The year 2015 is only symbolic for the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), as the region has been moving towards economic integration for some time. Tariffs for most manufacturing goods have already fallen to low levels between the member nations. Capital is moving freely across member countries—for example, the Philippines already allows 100 percent foreign equity in local banks. Service professionals, with the exception of some like lawyers and architects, continue to practice and work across ASEAN borders. At the other end of the spectrum, we do not expect the free fl ow of labour for a long time to come. Still, 2015 may be significant for agricultural commodities like sugar and palm oil, which until now have been protected by subsidies to local producers and/or high import tariffs.

There is a lot of talk about how Filipino policy makers and businesses should prepare for and take advantage of the opportunities offered by the AEC. The reality is that Philippine enterprises have been investing and doing business in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam since the early 1980s. Their experiences, both positive and negative, serve as a good starting point for policy makers and businesses to strategise on which domestic sectors to focus on, where to invest and how to conduct business in order to benefit from the integrated community. Even more important, the Philippines needs to take some bold measures to put its own house in order to be an attractive place for business.

In order to plan ahead, one must learn from the past. The Philippines economy has gone through many ups and downs in the last 60 years. Past political regimes—whether open or closed, regressive or reformist, dictatorial or democratic—have left their indelible marks on the economy. Though mooted as one of the most promising economies of Asia in the 1950s, the Philippines witnessed a systematic degeneration of its economy in the decades that followed (refer to Box Story below).

|

THE PHILIPPINES: A CHEQUERED 60 YEARS In the mid-1950s, the Philippines was ranked the second most progressive country in Asia, after Japan. With its large, educated, English-speaking population and prospering industries, it was poised for rapid growth and development. After 1965, the inward-looking policies and controls imposed by Ferdinand E. Marcos’ government hampered, and even stunted, economic development. In the two decades that followed, the Philippines experienced severe economic hardships, marred by corruption and social unrest. Trade declined, investor confidence dropped, industries weakened, growth suffered and a large part of the population was trapped in poverty. In 1986, through a peaceful ‘People Power’ revolution, the authoritarian government of Marcos was overthrown and Corazon Aquino took over as president. A new constitution was approved in 1987. Despite several attempted coups d’état, natural disasters and severe power shortages, the Aquino government was able to establish democratic rule in the country. Some initiatives were also taken to revive the economy. However, it was Fidel Ramos, Aquino’s successor, who pushed through bold economic reforms under the ‘Philippines 2000’ development plan. During his six years in office (1992 to 1998), he focused on industrialisation, privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation. Several infrastructure sectors such as electricity, communications, banking, shipping and oil were privatised. The Philippines’ taxation system was reformed, and external debt and inflation were brought under control through debt restructuring and prudent fiscal management. The Estrada government, which took over in 1998, and in particular the visionary Secretary of Agriculture, Edgardo Angara, helped to refocus national efforts toward agriculture, an ignored sector with otherwise huge untapped potential. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 had an adverse impact on all economies in the region. Although the Philippines managed to fare better than some of its neighbours, the nation also saw a change in leadership which added to its economic woes. Within three years, in 2001, the Estrada government was overthrown by a second ‘People Power’ revolution, which placed Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo at the helm as president of the nation. Since then, the Philippine government has been making a sustained effort toward growth, policy reform and liberalisation. The Arroyo government also took proactive measures toward agricultural and rural development. Recognising the budgetary constraints of the government, Arroyo emphasised public-private partnerships (PPPs) as a means to develop the country’s infrastructure. The current president, Benigno Aquino III, is taking these initiatives to the next level. |

After six decades of repeated boom and bust economic cycles and almost two decades of slow and painful reforms, the Philippines is once again poised to attain sustained annual growth rates of 7 to 10 percent. The effects of the strong and sound economic policies of the last 14 years are clearly reflected in the country’s growth performance—GDP growth rose from 3.7 percent in 2011 to 7.2 percent in 2013.1 The country achieved 6.9 percent growth in GDP in the last quarter of 2014, establishing three years of continuous growth for the first time since the mid-1950s.2

The Philippines achieved 6.9 percent growth in GDP in the last quarter of 2014, establishing three years of continuous growth for the first time since the mid-1950s.

Tapping into ASEAN and beyond

Since 2001, major players such as the Salim group (Indonesia), Singtel and Keppel Corporation (Singapore), and Charoen Pokphand (CP) Group (Thailand) have established their presence in the Philippines, resulting in a continuous increase in portfolio investment in the country. Toward the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, Philippines-based food and beverage enterprises began expanding their operations to select ASEAN countries: the Robinson Group, Liwayway Manufacturing (Oishi brand), Century Pacific, Jollibee and Nutri Asia being noteworthy cases in point. Many other companies traversing ASEAN even earlier, such as accounting firm Sycip Gorres Velayo & Co. (SGV & Co.), pharmaceutical company United Laboratories and brewer San Miguel Corporation. Admittedly, these already globalised enterprises are the exception in the generally inward-looking, insular, ultra-nationalist and protectionist Filipino business community. But times are changing. And these changes can accelerate if, instead of worrying about what governments will do to promote or block regional integration within ASEAN, Filipino entrepreneurs simply follow the lead of the pioneers who went international despite uncertainties in government policies and the geopolitical environment.

These measures to open up the economy will not only help the country compete better in ASEAN, but also globally. Hence, although the ASEAN nations would be trading and investing in each other’s countries more and more, the Philippines should not be closed to the rest of the world. A good example of this is the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry in the Philippines, which earns over US$10 billion annually from the U.S. alone. With earnings of US$15 billion in 2013, the industry employs more than a million Filipinos and is growing at 15 to 20 percent each year.3

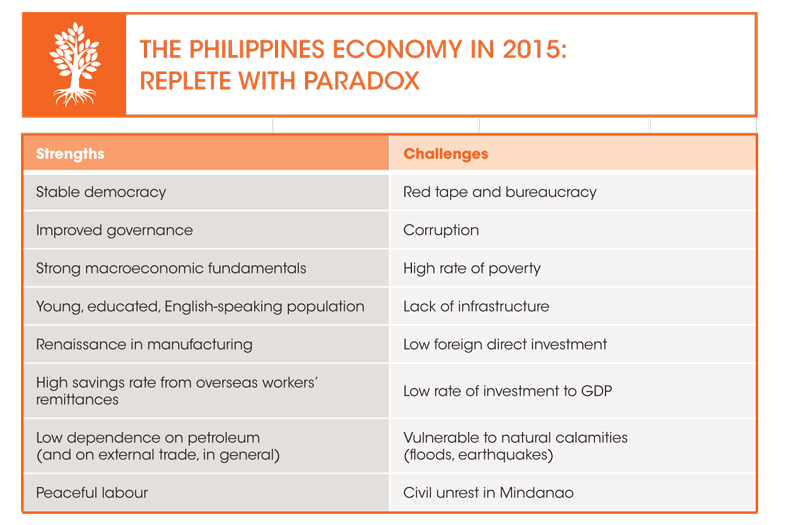

My view is that, while the establishment of the ASEAN economic community is sure to prove mutually beneficial to all member states, political, social, cultural, religious and even economic heterogeneity will call for growth trajectories based on the strengths and challenges unique to each country. The Philippines, too, has to take stock of its competencies and weaknesses—leveraging the former and overcoming the latter—in order to position itself as a strong and stable economy that is open to foreign trade and investment.

Banking on an upwardly mobile workforce

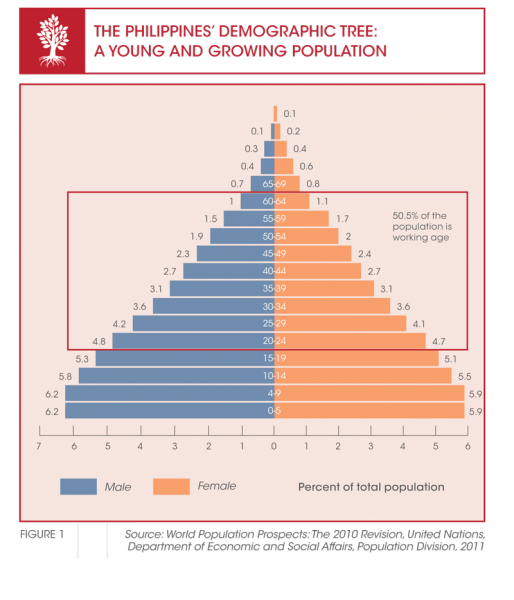

Unlike most developed economies, and many ASEAN countries, the Philippines still has a young and growing population. In 2011, a UN report noted that over half (51 million) of the population was of working age, and only 3.5 percent of the population consisted of aged dependents (refer to Figure 1).

In 2011, a UN report noted that over half (51 million) of the population was of working age.

Investment in education has helped develop the young population into a dominant workforce that is fluent in English, culturally westernised and constantly moving up the workforce value chain. This is a key asset not just for the Philippines but also for ASEAN as a whole. Even though most ASEAN countries are not economically developed, they suffer from developed country demographics. Thailand is a case in point. At US$6,000, Thailand’s annual per capita income is much lower than that of Singapore (which is about US$50,000). Yet its age profile is similar to that of Singapore. Thailand’s birth rate has been declining for almost 30 years. The average age of a farmer in Thailand is 60 years, and few young people want to go into farming. Ageing populations will make it difficult for countries like Thailand to escape the middle income trap.

In 2014, overseas workers accounted for 12 percent of the Philippines’ labour force and contributed US$26 billion to the economy. In fact, remittances from overseas workers are a bigger source of foreign income than tourism. Although domestic workers accounted for 40 percent of total overseas workers in 2012, this profile is rapidly changing as more domestic workers are moving into higher skilled and better paid jobs such as information technology professionals, nurses and caregivers. The trend is apparent in the BPO industry too—the Philippines’ large pool of university graduates is being hired not just to man call centres, but also for data analysis and software development that feeds into the medical, accounting and legal industries in the United States.

Filipinos are sought after by their ASEAN neighbours for key management positions. For over 20 years, Indonesian companies have been importing Filipino managers to head their marketing, finance and accounting functions. In fact, SGV & Co. was instrumental in building Indonesia’s accounting and auditing sector, and many SGV professionals have ascended to top executive positions in numerous Indonesian conglomerates. In addition, there are many American multinationals hiring Filipinos to run operations in Vietnam—although this trend may change in the long term.

The Philippines is also becoming an important player in the region for medical tourism. Filipino doctors that trained and practiced in the U.S. are returning home, setting up state-of-the-art hospitals and attracting patients from all over the world who were earlier looking at Thailand or Singapore as their first choice for medical treatment.

Investment in education has helped the Philippines develop the young population into a dominant workforce that is fluent in English, culturally westernised and constantly moving up the workforce value chain.

Realising the Philippines’ agricultural potential

Up until a decade or so ago, the Philippines’ policy makers largely neglected the agriculture sector. Under the agrarian reforms that started in the 1960s and continued into the mid-1980s, agricultural land was redistributed and divided into small plots, allegedly in the name of social justice. This politically motivated move was disastrous for achieving agricultural efficiency, and only helped to increase the number of landed poor. Most agricultural land in the Philippines, even today, is divided into small plots, which makes it economically inefficient for modern agricultural techniques. This, combined with the government’s tunnel-like focus on industrialisation, has resulted in the lack of rural infrastructure, urban-rural transport networks, irrigation facilities, mechanised farming and modern machinery. In 2013, while 32 percent of the population was engaged in agricultural activities, the sector’s contribution to GDP was a mere 11 percent.4

There is a strong case for investing in and developing agriculture in the Philippines. First, outside of Manila and a handful of other cities, most of the country is rural. For economic growth to be sustainable, it must trickle down to the rural areas. Here, Filipino policy makers can learn a lesson or two from Thailand, a country that has reaped the long-term benefits of investing in agriculture and countryside development. The government in Thailand has indulged its farmers with the necessary infrastructure such as farm-to-market roads, irrigation systems, transport and warehousing facilities—all inputs that make farming profitable.

A productive agriculture sector not only improves the incomes of farming populations–but, in addition, rural prosperity also creates a large domestic market for other goods and services. For example, the Thais have been able to create a domestic market for one million automobiles, much larger than that of the Philippines, which in turn keeps their exports competitive. A similar story is seen in Malaysia, where the palm oil industry has helped steer the nation’s overall economic development (refer to the Box Story below).

So what will happen when commodity trade barriers come down? If Filipino farmers do not improve their productivity, they are sure to lose out as 2015 heralds free trade in commodities in ASEAN. The sugar industry in the Philippines, for example, is trembling in its roots. In Thailand, sugar is produced at one-third the cost of that in the Philippines. Thus far, this industry has survived because of tariff protection. Bringing down the trade barriers may render many sugar-producing regions like Central Luzon and Calabarzon uncompetitive. Multinationals like Coca-Cola and Pepsi would prefer to buy their sugar from Thailand. This may sound ominous, but it is equally a call for change. In the short run, some mills will close down and lose out to foreign competition, but in the medium- to long-run, the sugar industry in the Philippines will restructure and move toward the more efficient model of large-scale estate farming.

Converting savings into investment

In 2012, the Philippines’ investment to GDP ratio was 18 percent, compared to an average investment rate of 30 percent for Singapore and 49 percent for China.5 Despite the reforms of the last 25 years, there are still several provisions in the Philippines’ constitution that discourage foreign direct investment. For instance, foreigners are prohibited from investing in media, and can only hold a 25 percent stake in telecommunications, and a 40 percent stake in public utilities. All these controls stem from nationalistic concerns and sentiments.

So how has the country achieved a 6 to 7 percent growth rate in the past couple of years? The growth has been primarily consumption-led, rather than investment-led. The Philippines has a very high savings rate, mostly owing to the remittances of overseas workers. With US$26 billion being sent by Filipinos abroad every year, the savings rate as a percentage of gross national product was 32 percent in 2014. Yet these savings are not being converted into investments. There is a huge opportunity here, which can be reaped by both domestic and foreign investors.

The growth in the Philippines has been primarily consumption-led, rather than investment-led.

Finding a broader definition of industry

Filipino policy makers have for many years focused on manufacturing as a critical path to industrialisation. But there are four components of industry— mining, manufacturing, construction and public utilities—and over time, this obsession with manufacturing has proved detrimental to the nation’s growth. Countries like Hong Kong and Singapore illustrate that it is possible to be highly industrialised even if manufacturing contributes little to GDP, as long as it has sizeable sectors in construction and public utilities (ie, telecom, water and electricity). For the Philippines, mining, along with its secondary growth effects, can be a major catalyst for industrialisation. It is impossible to extract mineral ores from the earth without adequate roads, power and water facilities, and other infrastructure that are indispensable to mining operations. Any advanced mining operation can transform ‘boondocks’ into a highly ‘industrialised’ zone.

The Philippines is an attractive investment destination due to its low labour costs. But here it faces stiff competition from Vietnam, and possibly Myanmar and Cambodia a few years down the line. Many Japanese companies have transferred their factories to the Philippines because of high labour and energy costs in Japan. Korea is not far behind. Economic integration can provide the much-needed boost to industry. With an aggregate population of 620 million consumers in ASEAN, industries can benefit, especially in the area of contract manufacturing. American and European companies, drawn by low labour costs, can certainly take advantage of this integration.

Some final thoughts for AEC leadership

In my opinion, ASEAN leaders should be mindful of some strategic guidelines as they blaze new trails of regional cooperation. First, the AEC is a work in progress that may take at least 20 years to complete. It took more than 20 years for the European Economic Community (EEC) to be a real union and even now there are some members threatening to secede. On the optimistic side, the AEC as an economic union may be realised faster than the EEC because the 10 member nations are realistic enough not to get side-tracked by any utopian vision of a political union (which has caused a lot of distraction in Europe). Because a political union has been considered farfetched from the beginning, there will be no attempt to have a common fiscal policy and therefore, there is little chance that the AEC will try to create a common currency. To make a monetary union work, there must first be congruence in fiscal policies. This became obvious during the recent economic crisis and recession, when the Eurozone got so much flak because it could not find its way to a solution that was agreeable to all member nations.

Second, there is no such thing as a decoupling of the AEC from the rest of the global economy. Although trade and investment relations among ASEAN countries will grow faster than those with the rest of the world, individually, economies in the AEC will continue to be important trade and investment partners with countries outside of their region. The AEC may also discover major opportunities of linking with other emerging markets like Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Nigeria, Turkey, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Needless to say, China will be a dominant market and a source of foreign investment and income for the AEC. For example, spending by Chinese tourists will soon lead all other nationalities in the AEC.

Third, it will be the private sector, not the governments that will take the lead in making the AEC successful. In fact, I would expect some governments to retrogress by introducing ultra-nationalistic non-tariff barriers. This backtracking should not intimidate the private sector, which should be creative enough to roll with the punches as their predecessor companies have already done. The private sector in the Philippines should put pressure on the government, especially after 2016, to move ahead with the amendment of the restrictive provisions in its Constitution against foreign investments and the subsequent legislation to specify the actual liberalisation measures. In order to compete with its neighbours, the Philippines needs to embark on an ambitious infrastructure development programme, one that can be made possible only through foreign investment in both capital and technology.

The final message to the potential Philippine enterprises venturing into the AEC is that “perfect is the enemy of good”. Do not expect the most ideal investment environment, especially in such countries as Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia. Without throwing caution to the wind, try to be in these countries as early as possible during their developmental or ‘take-off’ stages. To use a cliché, the early bird catches the worm.

The final message to the potential Philippine enterprises venturing into the AEC is that “perfect is the enemy of good”.