How do Japanese corporate groups manage their subsidiaries?

As companies grow in size and diversify their operations either in domestic markets or overseas, the number of subsidiaries tends to increase and the structures of the companies become more complex. Nowhere is this trend more visible than in the case of Japanese corporate groups, a majority of which in 2014 were reported to have 50 or more subsidiaries each. Among the largest corporates, Sony had 1,240 subsidiaries, Hitachi 1,008, NTT 917, Softbank 796, ORIX 766 and Dentsu 707.1

Effective leadership is always a challenge, but managing subsidiaries comes with additional complications. Subsidiaries operate in the shadow of the larger parent organisation and corporate management needs to address both the parent organisation’s primary mission and the subsidiaries’ goals. Governance, reporting and employee needs and motivation must also be balanced across the subsidiaries. All in all, having a multitude of subsidiaries creates a daunting task of coordinating masses of activities across the organisation.

The control and coordination of subsidiaries has become increasingly relevant in Japan today where, as pointed out by Miyajima and Aoki,2 we are witnessing an increasing number of cases of information asymmetries between the corporate head office and its many layers of internal organisations and subsidiaries. Meanwhile there has been a move toward enforced legal responsibility of corporate board members. Statutes protecting shareholders now mandate that management and boards ensure the appropriateness of activities across the organisation. Negligence in monitoring obligations can lead to litigation from shareholders. This shift begs the question: How can a Japanese corporation effectively control, coordinate and manage its subsidiary businesses across the organisation?

Parent-subsidiary relationships

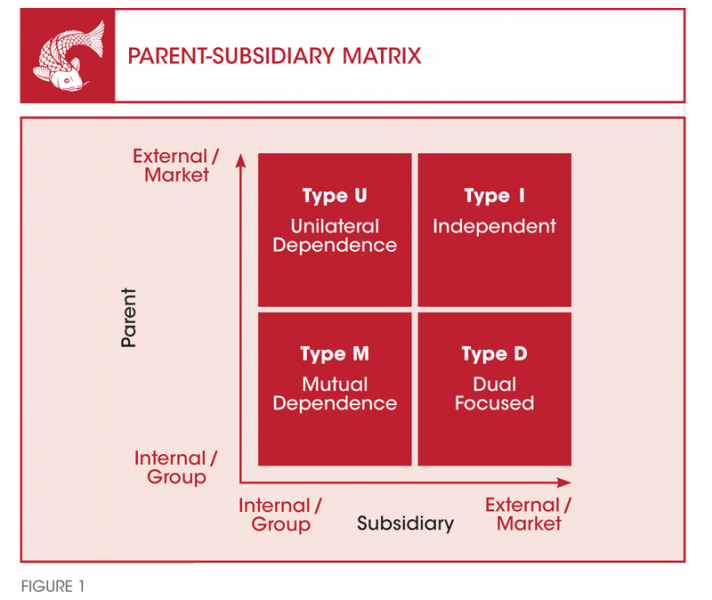

It is useful to identify and classify the different types of parent-subsidiary relationships that exist, and treat them separately rather than generalising them as homogenous. Through a series of interviews and discussions with five large corporate groups in Japan, I have constructed a conceptual classification based on the dependency relationship between the parent company and its subsidiary, which may be unilateral or mutual. The relationship is unilateral when the parent depends solely on its subsidiary for production inputs, or when the subsidiary depends on its parent as the only client and source of revenue. It is mutual when both the parent and the subsidiary depend on each other. They may trade either internally within the group, externally with outside clients, or engage in both. Figure 1 illustrates how the parent-subsidiary relationships can be classified into four main categories.

UNILATERAL DEPENDENCE (TYPE U)

A subsidiary belonging to this type depends on its parent as its main trading partner (client) and source of revenue. The subsidiary usually has expertise in one area that contributes to the larger product or service value chain of the parent. The parent company, however, regards the subsidiary as one of many trading partners (suppliers) in the market, and cherry picks between using the subsidiary and market for favourable price and quality, whilst also maintaining an acceptable subsidiary utilisation rate.

In such a situation, the subsidiary typically has weak bargaining power when negotiating with its parent, and may strive to be at least as competitive as the market in order to win orders. In the case of Kawasaki Heavy Industries, for example, the parent company deliberately treated its subsidiary as a Type U so as to enhance the subsidiary’s competitiveness and make it at least on par with that of other suppliers in the market. However, the parent company may also abuse its power by demanding flexibility in production and lower costs such that all profits are absorbed and taken away by the parent, in which case the subsidiary may lose either a) the incentive to be entrepreneurial, b) any retained profits earnings and cash fl ow to assume greater risk or c) the capital needed to innovate, upgrade and remain competitive. Overall, less coordination is required between the parent company and subsidiary because the parent is not dependent solely on the subsidiary’s output.

MUTUAL DEPENDENCE (TYPE M)

A subsidiary in this quadrant sells its goods and services primarily to its parent company. The parent too is highly dependent on the goods and services its subsidiary provides, and may often exert control over decision making even on matters concerning day-to-day operations. Having such a subsidiary helps to enhance a firm’s specific specialisation whilst also reducing labour costs and thereby facilitating cost competitiveness. Mutual dependence is often inevitable when there are no other suppliers in the market that can substitute the functions performed by the subsidiary, or when there are concerns of proprietary technology being copied or imitated.

Of the companies that I have interviewed in Japan, many have subsidiaries that fall into the Type M category. One example is the Japanese electronics company, Sharp. Between 2005 and 2009, when many television manufacturers such as Sony, Samsung, Philips and LG began to outsource their LCD panel production to allow for expansion in a growing overseas market, Sharp continued to invest in and focus on using its in-house produced LCDs, which the company believed to be technologically advanced and hence crucial to its product differentiation strategy.

The Type M subsidiary may need to balance between building firm-specific production knowledge within the group and acquiring knowledge and new technologies that are accessible through working with external clients. Lock-in and inertia may arise when switching costs are high, and appropriate monitoring is needed to root out inefficiencies. Mutual dependence deems it necessary for the parent and subsidiary to coordinate regularly. Decision making may be more centralised for Type M relationships.

DUAL FOCUSED (TYPE D)

A Type D subsidiary sells its goods and services mainly to external clients in addition to its parent company. Between 2013 and 2016, Panasonic shifted its white goods subsidiaries from Type M to Type D as it expanded into the business-to-business segment using its nanoe generator technology (using nano-sized electrostatic atomised water particles) which had, until then, been used in many of Panasonic’s products such as refrigerators, washing machines and beauty products.

Under the Type D model, the parent company, which is highly dependent on its subsidiary’s output, may want to exert control over its subsidiary, and this may lead to a conflict of interest. For example, a subsidiary may wish to mobilise its resources to expand sales outside the corporate group, but its parent company may want the subsidiary to reduce its external sales and focus its limited resources on the internal supply chain. Managers may be transferred or seconded from the parent to such subsidiaries to act as effective coordinators and mediators.

By having a subsidiary shift more towards external sales, both the parent and the subsidiary could benefit from economies of scope and scale if the subsidiary manages to reduce its marginal cost of production. Participation in the market will also force the subsidiary to be more competitive in quality and price, and the parent company may benefit from such external governance and the leveraging capabilities of the subsidiary.

Because of the dual pressures that a Type-D subsidiary often faces, careful coordination and control is required so as not to curb the subsidiary’s entrepreneurial incentives, whilst ensuring that firm- specific investments needed for the parent company’s business are also maintained.

INDEPENDENT SUBSIDIARY (TYPE I)

A subsidiary belonging to this type sells its goods and services mainly to its external clients. The parent too is not dependent on the subsidiary’s function and sees it as a separate revenue generating business within the corporate group’s portfolio.

A subsidiary may initially be established as Type M, performing specific functions within the production value chain of the parent’s core business, such as manufacturing a certain component or performing logistic functions that support the corporate group’s supply chain. As the subsidiary gains experience and expertise in servicing its parent company, it gradually develops competencies that could be applied to other production settings with external clients. The subsidiary may eventually itself become a core business segment within the corporate group, and make substantial contributions to consolidated revenue. This was the path that Hitachi Transport System has taken. It began as a Type M subsidiary offering excellent logistics solutions and gradually evolved over time into a successful Type I subsidiary that provides third-party logistics and other services to many external clients. At Hitachi, better performing subsidiaries are granted more discretion over decision making and hence have more incentive to perform well. A Type I subsidiary requires little control and coordination. However, the parent company may exert control when performance drops.

Using the parent-subsidiary typology matrix, companies can identify their current parent-subsidiary relationship and adjust to better ways of coordinating business activities.

Roadmap to creating a successful subsidiary

Although it would be impossible to prescribe a one-size-fits-all success formula that works for every corporation and its subsidiaries, it is possible to draw some general implications that can be applied towards developing mutually beneficial and successful parent-subsidiary relationships. The simple roadmap outlined below highlights what companies should consider when managing subsidiaries.

IDENTIFY AND EVALUATE THE CURRENT PARENT-SUBSIDIARY RELATIONSHIP FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF BOTH PARTIES

The first step is to evaluate the present parent-subsidiary relationship. The role of a subsidiary as perceived by the parent may be biased, and it is only when the perspective of the subsidiary is also added that the picture becomes complete. The parent-subsidiary matrix allows both the parent and the subsidiary to identify issues from their respective perspectives, facilitate discussions and foster shared understanding. Mutual agreement and consensus are important characteristics of Japanese corporations as they allow control and coordination to function alongside decentralisation (refer to Figure 2).

|

REACHING MUTUAL CONSENSUS |

||

|

|

Parent Company |

Subsidiary Company |

|

Type U

|

It is cheaper to procure from the market because the product has become modularised and commoditised. But doing so will reduce operations of its subsidiary and will incur losses which the parent will have to cover. |

The parent is the only client, such that when it cuts production or procurement, the subsidiary loses its sole source of revenue. The subsidiary has been trying to fi nd other external clients but has not been successful. |

|

Possible Consensus: Parent to transfer skills to the subsidiary to help improve productivity so that the subsidiary could gradually shift to Type D. Subsidiary to strive to be competitive in the market. If improvements are not made within an agreed time frame, the parent will close down the subsidiary or use its resources for production in another business division. |

||

|

Type D |

Depends heavily on inputs from the subsidiary and hence exerts centripetal pressure. The parent however also benefits from economies of scale its subsidiary brings through business with external clients. |

Although generating healthy profits, the subsidiary faces constant pressure from the parent to focus its production resources on the parent’s products, as well as to cut down on investments that are considered not firm-specific. |

|

Possible Consensus: Give priority to the parent’s product, as the corporate group’s core growth driver business. |

||

|

Type M

|

The subsidiary provides highly firm-specific products that cannot be procured from the market. Hence it is not easy to determine transaction price for there is no market price to allow for comparison. The business unit is profitable, so there is little incentive to stretch its subsidiary’s targets. |

Business with the parent has become routine and there is no need to worry about fierce competition (which having external businesses would entail). Although there is no intentional milking of profits from the parent, there is little incentive to innovate. |

|

Possible Consensus: Use non-financial key performance indicators to monitor and motivate performance, as well as monitor the subsidiary’s procurement costs. |

||

|

Type I

|

Parent noticed that multiple business subsidiaries are developing and producing similar products individually. |

Profitable with relatively high degree of autonomy. Becoming industry leaders in their own field. |

|

Possible Consensus: Combine multiple businesses and rebrand the corporate group as a fully integrated solutions provider. Decision rights to the subsidiary will be contingent upon performance. |

||

Figure 2

ALIGN PARENT-SUBSIDIARY RELATIONSHIP WITH STRATEGY

After having identified the subsidiary type based on existing parent subsidiary relationship, the next step is to define or re-define the role of the subsidiary so as to ensure that it is aligned with the corporate group’s strategy. A mutually agreed solution between the parent and the subsidiary may result in the role of the subsidiary remaining unchanged, or in the subsidiary shifting from one type to another.

A key part of this process is to recognise and evaluate appropriately the capabilities of the subsidiary. As pointed out by Birkinshaw and Morrison, parent companies are not always aware of their subsidiaries’ capabilities.3 In addition, a subsidiary’s contributory role within the corporate group depends greatly on the parent and subsidiary relationship, the subsidiary’s initiative and entrepreneurism, and the parent’s recognition of the subsidiary’s capabilities. Some ways to ensure adequate parent-subsidiary communication and coordination are further explored in Figure 3.

|

COORDINATION, DELEGATION AND MANAGEMENT BASED ON PARENT-SUBSIDIARY TYPE |

|||

|

|

Coordination |

Delegation |

Relationship |

|

Unilateral Dependence (Type U) |

Improve competitiveness such as by coaching and transferring skills from parent company. |

Foster independence and entrepreneurship. |

Quasi-market like relationship, though need also to consider utilisation and revenue of subsidiary. |

|

Mutual Dependence (Type M) |

Work closely to share tacit knowledge and leverage capabilities of subsidiaries. |

Because of dependency, major decisions may be centralised. Need clear role definition to empower and maintain incentives. |

Be careful not to allow routine transactions to breed inefficiencies. Benchmark market prices, and where necessary, revise trading terms. |

|

Dual Focused (Type D) |

Control subsidiary as both profit and cost centre. Decide whether scarce resources should be used to develop firm-specific competencies for the company or for external businesses. |

Increase control when there appears to be conflicting interests that could negatively affect the overall optimality of the corporate group. |

Conflict of interest may arise because of dual pressures from internal and external businesses. Try to mutually agree on scenario that maximizes group performance. |

|

Independent Subsidiary (Type I) |

Coordination focused on portfolio management and overall optimality. Part of the subsidiary may be severed from the subsidiary’s control and incorporated instead into the group’s growth driver division. |

Delegation contingent upon performance. Despite autonomy that is granted to the subsidiary, if it constitutes a major source of revenue to the group, then decision rights on major strategic issues may still rest with the parent company. |

Relationship likely to be closer if the subsidiary is a core business or if it has synergies with the group’s core business, and distant if it is a non-core business. |

Again, there is no one-size-fits-all solution and, in reality, many activities often entail trade-offs. For example, a Type M (mutual dependence) subsidiary may become less competitive over time because of the absence of market discipline and availability of new external technologies. Therefore periodic evaluation is necessary to see whether assigned roles are still valid and coherent with the firm’s strategy, or whether over time, objectives have changed, deeming it necessary to revise control and coordination.

The framework thus facilitates a continuous, iterative process that helps the organisation adapt and adjust as it grows, matures and faces new market situations. Having a ready framework to analyse complicated group management issues allows managers to have a better grasp of activities that require attention, continuously update and refresh information, and tailor control and coordination measures based on a better understanding of evolving parent and subsidiary relationships.