In 2015, among a sample of 130 countries, Singapore ranked a s the tenth most entrepreneurial, based on an aggregate index accounting for entrepreneurial attitude, ability and aspiration.1 The island state was also noted to be the second most competitive country for business globally, and has retained the number two position worldwide for having the best intellectual property (IP) protection four years in a row.2

Starting from the bare basics where most entrepreneurs were non-Singaporeans, the country’s entrepreneurship landscape has blossomed over the last decade. Business entities formed in Singapore rose from 41,713 in 2004/2005 to 62,229 in 2013/2014.3 Although exact numbers are not readily available, industry experts believe that employment at these young start-ups has risen by about 80 percent during the same period.4

This progress is the result of sustained efforts by the government to develop a conducive environment and a robust ecosystem that caters to the needs of entrepreneurs. But what is it that Singapore is doing right? And what more needs to be done in order for it to further climb the ranks, and become Asia’s nucleus for thriving entrepreneurship?

In 2015, Singapore ranked as the tenth most entrepreneurial country among a sample of 130 countries.

Key enablers—building Singapore’s entrepreneur ‘ship’

As a young and fast-growing economy, Singapore has a healthy cluster of motivated entrepreneurs with solid education, savvy business skills and a plethora of good business ideas. And the momentum is building, as many more Singaporeans are willing to try entrepreneurship as a career option. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of start-ups are in the technology sector, though Singaporeans have applied technological innovations to an array of industries, such as retail, finance, food and beverage, hospitality, talent management and even social enterprises.

With a booming financial sector, Singapore is also fortunate to have a large number of cash-rich investors looking for lucrative investment opportunities. These range from angel investors and venture capitalists to corporates looking to support the development and commercialisation of new inventions or business propositions.

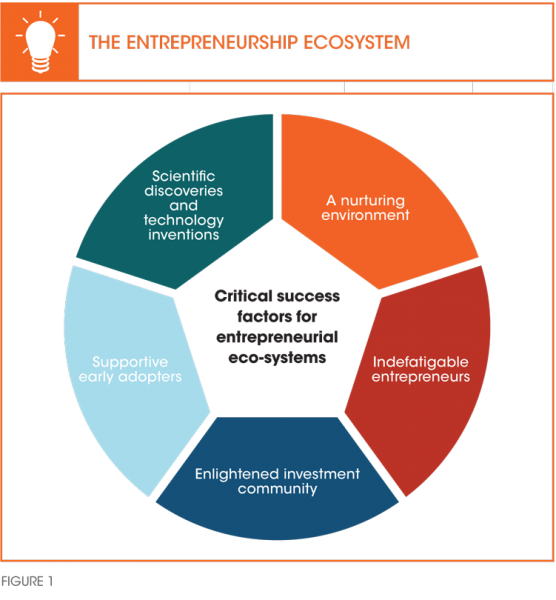

However, the recipe for Singapore’s entrepreneurial success so far has needed more than just entrepreneurs with good ideas and investors with money. It has come about because of the proactive role of the government to create and develop a supportive ecosystem in which the island’s entrepreneurial capabilities could develop and flourish. The government has undoubtedly been the key enabling institution in developing the entrepreneurship sector in Singapore. Through efforts on multiple fronts, a nascent ecosystem has developed leading to the robust growth of start-ups (refer to Figure 1).

|

ENTREPRENEURSHIP VERSUS SMALL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT The word ‘entrepreneur’ is sometimes used to denote a person who runs a small business. However, there are important differences between building a small business and entrepreneurship. A small business, such as a café, is a well-known type of business. In starting such a business, the main challenge the owner has to face is the business risk. Business risk refers to factors such as adequate capitalisation, business location, operational and marketing costs, and hiring the right people. An entrepreneur has to manage two additional risks—market risk and technology risk. Market risk refers to the customer discovery phase or product market fit. Entrepreneurs offer new value, or deliver value through new channels, to their customers, and so they have to manage the risk of identifying or predicting the correct target customers and the right price point at which they would be willing to buy the product or service being offered. The second additional risk is the technology risk. Entrepreneurs often build their solutions using new technologies, which perhaps have never been used before. There is always the possibility that the chosen technology may not help implement the proposed solution satisfactorily. These major differences between small business development and entrepreneurship are often overlooked. |

The government has undoubtedly been the key enabling institution in developing the entrepreneurship sector in Singapore.

The proactive role of the government

REGULATORY INCENTIVES

The Singapore government has supported entrepreneurship by creating a favourable regulatory environment. Over the years, the government has provided substantial indirect support to angel investors and entrepreneurs through tax benefits. Entrepreneurs can qualify for the Productivity and Innovation tax credit, R&D Expenditure tax credit and a Tax Deferral option. There is also an Angel Investors Tax Deduction Scheme under which 50 percent of the investment in a Singapore-based start-up is eligible for tax relief. To incentivise risk-taking, bankruptcy laws were revised in 2013 to give relief to young companies trying to build credibility in the market.

R&D SUPPORT

The government has purposefully fostered a supportive environment for scientific discoveries and technological inventions. Four Science & Technology (S&T) five-year plans have been implemented between 1991 and 2010. During this time, the total R&D expenditure has increased almost tenfold, from US$760 million in 1991 to US$6.04 billion in 2009.5 These efforts have brought about positive results, and Singapore has developed a unique spectrum of deep capabilities across the fields of biomedical sciences, physical sciences and engineering, and created a robust knowledge-based economy. In a 2013 ranking of more than 200 countries, Singapore was the seventh most innovative country in the world, based on factors such as R&D expenditure, percentage of public high-tech companies and patent activity.6

SEED FUNDING

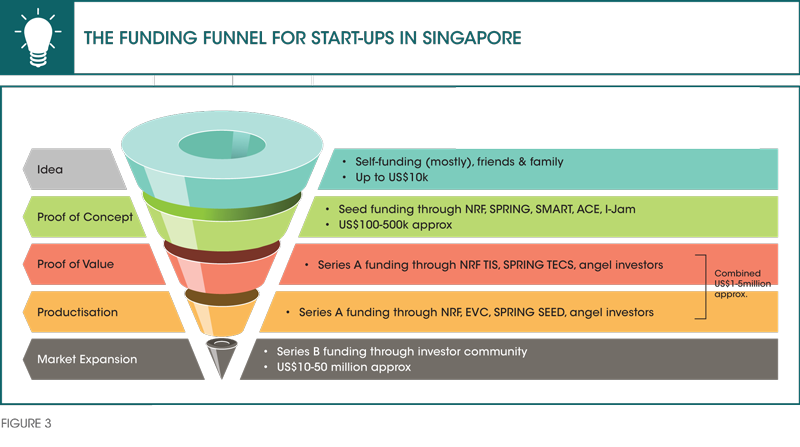

The Ministry of Trade and Industry has also been proactive in creating multiple channels through which start-ups can access funding, recognising a gap between the demand and supply of seed funding. In addition, there are many incubators where start-ups can experiment and develop new technologies.

COMMERCIALISATION

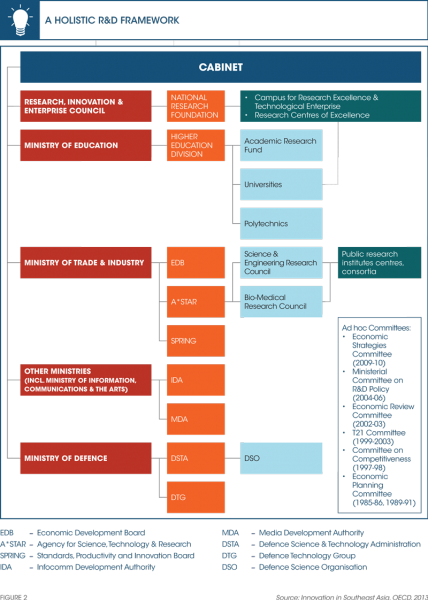

The translation of research into commercial use is a process systematically engineered by government and public sector agencies to create a vibrant innovation value chain. Agencies such as the Economic Development Board (EDB), SPRING Singapore, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) administer programmes and funding schemes to provide support throughout the innovation value chain, from basic research to applied and translational research, through to commercialisation. A holistic R&D framework ensures the long-term relevance of Singapore’s R&D investments (refer to Figure 2).

Missing parts—developing an entrepreneurial culture

Singapore today possesses many of the elements of a successful entrepreneurial economy. But what will it take to move the entrepreneurship industry to the next level, and make Singapore the innovation and entrepreneurship capital of Asia? I now take up some of the challenges facing Singaporean start-ups today.

SOCIETAL MINDSET

One of the pre-emptive constraints faced by young start-ups in Singapore is the societal perception of seeing entrepreneurship as a risky career in comparison with a salaried job. The first obstacle for an eager entrepreneur starts at home with, “How do I convince my parents?” For the most part, youth are actively discouraged from taking up entrepreneurial activities. Families often find the odds of a start-up’s success unfavourable, and encourage their children to take up ‘secure’ employment.

EARLY ADOPTION

In order to thrive, entrepreneurs need a receptive market. I find that Singaporean customers are hesitant to adopt new products and solutions that have not been tried and tested in other markets. This conservatism and lack of willingness to spend on and experiment with innovative technologies, combined with the small size of the Singapore market, become a serious impediment for start-ups looking to prove the success of their product in their home market before expanding to other countries.

INVESTOR CONSERVATISM

Despite the availability of cash-rich investors, start-ups often struggle to get funding, especially in the early stages of the business. Investors tend to be conservative in terms of valuation and look at a start-up purely in terms of a financial play. They typically prefer to get in the business after the proof of concept stage; or when some risks have already been removed (refer to Figure 3). I know of people who call themselves angel investors but want to pick up a stake in a start-up only after the company has started making profit and is cash positive. To me, they are not angel investors.

I know of people who call themselves angel investors but want to pick up a stake in a start-up only after the company has started making profits and is cash positive. To me, they are not angel investors.

MAVEN INVESTORS

The profile of the investor community in Singapore, and in Asia in general, differs from that of Silicon Valley. In the latter, many investors, or ‘Mavens’7, are ex-entrepreneurs and successful business leaders who have developed deep knowledge and extensive experience in a particular industry. Often wanting to pay forward their successes, these investors can foresee the value of a business idea and their assessment of a start-up goes beyond a simple financial valuation.

These Mavens bring much more than money to the table—they are visionaries and risk managers who use their domain knowledge and Rolodex of contacts to support and guide entrepreneurs right from the idea conception stage. They know whom to call, and they know what works and what doesn’t. They can create significant value for the business, in addition to supplying start-up capital.

SERIAL ENTREPRENEURS

For Singapore to develop a stronger entrepreneurial culture, the business community needs to learn from the previous generation of business leaders. Just like the strength of an economy is measured by the number of times a single dollar is used or churned in a given unit of time, the strength of a nation’s entrepreneurship sector can be judged by how many new start-ups benefit from the ‘entrepreneurial intelligence’ of successful entrepreneurs.

Being relatively new in the game, Singapore lacks a critical mass of successful serial entrepreneurs. Our entrepreneurs think small and sometimes give up easily. There are very few start-ups that have the potential to grow to a US$1 billion business. Over time, I expect successful Singaporean entrepreneurs to invest their knowledge, expertise and experience into helping new business ideas to be crafted into billion dollar businesses, and only then the momentum will catch on.

SERVICE PROVIDERS

In Silicon Valley, a start-up company can find lawyers, accountants and other service providers that will offer their services at a discounted rate (below the market rate) in return for equity in the company. But we don’t have such practices in Singapore. In fact, the rates that service providers quote for start-ups in Singapore are exorbitant, and they seem to ignore that start-ups cannot afford to pay that kind of money. A change in the mind-set of the service providers—instead of focusing on money on the table now, they should place their bets with companies that have good prospects—will accelerate the development of Singapore’s entrepreneurship eco-system.

UNBALANCED RISK PROFILE

From a financial perspective, the Singapore government has been doing a lot of heavy lifting to support entrepreneurship. In many cases, its stake is 85 cents for every dollar, or even a dollar for every dollar of investment, which makes the government the principal risk-taker in the venture. While this is helpful in the early years, a mature entrepreneurial ecosystem can emerge only when the private sector becomes the main player.

Also, when the government has deep financial interests in a start-up, it leads to suspicions about the neutrality of the company, especially when the business expands overseas to our nearest neighbours. In my view, the government can play a big role in the early stages by developing the environment and the ecosystem, but it cannot be a major investor in the country’s entrepreneurship portfolio forever.

In summary, it is fair to say that every nascent entrepreneurship sector needs the support of the government in the initial stages. Singapore has already established a dynamic ecosystem to cultivate and nurture research, innovation and entrepreneurship. It now has to embark on the next steps to change the mindsets of young entrepreneurs (and their parents), the investor community and even service providers.

|

BEYOND SINGAPORE—ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN ASIA Asian countries exhibit a wide diversity in terms of their level of entrepreneurship development. As remarked in the 2015 Global Entrepreneurship Index report, “On the one hand, the region (Asia) includes some of the world’s leading entrepreneurial economies, such as Australia (3rd), Taiwan (8th), and Singapore (10th). On the other hand, it also has global laggards such as Myanmar (109th), Indonesia (120th), Pakistan (123rd), and Bangladesh (at 130th place, it is the bottom performer in the global GEI ranking).”8 The entrepreneurship models also differ—while the government is the key player in Singapore and Malaysia, the private sector has taken the lead in Hong Kong and Indonesia. Asia offers a big, albeit fragmented, market for all types of businesses. In my experience, the overheads in customising solutions for different countries can often be as high as 20 to 30 percent. Indonesia, for example, is a large market and Indonesians are quite active in the world of Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking services. As Indonesia’s economy grows, there will be aspirations from the local population and this will create consumer demand for new products and services. So every entrepreneur, whether in Singapore or elsewhere in Asia, should keep Indonesia on their radar screens. It is not easy to do business there, but they must learn to do business there. Singapore’s open economy and government-supported development of entrepreneurship provide some lessons for other Asian countries that are beginning to embark on this journey. At the political level, a stable, democratic government that is pro-entrepreneurship is the first necessary step. For some countries such as Malaysia and Thailand, this will mean improving the infrastructure and shielding the start-ups from a possible onslaught by industrial conglomerates that currently dominate the business landscape. Developing nations, such as Cambodia, Laos, and Bangladesh, will first require a strengthening of the institutional and regulatory frameworks and then gradually develop entrepreneurial skills through investments in human capital. India has to gradually shift its focus from creating new service-oriented companies to product innovation-oriented start-ups. |

Thinking big

High risk and high reward go hand-in-hand. Every entrepreneur knows that.

Although I believe that Singaporean entrepreneurs are capable of keen ideas and forward-looking business ventures, the absence of a risk-taking investor community and a large, receptive market deters Singaporean entrepreneurs from engaging in or pursuing disruptive innovation and breakthrough technologies. I find that the majority of start-ups work on incremental innovations or on copies of innovative models that have proven to be successful elsewhere. A recent report by KPMG stated, “Invariably, most start-ups struggle to grow and failure rates are extremely high. Although young entrepreneurs may demonstrate ideas, motivation and expertise, they lack experience and capital assets.”9

So far, not many start-ups have shown significant exits through trade sales or initial public offerings (IPOs). The largest exit by a Singapore-based company was by Viki, a video streaming website bought out for US$200 million by Japan’s Ratuken. And although Viki was registered in Singapore, none of its founders were Singaporeans. Other examples include Zopim, a live chat software, which was bought out recently for US$30 million, and prior to that, tenCube, a mobile security firm, that was acquired by McAfee for about US$10 million. But these buyouts are small, and small market size is often mooted as a key structural constraint for Singaporean enterprises.

I recollect one savvy Silicon Valley-based investor saying that he would prefer to invest in a start-up that has a one percent chance of becoming a billion dollar company, as opposed to one that has a 90 percent chance of becoming a 10 million dollar company. From that point of view, Singapore still has some ground to cover.

The absence of a risk-taking investor community and a large, receptive market deters Singaporean entrepreneurs from engaging in or pursuing disruptive innovation and breakthrough technologies.