Boosting creativity and innovation in family firms.

When we think about innovative businesses, the likes of Apple and Google typically come to mind. However, the vast majority of businesses worldwide are family-run, and this is especially true in developing regions such as Southeast Asia, where formal business frameworks may be lacking. As the main players in the business environment in these countries, family firms are also responsible for many of the innovations here. When family firms are able to devote resources to innovation, they are more likely to enjoy better performance, competitiveness, and growth.

Important as innovation may be, family firms often fail to leverage the full range of resources at their disposal to be more innovative. I believe that paying attention to an important yet overlooked aspect of family businesses—the underutilisation of non-family employees in creative and strategic processes—and thinking of family firms as an intimate ‘hive’ can provide insights into how family firms can maximise performance and remain competitive.

About 80 percent of people working in family firms are non-family members, and these hired professionals and talents are a potential wellspring of creative ideas. However, family firms often practise nepotism and lack transparency, creating a barrier that prevents professionals from gaining access to critical information and resources that may enhance the quality of their contributions. At best, in-group cliques may sometimes include a select few non-family professionals, but all in all, these obstacles hinder capable professionals from contributing creative ideas to the strategic process, especially if they are excluded from inner circles. As innovation occurs through the successful implementation of novel and useful ideas, family firms are likely to be more innovative when non-family professionals can be engaged to generate creative and impactful ideas. It is therefore imperative that family firms know how to tap into this available but often underutilised resource.

Affective trust is key for family firms

Because individuals in organisations such as family firms are highly interdependent, interpersonal trust is important for workplace cooperation and collaboration to occur. Trust refers to one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another person, despite uncertainties regarding their motives and behaviours. Psychological studies reveal two types of trust: cognitive trust in a person is based on confidence in his or her ability to get tasks done (e.g., their competence and reliability), while affective trust develops when parties form deep relational and emotional bonds with one another. Both types of trust are crucial for organisations to coordinate and perform well.

Cognitive trust tends to precede affective trust in non-family firms. That is, a trustor1 has to find the trustee2 reliable before making more risky social emotional investments in the latter. Family firms are the opposite. By nature, families are characterised by high levels of affective trust due to kinship familiarity, emotional bonds, shared values, common history, and extended periods of interaction among family members. Indeed, family members are often willing to commit and sacrifice themselves for the sake of the family’s welfare without any questions asked. As the family aspect of the business causes relationships and emotions to play a huge role in interpersonal dynamics, the existence of affective trust is a prerequisite for gaining cognitive trust in family firms. Not only does affective trust afford non-family professionals more opportunities to demonstrate their capabilities to the family firm, it can also help weave non-family professionals into the intimate web of familial relations from which privileged information and cognitive trust may be gained.

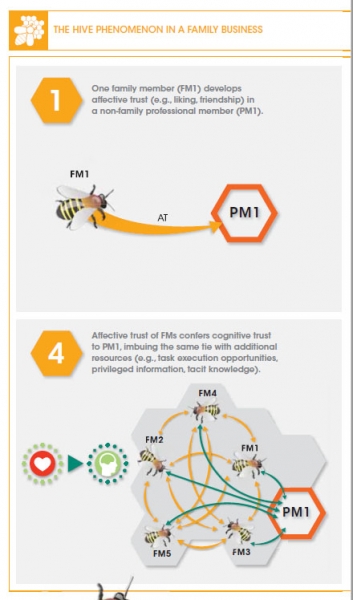

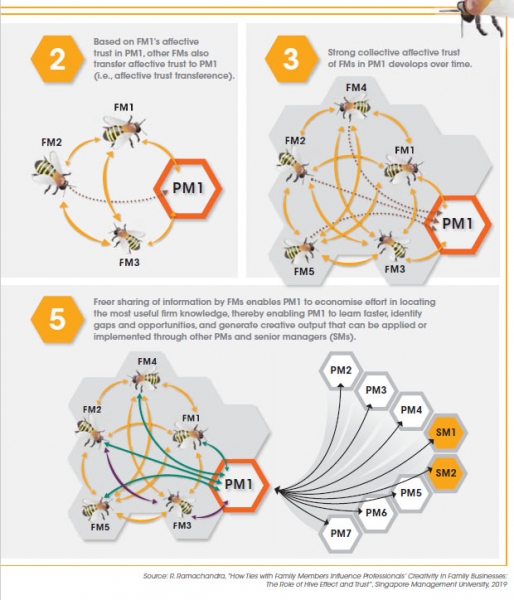

The ‘hive effect’

Our research on family firms in Myanmar revealed that closer ties with family members increased the sharing of knowledge that is critical for creative performance by non-family professionals, which in turn contributed to firm performance and innovation. Noting parallels between this phenomenon and the swarm intelligence of bees that makes them capable of highly efficient collective action, we termed this the ‘hive effect’. When a non-family professional’s network included more family members, he or she was regarded as more trustworthy by the entire family through a process of trust transference among family members. That is, family members can trust the non-family professional if this person has gained the trust of other family members. Thus, first-hand verification is not required in a family ‘hive’ where affective trust is the main currency, and family members can develop affective trust in non-family professionals without having established direct contact. As a result of this ‘hive effect’, non-family professionals can enjoy exponential growth in affective trust despite not having befriended everyone in the family.

High levels of affective trust lead to an increased transfer of cognitive trust, opening up a tremendous snowballing of benefits. Our research showed that as a non-family professional becomes more and more liked in a family-run organisation, there will be greater willingness to entrust the person with important tasks (which, if successfully performed, increases perceived competence and reliability), as well as critical information to facilitate task execution. Reflecting on this, one senior family member told us, “It is like a three-step process. When you hire someone, you of course think that they probably can do the job. But then you have to watch them to see if they can get the small things right, such as whether they are sincere and have a good attitude, or whether they demonstrate ownership and can contribute to the collective family spirit. Then you trust them more, after which you can give them more important duties to perform.” Another similarly remarked, “I give a trusted subordinate more access to information, knowledge, and resources compared to others that I trust less.” Non-family professionals who receive this trust are well aware of the preferential treatment they are afforded. One middle-level purchasing professional said, “I was given more jobs even though there is a senior person above me. They gave me more responsibility and information on whom I can trust and whom I should not.”

Thus, in addition to liking and friendship, ties grow thicker with access to additional resources, such as information and know-how through cognitive trust. This expansion of cognitive trust and knowledge allows non-family professionals to economise their efforts in locating the most relevant and idiosyncratic knowledge in the family firm, which in turn enhances their learning and alertness to gaps and opportunities. As trust grows, family members also relax their oversight and grant trusted non-family professionals greater autonomy, thereby freeing up company resources for more effective exploitation by non-family professionals to generate creative outputs. In sum, transaction costs are lowered while value creation is raised through trust that not only exists among family members, but is also extended to non-family professionals.

Creativity and innovation via the ‘hive effect’

Family firms that know how to leverage the ‘hive effect’ gain a formidable means to outperform rival businesses. Being unique to family firms, the ‘hive effect’ also confers on them a distinct competitive advantage over non-family firms. professionals, and by doing so, family firms will have more of the basic ingredients that underlie innovation.

Our research on family firms in Myanmar found that non-family professionals exhibited significantly greater creativity as the number of family members in their ‘hive’ network grew. As trust correspondingly increased with each additional family member in the network, non-family professionals found themselves embedded within an environment that was more and more conducive to creativity, and thus became more motivated to produce impactful ideas. These observations are consistent with the current research literature on creativity, which stresses on the importance of not only individual motivation, but also supervisor empowerment and a supportive organisational environment. As non-family professionals gained access to important information and resources that would otherwise be obscured due to the idiosyncrasies of family firms, they were able to better grasp the strengths and weaknesses of the firm, and propose useful ideas that contributed to innovation. In addition, non-family professionals who had the trust of family members felt more confident about expressing their views. One such professional said, “I can speak up and share my opinions without worrying that I’m stepping out of line.”

The implementation of creative ideas also requires a unique set of capabilities, such as the ability to lobby the right individuals for the relevant means and resources to launch ideas. Family members holding important positions in the company can be valuable sponsors or champions of the strategies developed by non-family professionals. As one family member put it, “When I trust non-family employees, I will give them lots of resources and extra support. Sometimes, if they get stuck with small things that are crucial for them to succeed, I will try to help them resolve the difficulties, so that they can fulfil their potential.” A non-family professional added, “Although a senior family member put pressure on the entire team to meet targets, I can see that I’m trusted as my proposals are accepted with few amendments and carried out more readily. In comparison, he does not accept the proposals of others as easily.” As such, the support of such key family members can be vital to transforming suggestions from mere ideas to actual roll-outs.

How can family firms leverage the ‘hive effect’?

Now that we have discussed the creative benefits that can be derived from trust through the ‘hive effect’ of family firms, this begs the question: what steps can family firms, managers, and business practitioners take to harness the ‘hive effect’? I recommend the following strategies.

INTEGRATE NON-FAMILY PROFESSIONALS INTO THE FAMILY CULTURE

A clear and straightforward approach to increasing trust between non-family professionals and family members is to embed the non-family professionals actively into the family dynamic. For instance, senior family members with key roles in the firm can increasingly involve promising non-family professionals in a gradual manner, starting first with more informal family conversations and gatherings, before progressing onto more serious meetings about the strategic direction for the business. As one family member said in an interview, “About 95 percent of our conversations with professionals are friendship-based discussions in family or social gatherings.” As relations become more intimate, non-family professionals can be entrusted with privileged information and bigger tasks.

Senior non-family professionals who are already part of the family in-group can also help to co-opt new professionals and champion those who are particularly effective and capable. However, our observations of family firms in Myanmar revealed that affective trust from non-family senior managers produced less cognitive trust compared to affective trust from family members. That is, for the same amount of affective trust in junior professionals, non- family seniors gave relatively less resources, such as career guidance, information, and access to networks, compared to family members. As family members have less to prove in the firm, they are much less reluctant to give cognitive trust and associated resources to non-family professionals once affective trust is established. Thus, for this recommendation to work, senior non-family professionals must downplay their competitiveness and be willing to not only acknowledge the work of junior professionals, but also share valuable resources.

Onboarding processes for new talents and professionals can also be tweaked to improve integration into the family business and culture. The need to get up to speed quickly with family traditions and practices is especially important in Asia, where family values and collectivism play a huge role in social and business dynamics. To facilitate a better understanding of family expectations, a transparent checklist of how to not only be successful in the company but also become part of the family culture can be drawn up for new hires. For example, upon joining Tan Hiep Phat (THP), a family-owned beverage manufacturer in Vietnam, employees are given a handbook containing information about the company’s history, vision, and practices, as well as the expectations that employees must live up to in order to become a member of the THP family, such as respecting customers and serving the community. THP explicitly states in its handbook: “The emphasis on family is critical. We consider the society in which we operate as an extension of our family. We believe that it is critical for everyone at THP to make a sustainable contribution to the communities in which we operate.”

Beyond grand statements about company expectations, we also suggest that it may not hurt to spell out even the basic minutiae of everyday family life. What is a common practice to a family may not be so for those who are unfamiliar with the family culture, which could result in unnecessary friction. For instance, it is a faux pas in Asia not to remove one’s shoes before entering a house. Because of the grey lines between the home and the workplace in family firms, employees sometimes walk into the business founder’s office with their shoes on without realising that the office is in fact also part of the family residence. Thus, a list of simple family expectations and practices could go a long way in preventing needless misunderstandings.

IMMERSE FAMILY MEMBERS IN DIFFERENT ROLES AND TASKFORCES

Conversely, family members can be encouraged to interact more with non-family professionals in different settings across the business. In our observations of family firms, we found that family members preferred to associate with people they were already familiar with and avoided venturing beyond their own cliques. This tendency fosters an in-group-versus-out-group environment, thus hampering the formation of trust and productive linkages between non-family professionals and family members.

One way to encourage greater intermingling is to incorporate departmental or functional role rotations into the business ecosystem. A fair bit of success was observed when this approach was adopted by the family-owned, engineering-centric Baron’s Group and its subsidiaries in Myanmar. However, instead of moving people around randomly, network analysis can be used to determine areas in the firm where non- family professionals are less creative, so that key family members or senior professionals can be transferred there to spur creativity. Although our research showed that well-liked non-family professionals did not have to interact directly with family members to be given trust, departmental units without a strong family member presence have limited opportunities for trust transference, especially since family members are usually a small minority in the firm. Hence, these rotations will enable family members to meet more people outside their own circles and increase the likelihood that trust will be transferred to non-family members.

Lastly, onboarding processes can be structured such that newcomers have opportunities to meet family members informally, thereby increasing interactions in a non-work context that help build affective trust. Activities ranging from weekend family outings to team-building exercises may go some way towards developing intimacy and fostering stronger bonds.

INVOLVE NON-FAMILY PROFESSIONALS IN CREATING A SHARED VISION

Family members and non-family professionals can establish a common understanding and develop shared responsibility for the future by co-creating a vision or strategy for the family firm. The organic processes of such an activity allow participants to interact, communicate, and build trust (particularly affective trust) outside the usual office environment. Non-family professionals would also be able to see the aims and aspirations of the family members more clearly, and experience greater buy-in of the company’s goals.

In addition, non-family professionals can learn about what is important for the family firm from these sessions, and use this understanding to build their own credibility, for example, by knowing how to do their part to help the company work towards its goals, and thus be successful themselves in the company. For instance, a medium-sized family- owned business in Thailand that specialises in food ingredients conducted its visioning process and invited some new professionals to take part in shaping the company’s future. Two out of three senior professionals who were new to the firm actively participated in the process. Consequently, they were able to integrate seamlessly into the family culture and make informal contact with family members as they were perceived as demonstrating a strong interest in the company. This proved to be an advantage later as they could access idiosyncratic information and resources, whereas the third person who did not actively participate in the process missed the opportunity and eventually became less effective at work.

CREATE FORMALISED SUGGESTION SCHEMES

Feedback and suggestion schemes can also be established to involve non-family professionals further in shaping the direction of the company. In the case of Barons & Fujikura EPC Co., Ltd. (BFE), a subsidiary of the Barons Group engaged in the engineering, procurement, and construction industry in Myanmar, a suggestion scheme was implemented to allow non-family professionals to provide strategic ideas. BFE received about 360 suggestions from a ‘creativity test’ to derive suggestions to save costs, after which it quickly shortlisted 10 of the best ideas and gave a small monetary prize for the top five. Most importantly, the company saw value in these ideas and implemented three out of the five best ideas. To be sure, many firms do have suggestion schemes, but they lose steam over time if management does not take action and demonstrate that it cares about the feedback provided. However, because family firms tend to have less formalised decision-making and bureaucratic structures, they have the advantage of being able to implement these ideas more quickly.

PROMOTE HARMONY IN THE FAMILY AND REDUCE SOURCES OF CONFLICT

How well the ‘hive effect’ works depends on the state of relations among family members. More specifically, when conflict among family members is minimal, the ‘hive effect’ has the greatest positive impact on creativity. Disunity among family members can spill over to non-family professionals who end up having to take sides, causing them to be distracted from more constructive pursuits in the firm. The negative long-term consequences of failure to ensure harmony cannot be overstated. As such, family firms should get their ownership and functional roles sorted out, and be mindful about how family issues can complicate the business. Only when there is an aligned future for the family unit, would it be possible to work with the management on its performance culture, and hence it is important that the family unit first resolve any possible conflicts with regard to roles, processes, tasks, and relationships.

Conclusion

Rather than something akin to complex rocket science, innovation emerges most simply from the integration of creative ideas into useful solutions that can be effectively implemented. When non-family professionals, who form the majority of employees in family firms, are empowered with trust, they are more likely to acquire the resources needed to generate creative ideas and contribute to innovation.

Thus, family firms can become a hotbed of creativity if they can harness the ‘hive effect’, a phenomenon that can propel them to new innovative heights and afford them a unique competitive advantage over non-family businesses.

Dr Rameshwari Ramachandra

is Managing Director of Talent Leadership Crucible Pte Ltd (TLC)

This article is derived from the author’s doctoral dissertation, dissertation entitled “How Ties with Family Members Influence Professionals’ Creativity in Family Businesses: The Role of Hive Effect and Trust”, Singapore Management University, 2019.

Endnotes

1. In this context, it refers to a family member who is putting his or her trust in a non-family employee.

2. Here, the word refers to a non-family employee who gains the trust of a family member.