The street scene of honking cycle rickshaws, jaywalking pedestrians and precariously tilting buses in crowded Dhaka was an easy distraction. It was December 2017 when Matteo Chiampo, an advisor to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP),1 was writing an advisory report on the future growth strategy for SureCash, a mobile financial services (MFS) company in Bangladesh. Brainstorming for questions, and not answers, was something he had not tried before. Nevertheless, Chiampo tried to focus on the questions he had on his mind—questions that he believed would give novel and transformative insights on the way forward.

SureCash was founded in 2014 with the objective of providing a range of mobile financial products to the unbanked population in Bangladesh, and a long-term vision to become the premier ‘digital financial services’ provider in the country. The company tied up with local retail convenience or ‘mudi dokan’ stores and mobile phone shops to deliver financial services to its customers. The initial approach, focused more on mobile services, was based on an agent banking structure. This meant providing limited scale banking and financial services through engaged agents under an agency agreement, rather than a teller/cashier system. SureCash was thus the owner of an outlet which conducted banking transactions on behalf of a bank, and to this end, it had co-branded with five banks, along with establishing collaboration agreements with mobile network operators and other partners.

SureCash was founded in 2014 with the objective of providing a range of mobile financial products to the unbanked population in Bangladesh, and a long-term vision to become the premier ‘digital financial services’ provider in the country. The company tied up with local retail convenience or ‘mudi dokan’ stores and mobile phone shops to deliver financial services to its customers. The initial approach, focused more on mobile services, was based on an agent banking structure. This meant providing limited scale banking and financial services through engaged agents under an agency agreement, rather than a teller/cashier system. SureCash was thus the owner of an outlet which conducted banking transactions on behalf of a bank, and to this end, it had co-branded with five banks, along with establishing collaboration agreements with mobile network operators and other partners.

In early 2017, SureCash created history by transporting the nation’s Primary Education Stipend Project (PESP) onto its digital platform. In the process, it successfully opened accounts for 10 million women in Bangladesh, and transferred the stipend funds to their accounts. However, despite this large deal, CEO Shahadat Khan was on the lookout for new growth opportunities that could be created for his relatively small company.

The MFS sector in Bangladesh was essentially an oligopoly dominated by two large players: bKash, which held more than half of the market share, followed by the Dutch Bangla Bank Limited (DBBL), which owned about one-sixth of the subscribers’ market share, at a distant second. With advice from CGAP, Khan was considering the kind of growth strategy a player like SureCash could implement in such a market.

Homegrown technology

The SureCash software platform had been developed internally, leveraging web-based technologies. As the backend platform was built and controlled by the company, customised development and modification took less time as compared to commercial platforms. The full software development lifecycle, including testing and production maintenance of service solutions, were all done in-house. Being able to control its entire technology stack was a definite advantage for SureCash. Other MFS providers in the country had typically acquired platforms built by third-party foreign companies, who were unlikely to understand the unique needs of the local customer. The SureCash platform was designed to be fast, real-time and reliable, and used the mobile phone as the primary transaction interface.

Opening an account

Opening a SureCash account through one of its partners was a simple process offered free to the customer. Customers could go to any agent outlet in the country with their mobile phone (the mobile operator needed to be a partner of the company), proof of identity, and a photograph, and complete a form. Once the forms were completed and verified, the customer would receive a confirmation SMS that the account had been opened. Thereafter, they could avail of a range of services including cash-in, cash-out, cash transfers between individuals (P2P), cash transfers from business/organisations to individuals (B2P), bill payments, merchant payments, mobile top-ups, and collections.

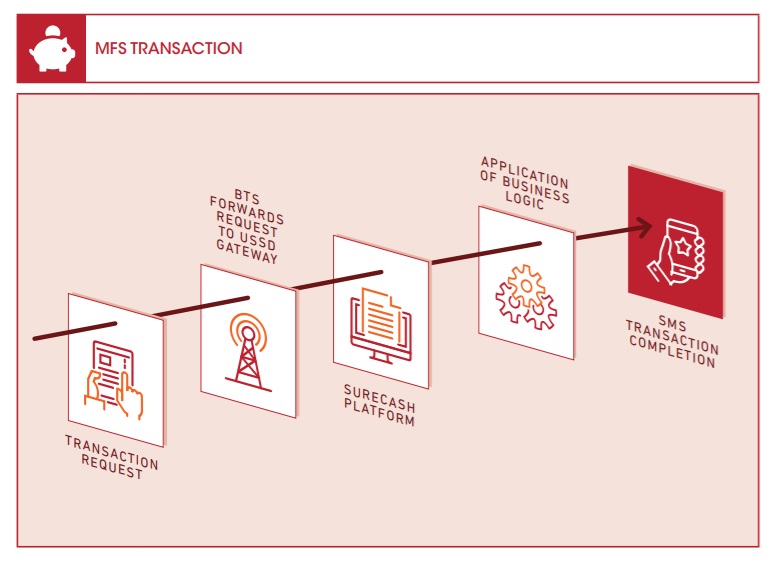

MFS transaction

A typical MFS transaction request from a SureCash customer is placed over Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) through a menu-driven user interface on the customer’s mobile phone. Once the customer initiates the transaction request, the base transceiver station (BTS) of the mobile network operator (MNO) would forward the request message to the USSD gateway. The USSD browser at the MNO would then send this message to the SureCash platform, which would parse the transaction and apply the appropriate business logic for the product, complete the required entries, and send an appropriate response to the transaction initiator over the USSD channel and a transaction completion message over an SMS channel to both parties involved in the transaction.

Over-the-counter transaction

Over-the-counter transaction

For over-the-counter (OTC) wallet-to-wallet remittance, customers had to visit an agent outlet to execute the transaction. They handed over the amount to transfer in cash to the agent, and indicated the recipient’s account number. The agent then performed the transaction on his/her mobile or electronic device. The platform would require a PIN confirmation to ensure security, thereafter, the agent’s wallet was debited, and the recipient’s wallet was credited, after deducting the transaction fee. This transaction flow for wallet-to-wallet remittance was the most frequent transaction performed by MFS customers.

The MFS market in Bangladesh

MFS in Bangladesh had been established as part of the government’s regulatory reforms, which allowed financial service providers to operate in the country in partnership with a locally-registered bank. These reforms were introduced in early 2011, following which DBBL and bKash entered the market almost immediately.

The market conditions at the time had worked to the advantage of the two first movers. Margins on reselling airtime had fallen dramatically in 2012. So when these MFS players entered the market, the mobile airtime reseller outlets jumped at the opportunity of becoming MFS agents, as it provided them some extra revenue from agency fees and also increased customer traffic to their outlets. As a result, the agent network for bKash, which had been launched in partnership with BRAC bank (a private commercial bank in Bangladesh that focused on small and medium enterprises) surged. Within the first two years of operation, bKash was able to gain a significant market share, and by 2015, it had become the clear market leader, with 58 percent share of Bangladesh’s MFS market. By October 2016, it strengthened its position to account for 89 percent of the total MFS transactions in Bangladesh, with DBBL accounting for another 10 percent, and the balance one percent transactions executed by other MFS operators. In terms of transaction value too, bKash was the clear frontrunner, accounting for more than 75 percent of the amount transacted.

Having one or two large dominant players in the market had several drawbacks for smaller MFS players, including bleaker possibilities for building large agent networks, less control on transaction fees, and a challenge for brand management. This was in addition to the risks faced by all MFS operators, which included local agents allowing registration of fake accounts without ensuring proper verification, or then daily operational challenges related to interoperability, where interoperability is defined as ‘the possibility to transfer money between customer accounts at different mobile money schemes, and between accounts at mobile money schemes and accounts at banks’5.

Tackling an oligopolistic market

Rather than competing directly with its competitors, SureCash had chosen to adopt the path of differentiation to make its mark on Bangladesh’s MFS market. In 2014, the company had started working with educational institutions to facilitate the collection of tuition fees, and decided to pursue this path. Most educational institutions in the country were at the time still maintaining piles of physical ledger books to keep track of student fees and payments—which was proving to be increasingly inconvenient.With the adoption of the SureCash digital mobile payment system, the student fee collection process became simpler and more efficient with convenient report generation, tracking and reminders. Some institutions had further customised the automated platform and added solution features to roll out vaccination service initiatives, fingerprint technology for hostel students, and library automation. By 2016, more than 200 educational institutions collected semester and monthly tuition fees using the SureCash educational fee collection platform.

At the same time, SureCash also began promoting its platform to organisations for salary disbursements. Organisations like Grameen Bank (a microfinance organisation and community development bank founded in Bangladesh), Grameen Trust, Integrated Development Foundation, and FoodPanda started disbursing salaries, transport allowances and vendor payments using SureCash’s platform. Some rural banks also began venturing into disbursing loans and collecting payments using SureCash. In 2016, Grameen Bank signed a memorandum of understanding to use the company’s mobile payment platform for its operations. Through this partnership, Grameen Bank members were able to use SureCash mobile banking to receive loans and make instalment payments using their mobile phones. This proved to be a great opportunity to introduce the benefits of MFS to around 8.8 million Grameen Bank members covering 97 percent of villages in Bangladesh. Later that year, some other government agencies, such as the Water Supply and Sewage Authorities and Bangladesh West Zone Power Distribution Boards, began partnering with SureCash to collect utility bill payments from their consumers.

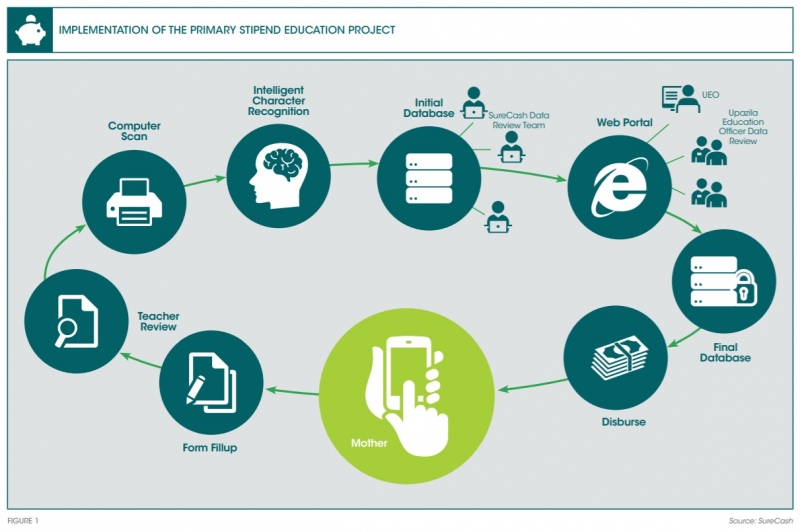

In 2017, the company collaborated with Rupali Bank to take over the massive task of digitisation of the government-led PESP. SureCash took on the responsibility of disbursing education stipends to mothers of 13 million students, and opened one mobile banking account for each mother so that they could receive the stipends directly into their accounts/mobile wallets. Once received, they could withdraw the stipend money from any Rupali Bank SureCash agent outlet, use it to make payments, or save it for the future.

As each mother listed in the programme had a bank account opened in their name, this also helped expedite financial inclusion of women and build women empowerment. Additionally, SureCash collaborated with Teletalk, whereby the state-owned telecom provider distributed a free SIM card to the stipend recipients.

Niche market strategy

SureCash was thus able to leverage a niche market strategy to its business advantage. A successful niche market strategy should ideally encompass all three of the following factors: the existence of sufficient market demand in the niche today, a low degree of competition in the niche, and a high income potential in the niche.6

In Bangladesh, women had far less access to financial services as compared to men. In 2017, 36 percent of women and 65 percent of men had mobile financial accounts, and mobile phone penetration was 47 percent for women compared to 76 percent for men.7 Hence, there was substantial market potential for innovative services for this niche segment. Second, as both bKash and DBBL were largely focused on P2P transfers, provision of other mobile financial services for disadvantaged women constituted a niche market with a low degree of competition. Third, given the population density of Bangladesh (among the highest in the world), there was a huge pent-up demand that SureCash was able tap into.

The road ahead

SureCash was able to target women and effectively implement a strategy to operate in an oligopolistic market, and its launch of the Rupali Bank SureCash PESP disbursement service has helped it find a niche in a large market. But digital disruption has begun to change the scope of markets across geographies. For instance, while smartphone penetration within rural Bangladesh was still low, in neighbouring India, smartphones had quickly gained popularity over basic mobile phones even within the poorer sections of society. The entry of smartphones into the MFS market meant a host of new service possibilities for mobile banking users. What remained to be seen was whether SureCash could continue to drive growth by partnering with other government initiatives such as PESP. And as and when the rural population of Bangladesh begins to adopt the smartphone, could the company tap on this opportunity to establish itself as the front-runner of emerging technology solutions in the MFS market?

Aurobindo Ghosh

is Assistant Professor of Finance at the Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University

Lipika Bhattacharya

is a Case Writer at Singapore Management University

1. CGAP is a global partnership of more than 30 development organisations that works to advance the lives of the poorer sections of society through financial inclusion.

2. The World Bank, “Inclusive Innovations, Mobile Money – Transforming Financial Inclusion”, 2014.

3. GSMA, “State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money”, 2015.

4. The Financial Inclusion Tracker Surveys Project, “Mobile Money in Tanzania: Use, Barriers and Opportunities”, 2013.

5. International Finance Corporation, “Achieving Interoperability in Mobile Financial Services”, Tanzania Case Study, 2015.

6. Eli Noy, “Niche strategy: Merging Economic and Marketing Theories with Population Ecology Arguments”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 2010.

7. Joep Roest, Global Findex: Behind the Numbers on Bangladesh, CGAP, 2017.