One out of every 28 people lives in a country that they were not born in. As migrants, they are estimated by The World Bank to send home US$636 billion in 2017, with three-quarters remitted to developing countries.1 These remittances form a significant percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of many of these developing countries. Given their magnitude and contribution to national economies, even a small reduction in remittance cost adds billions to these local economies. Mobile-to-mobile cross border remittances have recently shown that not only can the remittance costs be significantly brought down, but the money can also be delivered virtually in the hands of the beneficiary. We propose that with six of the top 10 remittance receiving countries of the world located in Asia, it is time to set up a Pan-Asian Mobile Remittance Platform that would enable migrants to remit money home at low cost using their mobile phones.

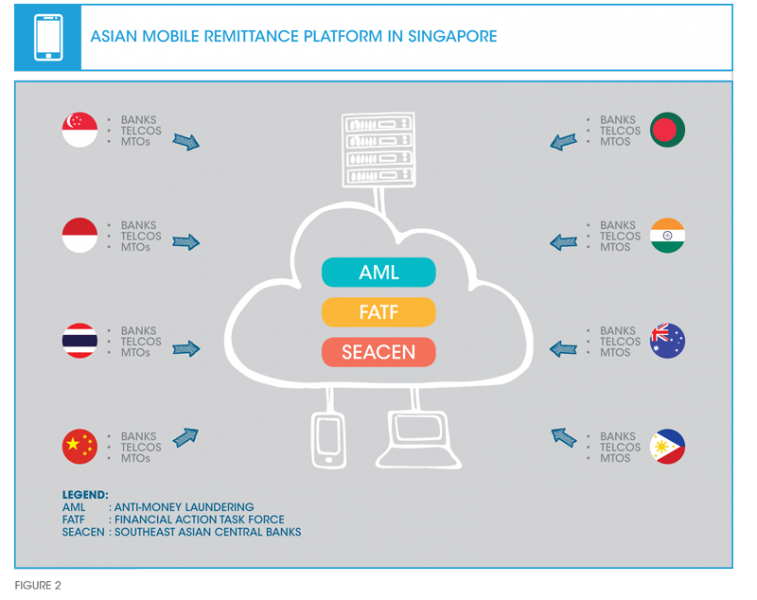

According to The World Bank’s ‘Migration and Development Brief’ report in April 2015, the number of international migrants is expected to exceed 250 million in 2015, some three million more than two years ago.2 As a result of the strong flow of migrants, total remittances in 2014 rose to US$583 billion, a six-fold increase over the last two decades (refer to Figure 1). India and China were the top recipients of these remittances at US$70 billion and US$64 billion, respectively, followed by the Philippines at US$28 billion.

A comparison of OECD and World Bank statistics shows that international remittances received by developing countries–US$418 billion in 2013–were three times greater than their official development assistance. In countries like Bangladesh and the Philippines, the share of remittances to GDP is around ten percent, while in other smaller nations like Nepal the share is as high as 25 to 30 percent of GDP, with remittances received by Tajikistan standing at a whopping 49 percent of GDP.

The impact of remittances is noticeable even at a country level within recipient states. Illustrating the case of Kerala, a southern state of India, The Economist pointed out that “2.4 million Keralites were living and working overseas in 2014. The money they send home is equivalent to a full 36 percent of the state’s domestic product...It is now about 50 percent wealthier per head than the national average.”3 To put this in perspective, with its GDP of about US$77.5 billion, the state received US$28 billion in remittances.

In 2013, international migrants from developing countries held about US$497 billion of savings in their home countries.4

International remittances received by developing countries–uS$418 billion in 2013–were three times greater than their official development assistance.

According to estimates provided by The World Bank, the global average cost of remittance has been trending downwards over the last six years. Currently, the cost of sending remittances to sub-Saharan Africa is about 9.7 percent of the amount remitted–which is among the highest in the world and about two percentage points higher than the world average. The average cost of remitting to China is also high at 9.8 percent, due to the lack of competition in its remittance market. By comparison, the average cost of remitting to most nations in South Asia is around 5.7 percent.5

According to the same report, “The cost to consumers of these remittance transactions is expensive relative to the often low incomes of migrant workers, the amounts sent, and the income of remittance recipients. Therefore, any reduction in remittance transfer price would result in a significant increase in money remaining in the pockets of migrants and their families, and would have a significant effect on the income levels of remittance families.” It further stated that “if the cost of sending remittances could be reduced by five percentage points relative to the value sent, recipients in developing countries would receive over US$16 billion dollars more each year than they do now. This added income could then provide recipients more opportunity for consumption, savings, and investment in local economies.”

What is the cost of remittance from Singapore to a major remittance destination like India? Total costs typically comprise the transfer fees and foreign exchange margins. This remittance corridor is one where the rates are lower compared to the global rate of 7.7 percent. According to The World Bank, for remittances equivalent to S$280 (US$200), the total costs charged by money transfer operators (MTOs) and banks are, on average, 4.1 percent and 3.4 percent of the amount remitted, respectively. Indeed, the entrance of new technology-driven players and the move from cash to e-money have generated innovative business models that can lower the cost of remittance services. These internet-based players earn from foreign exchange margins only, and do not charge service fees. The online remittances company, Remitguru, and online remittance portals of banks in Singapore, such as the State Bank of India, follow this business model.

Mobile remittance to be a key driver behind financial and social inclusion

According to the December 2014 report, ‘Sending Money Home to Asia–Trends and opportunities in the world’s largest remittance marketplace’ by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and The World Bank, about two-thirds of remittance centres are located in urban areas, making it time consuming and costly for rural recipients to travel the long distance to collect their remittances. The report further highlighted that cross border mobile phone-based remittance services offer several benefits over the traditional brick and mortar payment centres, such as low-cost, convenient and instantaneous transfers of funds with the added facility of being able to ‘store’ money. Such mobile remittance and payment mechanisms are thus an effective way to extend financial inclusion to the unbanked and underbanked populations in Asia, as people in rural areas are increasingly able to adopt the use of mobile phones even though they may be living miles away from the city.

Cross border mobile phone-based remittance services offer low-cost, convenient and instantaneous transfers of funds with the added facility of being able to ‘store’ money.

These ‘mobile wallets’ enable recipients to make retail payments and purchases, as well as withdraw cash, at a remittance service provider which could be a shop, post office, bank, MTO, or even an Automated Teller Machine (ATM). As the receipt of overseas remittance, along with its storage and dispensing of cash are all conducted using the same mobile phone, the ‘last mile problem’ faced by the recipient is eliminated. These simple financial innovations also create opportunities to up-sell other financial services, such as credit, savings and insurance schemes to these populations. So what was until yesterday a ‘last mile’ remittance problem can in effect be converted to an opportunity of financial inclusion to the ‘last millimetre’ in the hands of the customer.

Despite its potential to lower costs, and the added social benefits, the use of mobile technology in cross-border transactions remained largely limited until a couple of years back. International remittances sent via mobile technology, according to The World Bank, accounted for less than two percent of remittance flows in 2013, primarily due to the regulatory burden associated with such transactions.6

In Africa, large phone operators such as Vodafone, with established mobile payment networks, are slowly changing the game. With average revenue per user falling for basic voice and even data services, these companies are looking to increase their revenue from value added services, and the remittance market offers such opportunity. In 2007, Vodafone launched M-Pesa, a mobile phone payment and money transfer service in countries in East Africa. The service enabled millions of people in these countries to send and receive money, and make local payments, even though they had limited or no access to a bank account. Recently, cross-border mobile remittances were added to the national mobile payment service. With M-Pesa, the remittance costs between Tanzania and Kenya have dramatically reduced to around one percent of the transaction (plus a foreign exchange fee), even for small amounts ranging around US$50, and has made international remittances instantaneous with cash-like liquidity.

Similarly, India’s Airtel, a global telecom operator that has operations in 20 countries across South Asia and Africa, offers a payment service called Airtel Money in 16 countries in Africa. It allows its customers to transfer money across some of the markets where it operates. While using the Airtel mobile payment services, customers simply have to select the country where they want to send the money, enter the mobile number and the amount in local currency, and complete the transaction with a confirmation. According to the company, the Airtel Money service “generates a monthly average of 30-million transactions valued at US$1 billion from an active base of five-million customers”.7

We believe that mobile network operators in Asia can also play a wider role as remittance service providers by taking a share of the mobile money transfers market. A multi-currency, multi-country remittance platform can augment foreign exchange flows to the countries that are plugged into the platform. A case in point is ‘HomeSend’, an international mobile money transfer platform set up by MasterCard, eServeGlobal and BICS (Belgium’s carrier, Belgacom). Initially it operated between Europe and Africa, but now it is extending its reach to Asia.

A multi-currency, multi-country remittance platform can augment foreign exchange flows to the countries that are plugged into the platform.

A Pan-Asian Mobile Remittance Platform

The success of mobile-to-mobile payment platforms in other parts of the world suggests that setting up a Pan-Asian Mobile Remittance Platform linking major Asian recipient nations can bring enormous benefits to the individuals and economies in Asia.

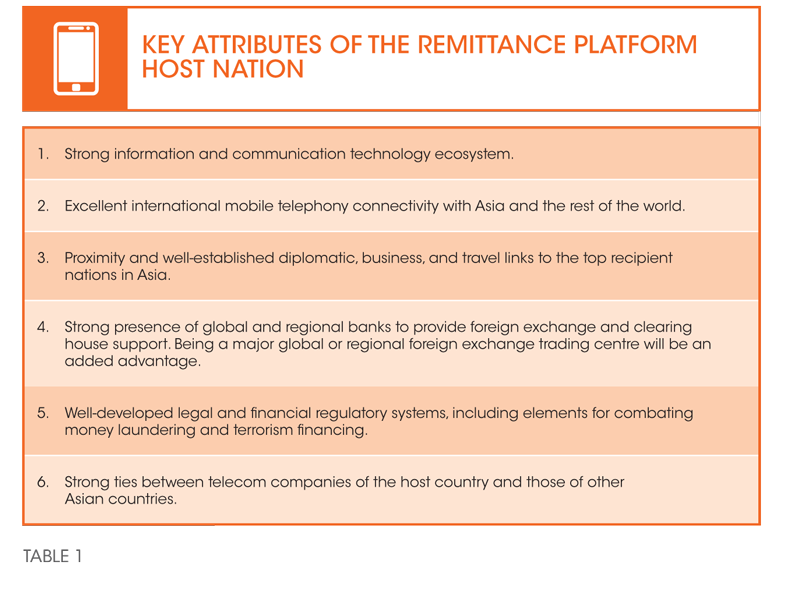

Any Asian nation with a well- developed foreign exchange market and a sizeable immigrant population that carries out a considerable volume and value of remittance transactions to other Asian countries could potentially take the lead in developing such a platform. A country like Singapore is well-placed to lead this effort, as it fulfils many of the criteria for a good platform host, as listed in Table 1.

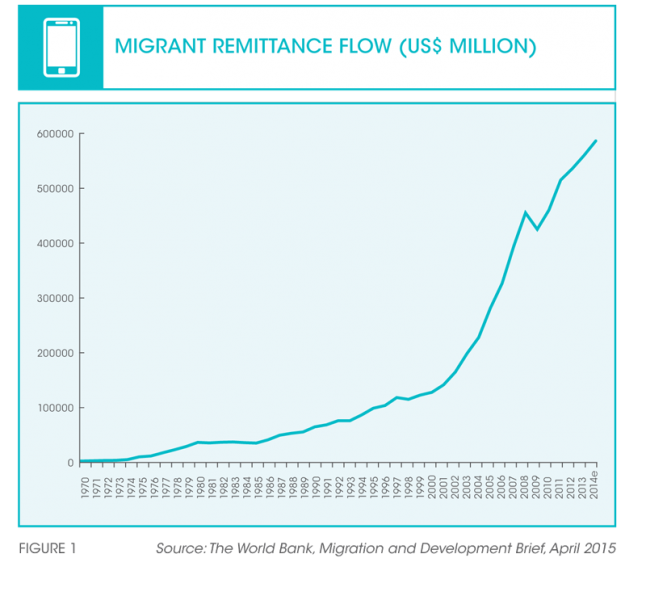

Singapore is already the largest foreign exchange centre in Asia, and the third largest in the world after London and New York.8 If a Pan-Asian Mobile Remittance Platform that links major Asian remittance recipient nations is set up in Singapore, it can become the payment and remittance gateway to millions in Asia. The country has a robust global financial services sector, coupled with strong IT and telecom infrastructures, which are prerequisites for such a platform (refer to Table 2).

Singapore also has strong trade, investment, and historical relationships with China, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Together with Bangladesh, these are also the countries from which migratory blue and white collar workers come and work in Singapore. As these countries are among the top ten remittance-receiving countries, their national telecom companies are assured of billions of dollars of remittances that can flow through this platform and through their network to their mobile subscribers. They also have a social role to lower remittance costs by participating in the Pan-Asian Remittance Platform. In addition, they can facilitate cashless transactions in their countries, with their own mobile networks being the enablers.

In addition, some of Singapore’s leading telecom companies have stakes in other telecom companies in the region, and the connectivity to link up with a critical mass of these national players. For example, Singtel has a 32 percent stake in Airtel India, which is itself building a pan-African mobile payment platform–and those experiences and lessons learned in Africa can be useful in developing a platform in Asia. Singtel also has a 47 percent stake in Globe Telecom of the Philippines, a 45 percent stake in Citycell of Bangladesh, a 35 percent stake in Telekomsel of Indonesia, and a 23 percent stake in Advanced Info Service of Thailand. Australia’s second largest telecom operator, Optus, is fully owned by Singtel, and Australia is an important source of remittances with destinations to India, the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand. Similarly, Starhub, another Singaporean telecom service provider, is also very well connected with other similar companies in each of these countries.

Some progress has already been made in this direction. Singtel has launched in Singapore a mobile remittance service called ‘Singtel mRemit’. This selfservice remittance mechanism allows the users to remit to the Philippines, Indonesia and India using their mobile phone. For a fee ranging from S$2.50 for the Philippines, S$4.00 for India, and S$7.50 for Indonesia, customers can remit money to most major banks and partner ATMs in these countries.

A Pan-Asian Mobile Remittance Platform set up by Singapore, together with these national telecom companies in the region, would create a huge remittance-recipient network with many millions of subscribers. It may possibly be the largest such remittance aggregation and distribution network anywhere in the world. Once such a network is formed, one can expect the telecom service providers of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and other middle-eastern nations to also establish strong ties with such a network.

A white paper produced by SWIFT in May 2012, ‘Mobile payments: 3 winning strategies for banks’, argues that “mobile payments are rightly a top investment priority for banks globally–unsurprisingly, since out of a world population of seven billion, more than five billion (70 percent) have mobile phones, while only two billion (30 percent) have a bank account. This fast-growing market is predicted to carry US$1 trillion in transaction value by 2015.” The SWIFT report also cautioned that “deploying mobile payments is not as straightforward as legal frameworks across countries are not harmonised, technology is still evolving, [and] there is a need for multiple partnerships…”.9

We agree that such cross border payment platforms must conform to legal and regulatory frameworks to ensure that they do not become a means for money laundering and terrorist financing. Herein the central bankers and financial regulators have a strong role to play to facilitate formation of such cross border mobile payment and remittance platforms across South and Southeast Asia. Fortunately they do not have to start from the scratch. Central banks of the region have already come together under the banner of The Southeast Asian Central Banks (refer to Figure 2). This grouping could bring the central bankers’ perspectives of facilitating cross border remittances to this platform. After all, as many of these nations are major recipients of the international remittances, it is in their interest to make it cheaper, easier, faster and safer for their residents to receive money.