How to make your brand priceless?

What do Tesla, Nescafé, Patagonia, Cirque du Soleil and Red Bull have in common? They form part of a new breed of modern prestige brands that we call Ueber-Brands—brands that are valued beyond their price and esteemed beyond their size. These brands are unique in that they have captured not just the wallet but also the hearts of a huge, loyal and growing customer base. More than offering the usual benefits of their respective categories, they engage with their customers at a different level and beyond considerations of utility and functionality. Some of these brands may start out small, but even Red Bull, priced at around $2-4 per can, pulls in some US$4 billion and more in sales or equivalent each year, as high or higher than any single SKU1 that the mass market majors are selling globally.

‘Prestige’ is a concept as old as mankind and many luxury brands have been associated with it. A Ferrari is not just a car that gets you from point A to B, and a Gucci purse is not just bag to carry things around. Such brands are able to make you

forget about functionality and price (to some extent) and charge prices that are way above the category average.2 Like traditional luxury brands, Ueber-Brands also rank very high in their respective categories in terms of recognition and price; but it is their behaviour and the ways in which they achieve these stellar positions that sets them apart from traditional luxury brands. They slowly yet surely redefine ‘prestige’, by taking into account a much broader perspective.

This article explains how Ueber-Brands depart from traditional prestige brands and create a powerful presence not by pricing up and celebrating themselves as rarefied, but more by evoking pride and aspiration through esteemed ideals and ideas. These brands create a longing not just by building exclusivity through extreme restraint and scarcity (think Hermes’ Birkin bag), but by mixing into these a dose of inclusivity, astutely balancing exclusion with connection. And finally, Ueber-Brands are more truth-minded; they live their mission and radiate their ideals.

The must of mission: Ideas and ideals

Since World War II, businesses have thrived on pushing products to customers who bought more than they needed and spent more than they could afford. The 2008 global financial crisis and the recession that followed changed some of that. Today, there is a growing trend among western consumers to buy not just to own and accumulate, but to buy into a cause.

That is not to say the urge to do good did not exist in consumers prior to the crisis. When Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield first set up their ‘scoop shop’ in Vermont, United States, in 1978, their aim was to sell ice cream and heal the society at the same time. Ben & Jerry’s started off by supporting poor farmers in Vermont and since then, the brand has focused its campaigns on environmental awareness and social and economic equity. The brand developed a huge following.

When Unilever bought the company in 2000 and deprioritised its social activities, sales stagnated. It became clear that customers used to flock to Ben & Jerry’s for more than just its wacky flavours. Consequently, Unilever established an independent board of directors with a separate budget for Ben & Jerry’s, which focused on the company’s social mission and brand integrity–and its customers. Since then, Ben & Jerry’s has flourished despite being associated with controversial topics like “Yes Pecan!” that supported Barack Obama’s election campaign or “Hubby Hubby” that upheld gay marriage rights.

A similar story emerges from TOMS, a California- based company that started off making canvas shoes in Argentina with a one-for-one promise—for every pair of canvas shoes sold, one pair of shoes was donated to the poor children of Argentina. The plain shoes were sold at a steep price of US$59 a pair, but there were enough people who wanted to buy it because they knew their money was going towards a good cause. Over the years, TOMS has expanded into one-for-one spectacles that provide ophthalmic treatment to the needy, one-for-one coffee where each cup sold provides clean water to the poor, and one-for-one bags that help save lives of birthing mothers and their newborns in developing countries.

Customers of Patagonia, the American clothing retailer, are lured by the company’s mission to conserve the environment and its honest commitment to the cause. Every product on the Patagonia website has an ‘ingredient statement’ describing the percentage of recycled materials used, and from where and how the materials have been sourced. The company also publishes The Footprint Chronicles, providing customers with honest information about its supply chain in terms of carbon footprint, Fair Trade practices and the protection of migrant workers.

Patagonia ran an ‘anti’ Black Friday campaign in 2013 dissuading customers from excessive buying–in fact, actively discouraging them from buying Patagonia’s own fleece, jackets and parkas. A full-page advertisement appeared in The New York Times that said “Don’t buy this jacket”. Instead, the company persuaded customers to buy a US$29.99 sewing kit to repair any clothes that may be coming apart at the seams. The company even offered to take back old gear from its customers and sell it on eBay on their behalf.

Patagonia’s products are expensive. A simple trucker hat that typically costs 40 cents to manufacture and is usually sold for anywhere between US$5 and US$15, is sold for US$29 on the Patagonia’s website—and it is sold out—because part of the proceeds are donated to breaking down obsolete dams, freeing the rivers and giving a new lease of life to the wildlife that resides in them. Its consumers don’t feel exploited. Instead, they feel they are part of a movement and are donating for a cause—this is the power of Ueber-Brands.

A principle is only one if it costs you. And Ueber- Brands face this truth time and again. Having an opinion about which political party you support might not sell your ice cream, but Ueber-Brands are willing to take the risk because they believe in the cause. Method, the cleaning supplies company, initiated a campaign to clean up plastic garbage floating in the Pacific Ocean and on the beaches of Hawaii. These plastic bags, fished from the ocean, are used to make hand-soap bottles. Each of these is unlikely to be an immediate pay-out proposition. But in totality, they contribute to the brand’s distinct image and desirability and pay dividends over the long term.

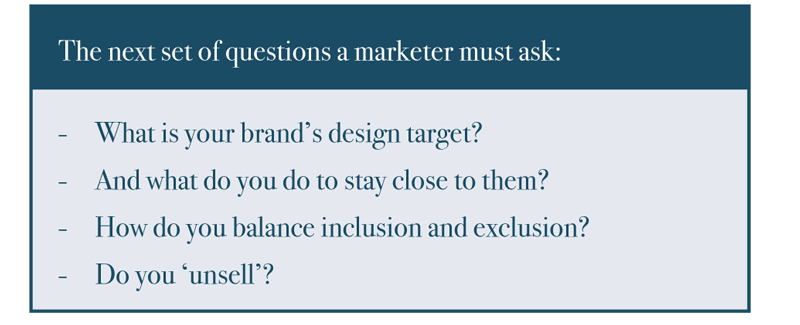

Balancing inclusion and exclusion: Longing and belonging

One of the key objectives of mass marketing is reaching as many people as possible to win the biggest number of customers. At the other end, luxury brands have always been about exclusivity, mostly attained through high prices and limited availability. Today’s Ueber-Brands are able to work out a balance between inclusivity and exclusivity by giving customers a sense of belonging while still keeping them longing. These brands connect their fans into a single community, yet on different levels, with an inner sanctum for their Ueber-Targets, i.e. those consumers who epitomise the brand’s ideals.

For example, the Ueber-Target of M.A.C cosmetics is professional makeup artists. The brand targets them as a professional community through specialised workshops and shows and has created strong ties with them as a cultural cohort through its decade-old engagement in fighting HIV/AIDS. The disease ravaged the heavily gay community of makeup artists, as well as core fashion model and transgender customer groups in the 1990s, and remains an emotional cause that they rally around. he ‘Viva Glam’ lipstick and regular, colourful re-launches with celebrities like Arianna Grande, Nikki Minaj, Elton John or Lady Gaga serve as a link between this Ueber-Target and the broad strategic target of modern cosmetics users. All of the proceeds go towards supporting the M.A.C AIDS Fund, and the M.A.C Ueber-Target rallies enthusiastically behind the initiative every year. To the regular consumer, knowing the money goes to a good cause might just be another reason why buying the product feels right—beyond being ‘limited edition’ and hip.

For another illustration, look at Red Bull. Although the concept of energy drinks has existed since the 1930s, and there are many such drinks currently in the market, no company has achieved the status of Red Bull. Its design targets are extreme sports athletes, stuntmen, race pilots, rock stars and the like–people who play hard and party hard. These people play a central role in all Red Bull events, its main form of advertising, which serve to seduce a broader strategic target, i.e. students, truck drivers and drowsy professionals. Red Bull has mastered the art of having a few influencers ‘in’ on the heroes’ challenge with many more left to admire, desire and dream from the sidelines. Today, the Red Bull can is as iconic as the Coke bottle, except that for 30 years, people have paid three to four times more per ounce for Red Bull than for Coca-Cola.

Harley Davidson follows a similar pattern of marketing. The quintessential Harley rider—the design target—is an outlaw, a rugged libertarian who plays with the boundaries of society and law. The company has built upon the fascination of men with groups like the Hells Angels, the rebellious, independent, dominating American. Yet Harley’s strategic target (the typical buyer) is the suburban, professional, family guy who can afford a bike that costs US$20,000 or more, but can ride it and live the outlaw dream only on weekends.

Carmaker Tesla uses a slightly different, top-down strategy to maintain the allure of its brand while reaching out to the wider target audience. In August 2006, CEO Elon Musk had blogged about his company’s ‘secret’ master plan, “Build sports cars. Use the money to build an affordable car. Use that money to build an even more affordable car. While doing above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options.”3 So Tesla started by launching the Tesla Roadster in 2008, a high-performance super sports car for the rich, eco-tech savvy customers, and then followed it in 2012 with the Tesla Model S, a fully electric luxury sedan. By following such a simple yet clear cascading model, Tesla has been able to effectively balance inclusivity and exclusivity.

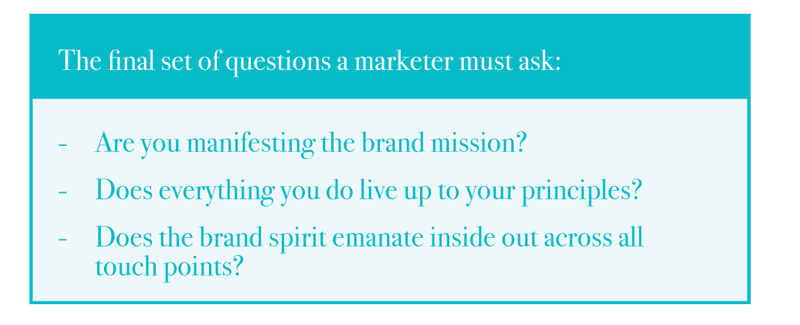

The need for truth: Be the change you wish to see

A final dimension of Ueber-Brands is honesty and truth. Ueber-Brands live their mission and they radiate their ideals, inside out—Patagonia being a case in point. Today’s digitally connected customer is quick to detect lapses in ethics or deficiencies, and paying lip service no longer appeases the well informed. Customers are looking for style combined with substance, and are willing to pay for it.

Freitag, the Swiss brand that makes messenger bags from recycled materials, is a great example of a company that lives up to the promise of its brand. Its story started in 1993 when two brothers, who had studied design, were looking for sturdy, waterproof bags for their bicycle commute in Zurich. Inspired by passing trucks with colourful covers, they constructed a bag from old truck tarpaulin with a piece of seat belt as a strap. Their bag was a hit among fellow students and bike messengers, and eventually spread to individualistic and environmentally conscious consumers. In 2013 alone, the company recycled 400 metric tonnes of tarpaulin into over 400,000 bags and accessories. Freitag’s basic shoulder bag retails for around US$40-60 in Europe, but special edition bags can cost up to US$200 or more, especially when sold outside the continent.

The important point: Freitag’s mission of green living is not just limited to the product it sells, but is consistent and true to its principles from the store and right up to the founders and the factory. The company’s flagship store—where the brothers originally got their inspiration—still stands on the busy intersection of a railway crossing and is made up of 19 rusty steel shipping containers stacked one on top of the other. The factory uses rainwater collected on rooftops to wash the tarp. The owners even now ride their bikes to work and hang out with young employees and customers. The company’s employees all share challenging social backgrounds (many are refugees or high school dropouts) as well as a passion for what the company stands for. Ueber-Brands often don’t need to recruit their employees or sell to their customers; they can choose groups of soul mates and disciples who long to join.

Yuan soap is a small but exponentially growing Taiwanese brand that has taken inspiration from Traditional Chinese Medicine. The company was started in 2005 by a former marketing executive, Ah Yuan, who studied the healing properties of herbs for stress and stress-related ailments and began to make all-natural household and healthcare products from homegrown herbs. The traditional 18-step process to make soap, which takes two months, is followed even today for every piece of soap sold. The Yuan brand truly lives up to its ideals. The strength of the brand is witnessed by the fact that the company experienced double-digit growth even during the financial crisis.

What can Ueber-Brands teach us?

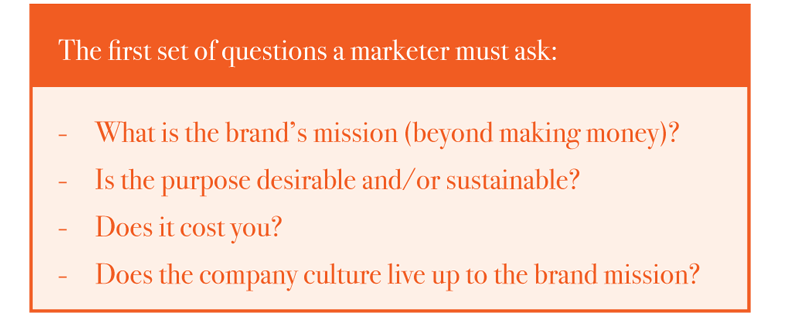

Like all brands, Ueber-Brands too will change and evolve. Besides, the context itself is in flux–how we define prestige in the coming decades will change, as will the ways we experience it. Nonetheless, based on our experience and countless expert interviews and case studies, we find some common principles that have led to the success of Ueber- Brands—versatile principles and techniques that can be helpful to learn the language of prestige in a modern, ‘Ueber-Successful’ way. We think of these as a ‘to consider’ list for those marketers and brand managers who are looking to Ueberise their brand:

• Mission incomparable: Ueber-Brands project a sense of purpose, vision and mission, beyond making money.

• Longing versus belonging: Ueber-Brands walk a fine line between accessibility and exclusivity, proximity and distance. They give their customers a feeling of belonging while making them long for more.

• Un-selling: Ueber-Brands don’t sell, they seduce. They communicate and connect with their targets without ever seeming too eager or needy.

• From myth to meaning: Ueber-Brands don’t just tell a compelling story, they elevate the story to a goal, answering to a higher truth or goal with social value.

• Behold!: Ueber-Brands put their product or service at the centre of attention and make it unique, substantial and superior enough to manifest and support its ideals and mission.

• Living the dream: Ueber-Brands reflect what they believe in, inside out.

• Growth without end: Ueber-Brands are able to grow constantly without over-saturating and undermining their pricing power.