What do successful managers have in common?

The truth is—apart from being great in their jobs, many successful managers often credit their success to someone, somewhere along the way—who not only gave them a pivotal career break, but also pushed them, inspired them and helped them grow.

Such is the story of Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, who got a shot working at Google when Eric Schmidt, the then CEO of Google, asked her to get on board the ‘rocket ship’;1 or that of many other successful managers who we spoke to in our recent study of 40 managers and 100 global senior leaders.

Take the example of Yen, a successful executive at a market leading multinational. When asked about how he got to where he is, he credited his success to David, his very first manager—who not only gave him opportunities to work in multiple domains from engineering to finance, operations, sales and marketing—but also provided the opportunity for this young rising talent to earn an MBA at the prestigious University of California, Los Angeles. Or Jac, who rose rapidly from being an employee relations officer to a senior director of a major institution because there were people throughout her career who gave her multiple opportunities to learn and grow—whether this was to lead the HR department in a global organisation or hire 10,000 people from scratch in a subsidiary of Singapore’s investment company, Temasek Holdings.

Whether you talk to a successful manager in the United States, Asia or anywhere in the world, you will find similar stories. Successful managers get to where they are because there were people who gave them guidance, personal counselling and opportunities. People who gave them exposure and stretch assignments. People who advocated for them and fought for their promotion. People who opened doors for them, expanded their networks, and developed their leadership skills. These are the people whom Sylvia Ann Hewlett, the founder and CEO of a successful think tank, the Center for Talent Innovation, calls sponsors’.2

Undoubtedly, hard work gets you far in your career. However, having a sponsor can get you further. Hewlett certainly knows the importance of having sponsors. One of her sponsors, Harvey Picker, helped her to land a top job at the Economic Policy Council (EPC) in New York by recommending her to the chairman of the EPC while highlighting her credentials as a top-notch academic with international exposure.3

Establishing what sponsors do is the first of the three related objectives we hope to accomplish in this article. We describe how sponsor relations are developed and what prevents them from occurring. Finally, we’d like to give managers a framework for establishing sponsorship programmes.

What sponsors do

Sponsors are often confused with mentors, but they perform a different set of tasks in the success of rising talent. While mentors give advice, direction, and emotional, psychological and social support,4 or could be role models,5 they often fall short of making a significant difference in your career because mentors are not accountable for your success. They also typically do not have the power to help you advance.

In contrast, sponsors are people in positions of power. They are senior leaders who stick their necks out for you. They are both accountable for and committed to your career success. And they spend time investing in your career. In other words, mentors give and sponsors invest.

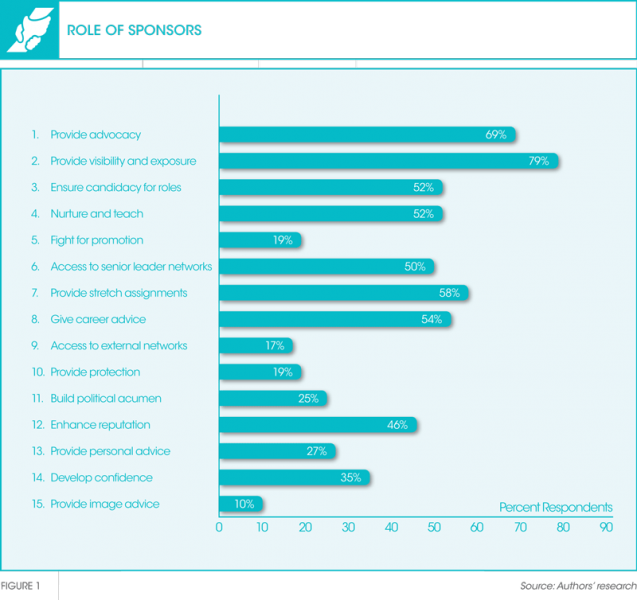

Our in-depth qualitative study reveals that sponsors can aid their charges in up to 15 ways. The things that sponsors do are wide-ranging, from giving visibility and exposure, to nurturing and teaching leadership, and developing traits of executive presence such as confidence and image. They often provide the air cover to enable their young rising talent to have the confidence and safety to try new things.

While having a sponsor can help at any career stage, the importance of having one or more sponsors increases as one rises in the organisational hierarchy and the competition for a few top jobs becomes more intense. In the words of one of the sponsors we talked to, “A quarterback looks exactly like another quarterback physically, as they all may be the same size”. How a person gets noticed is when a sponsor starts talking about him or her—what they can do differently, uniquely and how the sponsor has personally witnessed, observed or trained that person. This is why sponsorship can be an important step in getting promoted or moving towards a more senior role. In short, having people to back you up makes a difference at senior levels. You want people to talk about you positively; differentiating you from the rest of the good candidates. This is, in large part, how a company’s management seeks consensus and reduces their risk of a wrong appointment.

The results of our research also show that having a sponsor not only helps one get a top job, but in the long run, it accelerates careers by one to three levels in the organisational hierarchy. Interestingly, only slightly more than 50 percent of senior managers (defined as those at the director level and above) were discovered as having sponsors.

Sponsorship comes with risks

There are several arguments as to why sponsorship is a practice still relatively unsubscribed to within organisations. Firstly, there are risks associated with being a sponsor. When a sponsor sticks their neck out for someone, they are attaching their own brand and reputation to that person. In the event something goes wrong, such as underperformance, there is a reputational risk for the sponsor: “If she succeeds, it’s good for her. But if she fails, I will have egg on my face. People are not going to blame her because she is ‘bad’. People are going to blame me for the failure.”

Secondly, misperceptions might arise. Rumours of an affair could circulate, for example, especially when the sponsor relationship is between a senior leader and a younger employee of the opposite gender. Some male sponsors specifically told us that they shy away from sponsoring a younger member of the opposite gender precisely because such a perception could potentially taint their reputation, and consequently put a damper on their own careers.

Then there is the issue of showing favouritism. Sponsoring someone could carry the connotation of being personal and biased, which is why some leaders avoid it. They also do not want to be accused of being discriminatory or be seen to play favourites: “I don’t think managers should play favourites, and the tendency for sponsorship is more likely towards favouritism.”

Additionally, sponsors have to be the right people in the organisation with the right goals and the right tools. A good sponsor should not see their sponsee (the person being sponsored) as a future rival who should be kept down or subservient. The sponsor should also possess the wisdom, organisational scope and power to help develop, guide and challenge the sponsee. One of the most common reasons for a sponsor-sponsee relationship to fail is that the sponsor is not familiar with, or adequately engaged in, the relationship.

Why sponsors sponsor

Nevertheless, there are still many senior leaders who are willing to sponsor. There are a variety of reasons for this. Some will want to pay it forward for other people, just as someone had paid it forward for them. In doing so, they fulfil their own psychological need for feeling good, as well as moving up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to attain some form of self-actualisation.

Other managers sponsor because of empathy. Research has shown that empathy drives people to engage in pro-social behaviours, not because of what it does for other people but what it does for them.6 Empathy also enables the cultivation of deep, powerful and meaningful relationships that fulfil a basic human biological need for social connection.7 And then there are others who sponsor because they see sponsorship as a way of developing talent, or of tapping into resources to get things done.

Getting a sponsor

Given that sponsors play a critical role in giving people their shot at a career break, how do you get one? Our research shows that there is one fundamental action that a potential sponsee could do, that is, demonstrate a strong track record of performance. Fundamentally, a strong performance record is crucial for success because “performance trumps everything in the world of practice”.8 It is also what the potential sponsor might notice in the first place. As one of our respondents aptly said: “You’ve got to show that you can deliver because this is what makes or breaks your career.”

Such a sound track record also provides a ‘safeguard’ against the risk of reputational erosion for the sponsor. In the exact words of one sponsor, “No one wants to sponsor a ‘dud’ because it is a quick way to burn your reputational capital”.

The ‘character of leadership’ is another helpful attribute. This is essentially a compendium of traits such as leadership potential, passion, commitment, enthusiasm, drive and emotional intelligence. These are the traits that contribute to long-term organisational success. Frances Hesselbein, whom BusinessWeek labels as the ‘grande dame of management’, describes the character of leadership as the ability of the leader to behave in a way to show ‘how to be’, rather than ‘how to do it’.9 These leaders often look beyond short-term gains to drive long-term advantage and sustainability for their organisations.

Sponsor-sponsee relations might also emerge from supervisor-employee relations or mentor relations. Here, potential sponsors have an opportunity to observe and assess the potential of the employee before deciding to sponsor them. Thus, those seeking a sponsor should utilise every relationship opportunity to impress.

Finally, another way to obtain a sponsor is to ask for it. Interestingly, our research shows that many male sponsors would not consider sponsoring a person unless they are first asked. This finding is in contrast to that of female sponsors, who would often reach out to people to sponsor them, without them asking for it. So, when seeking a male sponsor, you may need to ask for it. Asking does two things for you: first, it signals to the potential sponsor that you are keen to be sponsored; and second it suggests you trust the senior leader to help you progress.

Framework for sponsorship

Sponsorship is a good way to develop and retain top talent. Managers who establish sponsorship programmes in the workplace reap multiple benefits compared to those in organisations where sponsorship is left to the privileged few who get noticed, or who ask for it. We suggest four key approaches for a successful sponsorship experience.

Firstly, a careful selection and matching process is needed. Even though a list of top talent normally exists in most organisations, it is important that managers exercise scrutiny when matching each of the top talents to a senior leader. Factors like chemistry and attraction are important. As Bryne’s theory of attraction demonstrates, people with similar attitudes experience more rewarding and positive interactions.10 Managers also need to pay attention to organisational needs such as the critical skills needed in the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) world of work.

Secondly, an engagement process needs to be agreed upon to set the rhythm for the sponsor relationship to progress. Factored into the engagement process would be the start and end dates, the mid-point date and the frequency of meetings. Given that it takes time for the relationship to grow, as well as to develop and position the sponsee, we recommend that a sponsor relationship should be set for a minimum period of 12 months.

Thirdly, metrics need to be established to measure progress. As Peter Drucker rightly pointed out, “what gets measured gets managed”.11 While metrics measure progress and outcomes, they also drive accountability and commitment to the programme.

And lastly, strong support from the executive team is needed to ensure the programme continues to thrive.