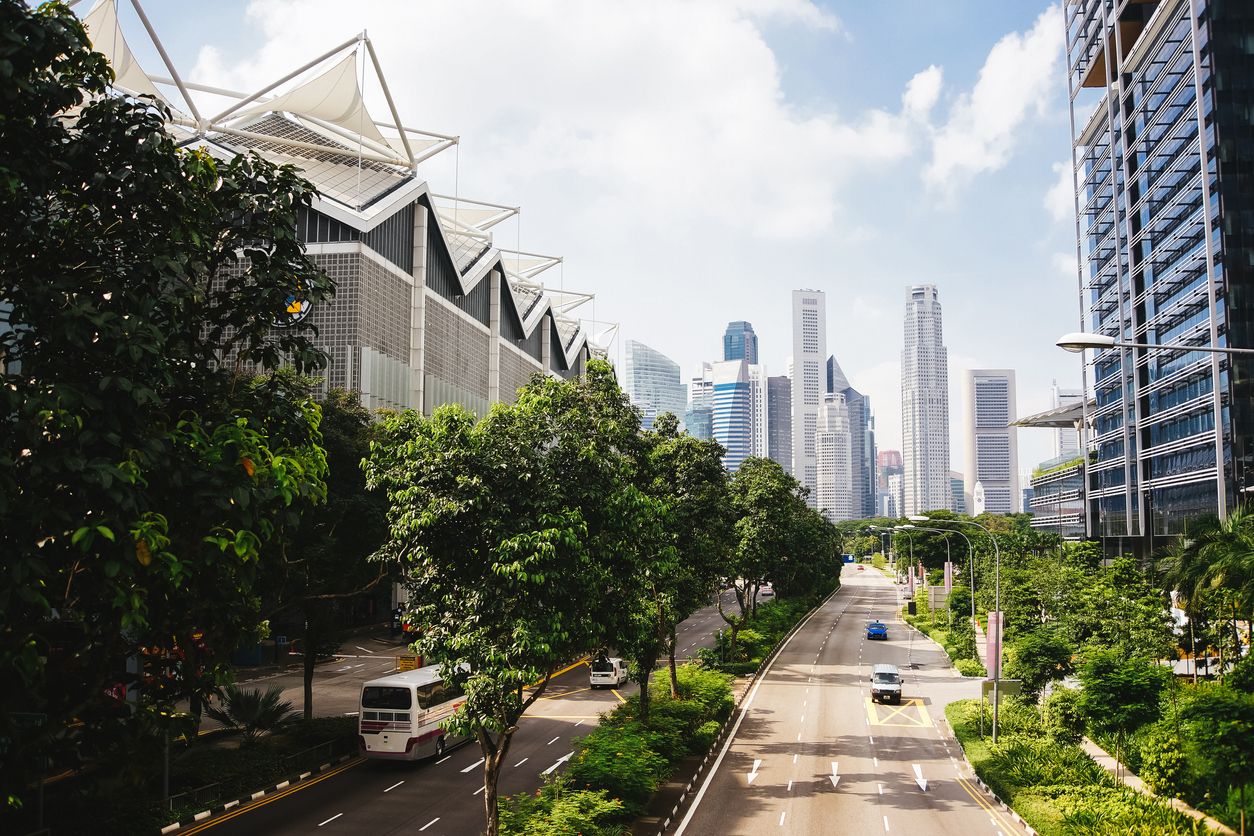

Singapore strikes a balance between competing needs to address climate change challenges

Nearly two and a half years into the global COVID pandemic, remote working is expected to become a permanent feature of work, if only on certain days of the week. The questions of re-sizing office space, and relocating to minimise commutes, have gained urgency.

In Singapore, where efforts to move companies away from the Central Business District (CBD) have seen reasonable success, post-COVID commuting patterns could pave the way for sustainability initiatives.

“Today, most of the jobs are in the CBD and in the industrial estates in western Singapore,” observes Ng Lang, Chief Executive of Singapore’s Land Transport Authority (LTA). “A lot of traffic comes into the CBD on a typical workday. This is something we’ve been trying to change for the last 20 years. Ideally you could get to your office with minimal travel, or even walking.

“With COVID, we might be able to do this. The last three years have demonstrated that you don’t have to be in the office all the time. It’s an opportunity to change mindsets, making people set up offices near their homes. This reduces transportation carbon emissions.”

A green plan

Ng made those remarks at a recent Mapletree Leadership Series lecture titled “Planning for a Sustainable City” where he cited other government efforts to curb carbon emissions. From generous electric vehicle (EV) rebates that go up to S$45,000 – “Every time you switch from an ICE to an EV, you halve emission,” Ng points out – to the ending of sales of all internal combustion engine (ICE) cars by 2030, electrification is the “way to go”.

To make it work, thorough planning is required. The building of charging stations is a clear example.

“The target is 40,000 public carparks to be fitted with charging stations, and 20,000 private carparks in places such as malls and condominiums,” Ng elaborates. “It’s a public-private partnership. Because we need to support the chargers, we have to strengthen the power grid connected to the chargers. The private sector builds the chargers, the government upgrades the power grid.”

These targets are part of the SG Green Plan, which also calls for building of more green spaces and adapting to rising sea levels. At the heart of how Singapore’s city planners manage 720 km² to satisfy competing needs – housing, military, transport, water catchment etc. – is the long-term plan, sometimes referred to as the Concept plan.

“Singapore is the only island city-state in the world,” Ng explains. “Most cities just need to plan for the needs of the city. But in Singapore we have to plan for the needs of the state. We had to plan for things like defence, which takes up 20 percent of our land mass. We have to plan for water catchment. Whereas most cities have water catchment outside the city, here we use the city itself as catchment.

“With the long-term plan, we look at land use for the next 40 to 50 years. We started the first one in 1971, it was called the concept plan, which was revised every 10 years. We bring half the government together to debate land use to meet the competing needs.” He continues:

“The long-term plan is then translated into the master plan. This guides the development of the city over next 10-15 years. We work in partnership with the private sector, and this is done through land sales programmes to private companies who buy land from the government.

“When we sell land, we do so with conditions. We would stipulate requirements such as connecting to the next building, or to the MRT station, or build a small park next to the building etc.

“We also have something called development control guidelines. Every plot of land on the master plan has a set of development control guidelines that stipulate things such as the building’s height and plot ratio, and it’s through these guidelines and land use conditions that we shape the city that we want.”

Sustaining the economy for sustainability

The ability, and perhaps more importantly, willingness to take hard decisions typifies the Singapore city planning experience. From reclaiming Marina Bay in the 1970s and then leaving it unused for two decades in anticipation of expected growth, to moving the then-biggest port in the world to the western part of island while it was still working fine, one could not accuse city planners of navel-gazing.

In a Q&A session, Ng was asked if Singapore’s city planners might be looking at declining birth rates and relax the city’s compact structure, building more open spaces instead of 50-storey public residential blocks. The former CEO of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) cites the Japanese experience.

“Some towns have disappeared, and the Japanese sometimes joke that by a certain year the Japanese population would be down to one man,” he quips. “Part of sustainability is that the economy must prosper. I have not seen a city whose population has declined but it continues to do well.

“How is Singapore’s population going to sustain paying taxes to support an older population? These are important questions. My conclusion is that we must continue to let immigrants in.”

Ng Lang was the speaker at the Mapletree Leadership Series lecture “Planning for a Sustainable City” that was held on 21 April 2022.

Follow us on Twitter (@sgsmuperspectiv) or like us on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/PerspectivesAtSMU)