Rethink brand building through the concept of platform brands. Their key tenets—participation, personalisation and shared purpose—lay the foundation for transforming a brand.

Consumers are getting used to the notion of businesses as platforms—think Uber, Didi, Airbnb, eBay, Alibaba, Twitter, Google Search, Facebook, or PayPal. They are among the biggest businesses in the world today and yet do not necessarily themselves produce, own, or sell a product or service. What they do instead is provide the platform for the products or services to be traded. In addition, they derive value from the accumulation of the intelligence associated with these exchanges. These platforms acquire huge amounts of data on everything from their customers’ profiles and behaviours to their desires and thinking.

From a consumer perspective, these brands have become part of our everyday lives and we participate in these platforms while taking for granted the market revolution that is taking place. In reality, platforms are shaking up industries and disrupting markets. They grow exponentially, driven by ‘network effects’, which refer to the multiplier effect where more producers attract more consumers and vice versa. They spread out to become multi-sided markets and networks across adjacent categories.

From pipeline to brand platform

The shift from products and services to platforms manifests as a transformation from businesses driven by production economies to businesses driven by demand economies of scale. Let us go back to the beginning with the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) business model. Since World War II, the FMCG supply-driven model has reigned large. Under this model, we have a producer and their (ideally) proprietary pipeline that is all about generating units of a product or service, pushing these units into the marketplace, and then scaling up production.

To push people to buy their products, producers imbue their products with physical and emotional characteristics that are attractive to their target audience. These strategies to create a differentiated offering are often referred to as the ‘brand platform’. The act of ‘pushing’ became more important as scaled production of consumer goods started to significantly outgrow demand in developed markets. The more producers can scale up their production volume, the lower their costs and the greater their prodit margin, or ability to lower prices to defend their turf.

Platform brands, however, are an entirely new species.

From brand platform to platform brand

Platform brands, in most cases, do not actually own the assets that produce the goods or services. They might not even own the intellectual property to the product or the capital. In other words, they do not own the goods or services that are being sold under their brand. For example, Airbnb is now one of the biggest hospitality businesses in the world but it doesn’t design or own a single hotel room, nor does it host guests, or deal with any of the associated services (like cleaning and security). All it does is provide the platform on which hosts and guests can find each other and execute the ensuing financial transactions. Platform brands are simply the connector of data and money flows. What platform companies do is provide the infrastructure and impose the rules under which the participants can operate.

On many platforms, a consumer might switch to become a producer and vice versa. For example, within Airbnb, you might be a producer in that you are a host. But when you travel, you become a consumer, in that you are now a guest. Similarly, when you do a search on Google, you are a consumer as you receive a service by way of obtaining information. Simultaneously, you are a co-creator on Google, because with each search, your data makes Google smarter about things and you help it produce better search results.

This last example illustrates another key distinction: Unlike the traditional brand platform, platform brands are not driven by supply but by participation. With every transaction, platform brands learn more about the drivers of supply and demand. The more people engage with a platform, the smarter it gets and the more relevant it becomes with better offerings and more demand. With every new participant, the Airbnb offering becomes richer for travellers and more lucrative to hosts, while with every search, Google searches get smarter.

Participation at the core

Platform brands are different in that the ‘consumer’ becomes a ‘participant’ who is involved in the creation of the product. We find that participation, coupled with the elements of personalisation and a shared purpose, can be commanding elements of a strong platform brand, if harnessed well.

PARTICIPATION

Platform brands can give people a stake, a voice. They can give them a sense of ‘belonging’. Compare selling flour through supermarkets with that of offering cooking classes where people gather to experiment and learn how to use the flour—what a profound difference in customer experience! Passengers who have connected with a driver on a longdistance trip on the BlaBlaCar platform feel differently about the driver and the journey than commuters who merely hopped onto a scheduled bus. At Airbnb, the participatory and very personal experiences associated with ‘social travelling’ are summarised in ‘Belong Anywhere’—expressing a shared purpose rather than just a simple tagline or slogan.

PERSONALISATION

Airbnb offers programmes and experiences that are becoming almost infinitely personal in terms of the possible choices. Airbnb hosts are proud owners of their style and they connect with potential guests based on shared interests and tastes. Similarly, the pet food brand Mars Petcare is transforming from a maker of dog and cat foods to a pet well-being platform where products like smart collars enable the provision of personalised (and increasingly predictive) health, entertainment, and nutrition services and products.1

PURPOSE

Platform brands can be differentiated by how their platform rules of participation reflect their set of beliefs, and by their purpose, which attracts some people more than others. They might have a meaning, a higher mission that goes beyond their products and services. For instance, the U.K.-based insurance company VitalityHealth’s shared purpose is to nurture a long, healthy life of the insured/participant.

Co-creation through participation is a powerful force in the service and B2B area too, as office software Slack illustrates. Developed by Slack Technologies, the solution provides software tools and online services for team collaboration. What makes Slack different is that the company provides a platform that integrates external apps and software, and encourages independent developers to innovate and build upon the platform. The declared purpose is to create a work environment that is more efficient and pleasant. In order to encourage more to participate, Slack has created a fund to support the development of the best ideas.

That is what participation can do for you as a brand; it transforms brands from just being a producer of goods to a platform for relationship-building and co-creation. The more a brand is able to engage its users, the more dynamic, relevant and powerful it becomes in a virtuous cycle of growth.

How platform brands outperform

Platforms and networks are increasingly proving to be a formidable way of providing goods and services for what people need across industries.

To begin with, platforms are more diverse in their offerings. Airbnb can offer more differentiated rooms and more diverse experiences than any hospitality provider can. Second, platform brands are also more agile and faster than any centralised producer and provider can be. For instance, Amazon Marketplace can offer more products and pick up on trends faster than any other retailer. Third, platform brands have the power to create truly transformational businesses through the dynamics of the many networks of connections that they offer.

Take Vitality. Created by the insurance company Discovery in South Africa, the Vitality health programme allows Vitality members to earn Vitality Health points by getting active, eating well, and doing their health checks. Members enjoy a variety of rewards at each Vitality Health status level, and their status elevates as they get healthier. Besides South Africa, this programme is offered in the U.S., the U.K., France, Italy and Singapore. Vitality has a shared goal with health insurance partners of enhancing the health and protecting the lives of their members. So they work with members and partners, and reward members for staying healthy. The programme hands out Fitbit devices and Apple watches to keep their members healthy and exercising, and in return, members enjoy a reduction in premiums or a reward of their choice. Vitality’s network embraces insurance companies, sportswear brands, supermarkets, Starbucks, gyms, supermarkets, pharmacies, airlines, Uber, and more. Their data shows that its members are healthier than the competition’s because of this programme. And all of it is driven by embracing participation and by binding its partners and consumers to the platform through a shared common purpose. With the success of its network approach, Vitality is transforming the entire insurance business.

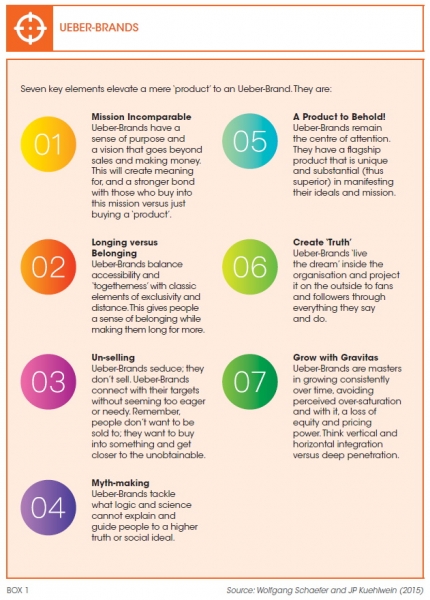

What do these structural differences mean for platforms as brands? Our first look suggests that platform brands have the potential to be strong brands. This is because participation and personalisation, together with a sense of belonging and a shared purpose, are also what we find to be principal drivers of the desirability and success of modern prestige and lifestyle brands. These brands—we call the strongest of them ‘Ueber-Brands’—create a sense of belonging and personalise their offerings to be among the strongest, peerless and priceless (refer to Box 1).

A pioneering example of a traditional pipeline-packaged goods manufacturer investing substantially into becoming a platform is the aforementioned Mars Petcare, which has grown far beyond its core products. The company has invested US$14 billion since 2016 into several dozen businesses to form a network that has generated US$17 billion in sales. A substantial investment no doubt. Today the richly networked business has healthcare centres, a pet research unit, pet hospitals, a nutrition institute, and an invention studio that invests into new pet ideas. The company has created a programme called ‘Kinship’ through which it reaches out to start-ups and outside companies to join its network with their unique pet-related expertise and solutions. It is also networked with Better Cities for Pets, a campaign that sponsors ways to make cities more pet-friendly. The firm shares with city authorities and volunteers what it knows about pets.

Mars Petcare demonstrates what a network can bring to the party. Its entire network connects up: data from the nutrition institute informs the firm’s pet food and pet hospitals, while data from the firm’s research unit steers its healthcare centres. Mars Petcare consumers can participate on a personal level and subscribe to the world of Mars Petcare. Or they can choose to participate on a higher level to help make the city more pet-friendly, to help in DNA research, or help other pets be more healthy. Because of this network, Mars Petcare can almost know what your pet needs before you do. The potential to create one purposeful, participatory, personalised platform for pets and their guardians is truly a breakthrough. Mars Petcare could evolve into a truly formidable Ueber-Brand.

The possibilities are immense… but so are the barriers

Despite this potential to appeal, why aren’t most platform brands dear to our hearts?

In fact, the contrary is true for many of the leading platforms. Many people have started to be antagonistic towards Google, Facebook, Uber, and Amazon because people realise they are becoming dependent on their services. It is partly because stakeholders are not rewarded with a just distribution of control, power, and money for their participation. Take Uber in the United States. While the platform gets most of the control, power, and profits and the passengers gain some control and power, the drivers have little control and struggle to make a living.

Participation is a really strong force, but if it is not built on interdependency, there is the risk that consumers do not trust the brand and it backfires. Backlash happens when the benefits of participation and purpose are one-sided and the platforms do not serve all stakeholders equally and fairly. In many cases, there is no higher purpose to speak of, resulting in platforms that are no more than efficient product delivery machines that spy on you.

This is happening with many platform brands right now. People are upset with them for lapping up all their data. They do not get to decide what is being done with their data, nor participate in the value that is being created by it. Consumers and users claim these companies are tracking them through the iPhone, listening to them through Alexa, and harvest every email exchange for consumer intelligence–including the attachments. Any email you send, Google owns it, Google has analysed it, and Google has attributed it to you.

Unless there is interdependency and people have rights and responsibilities in the game and can truly participate, there is a danger of an Orwellian scenario developing with one omniscient power knowing everything and the powerless consumer owning nothing. To avoid such as dystopian scenario, or rather a popular or regulatory backlash, brands should embrace participation and harness its tremendous benefits. It is important to find out what forms of participation your target community is really keen on and wants to pursue, and this is no simple task.

The risk is high that somewhere en route to becoming a powerful, omniscient network, the brand begins to exploit the power of its network. John Deere, the American manufacturer of agricultural, construction, and forestry machinery, is leveraging technology in astonishing ways in the agricultural industry. It monitors the weather, tracks seed yields, captures the fertility of land parcels by the millimetre, and records the yield of each farmer, the machines used, and the maintenance of those machines. John Deere offers farmers a network that links up the weather forecast, the seed makers, the fertiliser makers, and more. With all the data provided by farmers, the network is able to offer farmers precise recommendations on everything—from soil, seeds and fertilisers to equipment—to optimise yield.

However, as the collector and owner of the data, it is up to John Deere whether it wants to share the data with the farmers who help populate it. Farmers have now become dependent on John Deere. The company can also detect faults and maintenance issues through its network of sensors and has been known to force farmers to only use its workshops for tractor repairs–to the point that the machine risks being remotely incapacitated by John Deere if it detects that the machine is being ‘tampered’ with by some other agent.2

If’s and but’s

Platform brands have inbuilt monopolistic tendencies that may potentially lead to backlash. Equally, network effects tend to lead to ‘winner takes all’ outcomes. And the ‘always-on’ connectivity can result in dependencies that many feel are addictive or invasive, or both. These potential risks are a call-out to governments to consider regulatory action. In some ways, platforms are no different from the mighty industrialists, the ‘Robber Barons’ of the industrial age, except that they leave the manufacturing to others.

We believe finding a shared purpose and ensuring a fairer distribution of the benefits arising from participation can go a long way in gaining support and ‘de-commoditising’ the offerings. Imagine if Uber drivers were given more means, i.e., margin, to increasingly personalise their services instead of hurrying from trip to trip to make ends meet. Airbnb is a pioneer in doing just that; it has so far been able to rally the support of both hosts and travellers against restrictive legislation in New York and other cities because they are sharing more fairly. Vitality and Mars Petcare may avoid backlash if the purpose behind their data gathering remains squarely focused on creating a positive payout in the form of improved health of participants.

The possibilities for platform brands that leverage the 3P’s—participation, personalisation and purpose—to create a shared and equitable experience for customers are immense. In theory, platform brands could become beloved Ueber-Brands. They have inherent strengths when it comes to building the high engagement and affinity that consumers seek today. They have the participatory DNA that allows them to go beyond convenience and connectivity to offer meaningful experiences. It remains to be seen how many will see the light and take the leap.

JP Kuehlwein

is the Founder of Ueber-Brands and Adjunct Professor of Marketing at NYU Stern School of Business

References

1. Mars Petcare has over 85,000 Petcare Associates that are involved in every aspect of pet care from nutrition (through foods like Pedigree, Whiskas and Royal Canin) to high-quality medical care provided by Banfield Pet Hospitals, VCA and AniCura.

2. Kyle Wiens and Elizabeth Chamberlain, “John Deere Just Swindled Famers out of their Right to Repair”, Wired, September 19, 2018; and Adam Minter, “U.S Farmers are being Bled by the Tractor Monopoly”, Bloomberg, April 23, 2019.