Vietnam—with its coast line extending over 3,400 kilometres and comprising thousands of islands—has high development potential. The nation enjoys strong national cohesion and social stability. Despite hosting over 50 ethnic groups, religious and ethnic conflict is not of much concern. Moreover, 65 percent of its population is of working age, there is a high literacy rate, a growing middle class and an attractive domestic market. And yet, I believe that Vietnam has to aggressively continue reforming if it is to achieve its full potential. Vietnam has to restructure its economy—moving to higher value-added products and services, reorganising its institutions, shifting to a genuine meritocracy, and supporting innovation.

An economy in transition

In the last 30 years, Vietnam has undertaken bold reforms to move away from a centrally-planned, Soviet-moulded economic system—one that inhibited the growth of the private sector and tried to centralise every economic activity within the administration. But to understand the Vietnamese economy today, it is important to appreciate the nation’s history.

Vietnam was part of French Indochina from 1887 until France’s 1954 defeat at Dien Bien Phu. Under the 1954 Geneva Accords, the country was divided into the communist North and anti-communist South. In 1975, Vietnam was reunited under communist rule. After re-unification, North Vietnam tried to impose the same socio-economic model on the South, albeit with little success. While central planning was useful during the war, it seemed inefficient in peacetime.

For instance, the socialist view had, at first, collectivised the farms and dictated a fixed price for purchasing crops such as rice. But thereafter, due to soaring inflation, the price soon became less than the cost of production—so the more the farmer produced, the more he lost. As a result, Vietnam began moving from a highly productive agrarian economy to a crop importing one, and the Soviet Union had to provide huge assistance to Vietnam. As per my calculations, the GDP of Vietnam in 1975 was around US$2.5 billion, and Soviet assistance contributed an additional US$2 billion! This created a false sense of economic success for the Vietnamese leadership.

Over the next decade or so, Vietnam experienced little economic growth, largely on account of closed economic policies. But as the Soviet Union began to collapse and its financial assistance dried up, the Vietnamese economy too began to break down as there were insufficient funds to import essential commodities such as oil, fertiliser and steel. In order to survive, the Vietnamese authorities had to shift to a market economy. In 1986, the country introduced the ‘Doi Moi’ or economic renovation policy—a commitment to increased economic liberalisation and structural reforms necessary to modernise the economy.

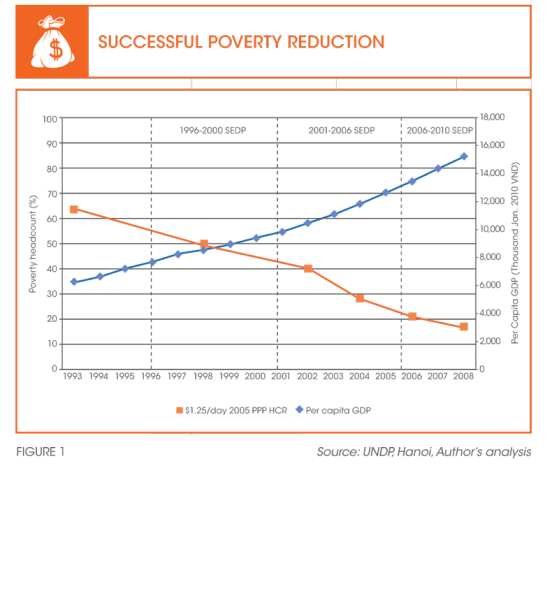

And I believe these reforms have been largely successful. Poverty levels have dropped significantly. At the time of the reforms, over 60 percent of Vietnam was living in poverty (based on the World Bank’s criterion of living on less than US$1.25 per day). But by 2010, this had been reduced to around 12 percent—a truly impressive achievement (refer to Figure 1).

The reforms incentivised the farmers, who were given packages of land to grow their own crops, and to freely sell their product at market prices. This led to an earnings increase of as high as 150 to 300 percent over the two decades since Doi Moi was introduced. Vietnam was transformed from a crop importer to an exporter of rice, fish, cashews, black pepper, coffee and others. So in the agricultural sector, the success story has been quite obvious.

As for industry, the government has been promoting private sector development by making it easier to do business. Let me give an example. Prior to 1999, a businessman would need to provide a plethora of documents and get permission from the chairman of a province before commencing an enterprise. The model was similar to the Company Law followed by France and was a great impediment to the development of the private sector. But in 1999, while I was the head of the Central Institute of Economic Management, we conducted a study and found that there were more than 300 licences and permits—most of which did nothing other than producing unnecessary bureaucratic burden. Since then, we have assisted the prime minister in cancelling 286 such licenses. Some of these were replaced by ‘business conditions’. So for instance, if you wanted to open a gasoline station, a condition would necessitate the acquisition of a permit concerning fire and environmental protection. The condition clearly lays out what materials need to be submitted to the authorities in order to obtain the necessary permission, and officials have little scope to harass applicants for additional documents. Hence, we successfully introduced a very liberal Enterprise Law, and I believe this has contributed immensely to the growth in Vietnam’s economy—in both the agricultural and private sectors.

GDP GROWTH

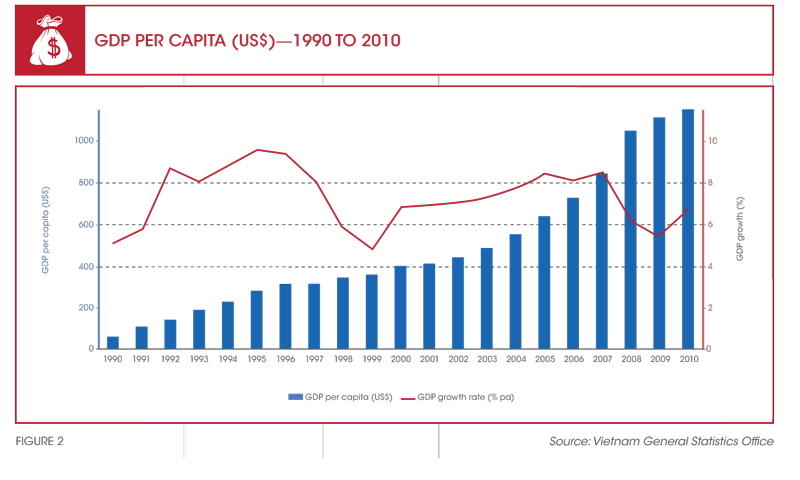

1997-98 was the time of the Asian Financial Crisis, and the per capita GDP growth rate began to slow (refer to Figure 2).

In 2007, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization, which provided a boost to the reform drive. Subsequently, there was a huge inflow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the securities market. The government also began allowing state-owned companies to diversify their investments. Authority was further decentralised from the centre to the provinces, and was combined with a system to measure provincial performance based on GDP growth. The provinces found that the easiest way to increase GDP was to sell land. Consequently, minerals and forestry were commercialised, and the provinces soon began competing to attract foreign investment—instead of investing in science, technology and developing human capital. There was a push for easy money to speculate in real estate and securities. As a result, 2008-09 became a period of soaring inflation—during a real estate bubble, prices went up by as much as ten times. By 2011, inflation had reached 23 percent.

The government had to reduce the money supply and credit supply to cool the economy, and in February 2011, it focused its policies towards stabilising the economy, rather than striving for higher economic growth, which had fuelled inflation.

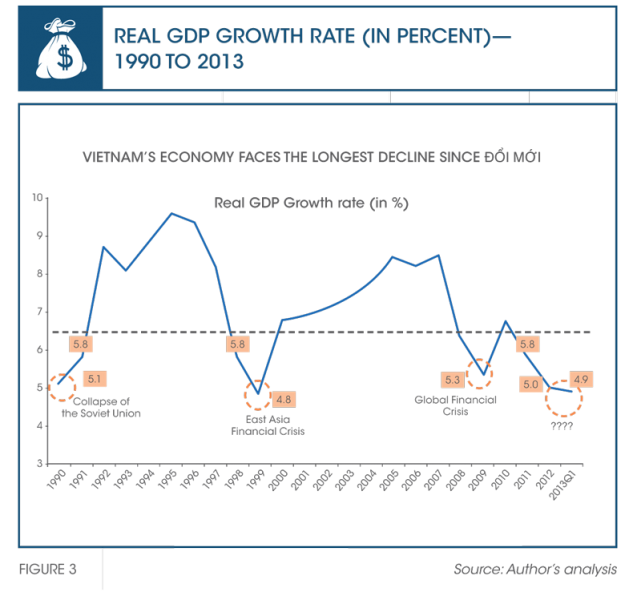

The economy has since recovered—but is still below its past 10-year average. Today, Vietnam’s economy faces a secular decline in growth rates (refer to Figure 3).

There is now an urgency to continue on the reform path—externally integrating with the rest of the world, and internally to make it easier to do business.

Bold measures to integrate with the world

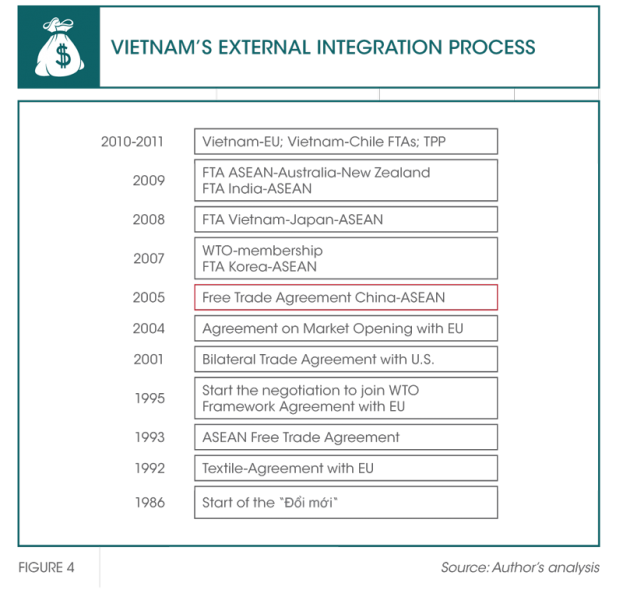

Vietnam’s integration with the rest of the world is so far impressive. It has joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), signed bilateral trade agreements with the U.S. and several other countries (refer to Figure 4), and is now negotiating to join the TransPacific Partnership (TPP).1 If all goes well, Vietnam will soon have signed free trade agreements with 55 economies in the world—making it a pioneer in integration.

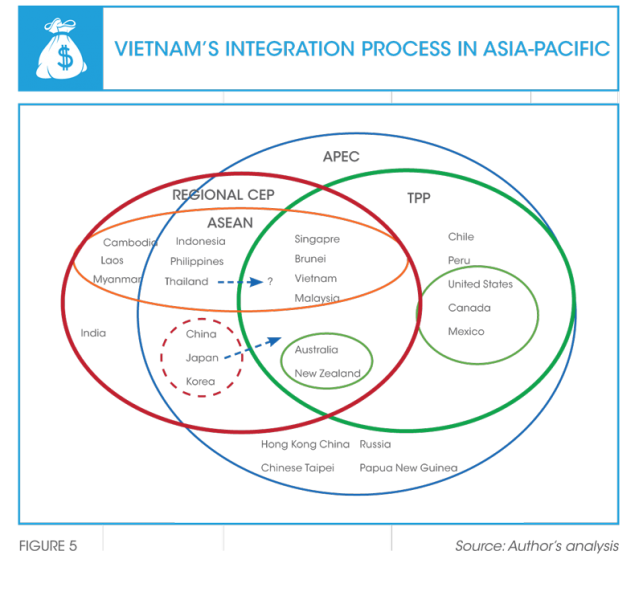

Overall, Vietnam can expect to earn some additional GDP growth from the TPP and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), while the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)2 will result in tough competition with China. Figure 5 shows the agenda of the integration process in times to come.

In my opinion, Vietnam will benefit more from the TPP than from the AEC. Being a primarily agrarian economy, Vietnam will compete with all the AEC member countries, with the exception of Singapore. It will have to compete with Thailand on farm products, with Cambodia on garments, and with Indonesia on cars. But if Vietnam joins the TPP, it will enjoy complementary efficiencies with many more advanced economies such as the U.S., Japan and Chile. Exports of products, such as rice to the U.S., are expected to rise exponentially once tariff rates drop to zero post-TPP. Many of Vietnam’s competitors are outside the TPP, giving the country considerable trade advantage (refer to Figure 5). Hence Vietnam’s eagerness to sign the TPP and restructure its economy so that it can be prepared for future competition, and benefit from the common market and lower restrictions on movement of labour.

Internal reforms, making it easier to do business, are a must

If we review the World Bank report for ease of doing business (benchmarked to June 2014), it becomes apparent that there is a long way to go. Out of the 189 countries in the report, Vietnam is ranked 78 overall.

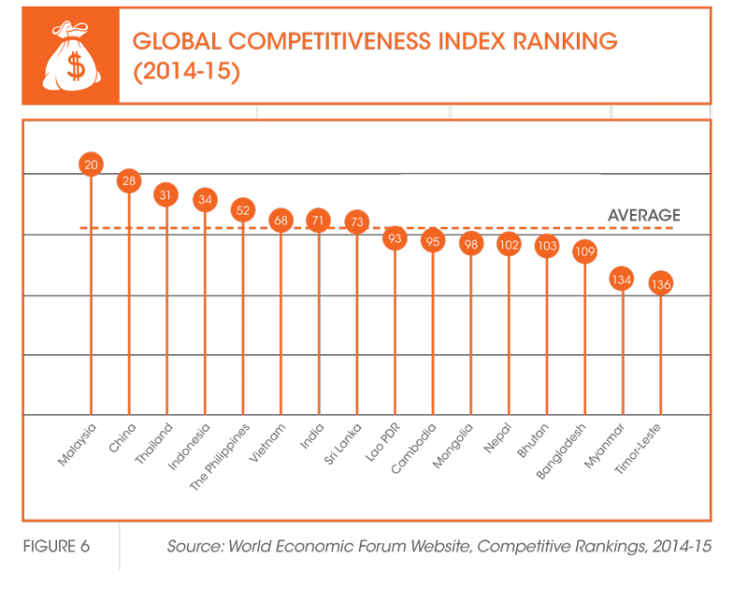

Similarly, on the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index for 2014-2015, Vietnam is ranked 68 out of 144 economies, after its neighbours Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia (refer to Figure 6).

Hence there is much room for improvement, and Vietnam needs to continue its reforms, or else it faces the risk of falling into the middle-income trap, where productivity falls behind rising earnings and costs.

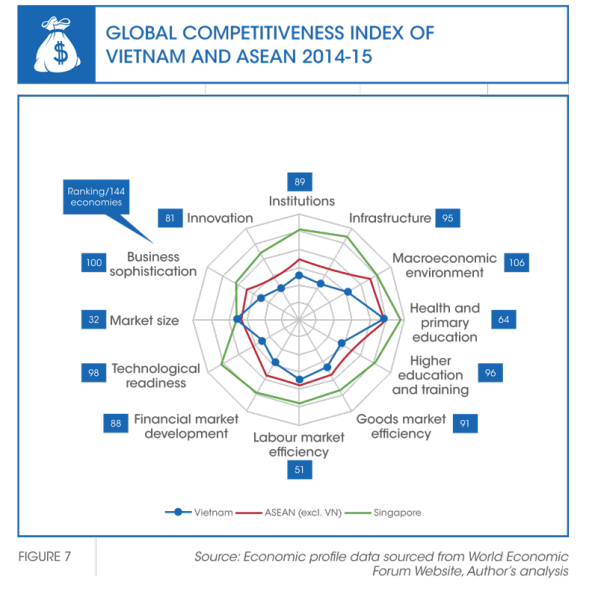

If we look specifically within ASEAN (refer to Figure 7), the global competitive index of Singapore is the best. Vietnam has advantages in terms of its market size, health and primary education, and labour market efficiency—but suffers from infrastructure issues, and deficiencies in higher education, technical readiness and business sophistication.

In the past, the government did not want to recognise the relevancy of these rankings and insisted on producing their own rankings to convince themselves that the results were good. But they have now publicly accepted the World Bank and WEF rankings, and issued Resolution 19—a policy to improve competitiveness and reduce the ranking gap between Vietnam and the ASEAN-6.3

The intention and determination is welcome—but how can the public institutions be reformed such that they become less of an administrative body and more of a cooperative, pro-business development body? How can the bureaucracy be pushed to promote innovation and motivate businesses to invest in science and technology?

What must be done next?

The situation in Vietnam is quite challenging. Economic growth is still based on resource-related industries and low value-added processing. Labour costs remain low (monthly pay for manufacturing workers in Vietnam is roughly 43 percent of that in China4), so the economy is currently competitive and FDI is flowing in.

However, Vietnam must move from a low-wage economy to one that comprises a highly skilled, well-trained and sophisticated labour force. Samsung is an example of a corporation successfully tapping Vietnam’s potential. Vietnam is their largest manufacturing centre in the world, and the company has also established an R&D centre here. Recently Samsung called for 170 supporting products and services to be provided from Vietnam. About 1,000 Vietnamese companies applied to be part of the initiative, but only 12 were selected, and each needs to invest around US$12-15 million to modernise their plants. While these companies can produce what Samsung requires, their costs are too high owing to their manual processes, and so they must implement automatic systems in order to improve productivity. Although foreign-invested sectors accounted for about 70 percent of Vietnam’s total exports, they remained limited added value.

To attract more global production, Southeast Asia must raise labour productivity. A McKinsey report put the annual manufacturing output per worker in 2012 at US$3,800 in Vietnam, as compared to US$14,200 in Indonesia, US$21,200 in Thailand, US$33,200 in Malaysia and US$57,100 in China. For companies looking to set up shop, these statistics negate any advantage of cheap labour that Vietnam may have to offer. One of the main reasons that labour productivity in Vietnam is so low is because the share of agricultural and informal household industries is still very high, at 20 percent and 30 percent of output respectively. Moreover, informal households are not very competitive as they lack access to capital for investing in training or IT, and pay little adherence to corporate governance. Vietnam must turn these households into a registered formal private sector (which only makes up 12 percent of industry), and also develop agriculture to accommodate large-scale production.

Moreover, Vietnamese businesses must be linked to the global value chain. Vietnam has been quickly integrating into the world economy, but has not joined the value chain. For example, the country exports fish, but not fish-derived products. So the problem is now to reorganise the economy such that the agenda in Vietnam is not only institutional and market reforms, but also policies aimed at restructuring the economy. If Vietnam wants to truly prosper, the country must transition from a low labour cost economy to one based on science and technology in order to produce high-value products and services. The farmers must be trained, organised and equipped to capture economies of scale and move up the value chain. Policymakers must accept market discipline and stand by their commitments.

Similarly, I believe that international integration, including that with the AEC, will be the necessary external pressure that pushes for internal restructuring and reform in Vietnam. And it will apply not only to the public institutions, but also to every sector and society as a whole. We are talking not only about education, but also say, vocational training or any other imaginable mechanism to further develop human capital.

The Vietnamese government has recognised the problem and shown determination to deal with it—as it looks at streamlining the bureaucracy and improving the role of civil society and that of responsible mass media, which can act as a constructive and yet critical counterpart of government. Social media and mobile connectivity is another channel that is key to democratising and creating these kinds of discussions. Especially when one considers Vietnam’s 34 million and growing Facebook users who typically access the network via their smartphones.

Vietnamese businesses must be linked to the global value chain.

Optimism for the future

If one looks at other transition economies such as Mongolia and Cuba, it becomes apparent that Vietnam is relatively advanced in terms of implementing internal reforms and integrating with the rest of the world. Further integration will require new standards on fair competition and transparency from the government.

If you look at Vietnam’s history, reform was the product of a survival strategy. Vietnam is still a one-party communist country, and there continues to be a debate on how people can raise their voice and contribute to the reform of institutions, improving transparency, openness and accountability. Reform has been a gradual process—one of learning by doing. But we cannot relax. Economic growth is stagnating and Vietnam is growing below its potential. Restructuring and reform of the economy must be urgently implemented.

I am optimistic about the future, and believe that if Vietnam can ignite the creativity and dynamism of its people, miracles can be achieved. There are many excellent people in the business community here, and if there is a restructuring of the business process, monitoring of monopolies and controlling of vested interest groups, Vietnam should be well set to prosper and take great advantage of its integration into the world economy.

Economic growth is stagnating, and Vietnam is growing below its potential. Restructuring and reform of the economy must be urgently implemented.