Despite the newfangled business models and market game changers, the old axiom of industry continues to ring true: leadership matters.

While innovation continues to rest on the successful commercialisation of an idea, businesses today are subject to an ever-evolving techno-economic paradigm driven by the application of new information and communication technologies (ICT). Time and again, the originator of an invention, or idea, fails to capitalise on its inherent value because innovation is not so much about generating ideas and developing new products or services, but about problem-solving. And successful innovation depends on how fi rms identify and prioritise which problems need to be solved.

Opportunities often arise in the variation of cost to innovation, meaning that opportunities to innovate are found within an organisation’s unique capabilities, capacity and position in the market. It is within these factors that we defi ne innovation as a better means to serve the specifi c needs of one’s customer base and expand that base, or develop superior ways of catering to someone else’s needs.

These opportunities are often fleeting. A firm that was once the disruptor may eventually find itself the disrupted. Leaders of incumbent firms can avoid disruption by recognising where they might be exposed to it, and in the process, astutely select and prioritise the ‘right kind’ of problems to be solved—not a simple task.

However, understanding innovation through the lens of a firm’s variation of cost can help leaders manage innovation and growth. Leaders should focus on innovation strategies that capitalise and expand on opportunities adjacent to a firm’s existing core output of products and services, while also recognising that the successful execution of these strategies requires the right kind of organisational behaviours, structures and culture.

Recognising opportunity

Firms often overlook opportunities because they are too burdened by the day-to-day, becoming inwardly focused as they forget to make time to be forward thinking. Firms may persist in this mindset until their market position erodes overnight, leaving them open to more opportunistic innovators. This is oftentimes a failure to understand the changing needs of their customer base. But even beyond the customer, fi rms must examine their entire channel structure, and evaluate their position in the market and how they (and their network of providers) might be impacted by change.

Whether consumer facing or business facing, innovation is ultimately about solving problems. In a commercial sense, it is about how firms do business and make money. It should come as no surprise that disruptive innovations are often commercialised in emerging and traditionally insignificant markets. Products and services catering to these markets must be profitable at lower margins; they must be simpler or cheaper to produce. This is essentially an evolutionary and timeless phenomenon.

We can draw on the early PC industry as an example where proto-PCs were initially targeted towards hobbyists and the home video game console market before eventually going mainstream—taking the business world by storm, and in the process, burying mainframe companies like Amdahl and Unisys. A similar usurpation is taking place today.

FinTech companies are chipping away at the periphery of the traditional banking sector by offering services such as payments and low-cost alternative solutions to cross-border remittances; an essential service to migrant workers. Offering such services is not nearly as lucrative for traditional, incumbent banks as providing services to their more established and less risky customer base. But these overlooked markets may yield dividends for established firms if they can expand their core products and services into adjacent areas in innovative ways. DBS Bank in Singapore, for example, is digitising its backend and collaborating with Singtel, a Singaporebased telecommunications giant, to offer banking services like PayLah!, a mobile payments and deposits platform. It is through partnerships and digital investments such as these, which leverage existing competencies, channels and value networks, that large and established firms can adapt to disruption.

Disruptive versus sustaining innovation

Innovative products may also introduce a new dimension of performance—or answer a previously unmet or undermet want or need. All this can be accomplished through new business models, new manufacturing techniques, new products and services, or different ways of offering established products and services.

DISRUPTIVE INNOVATION

Disruptors, unlike incumbents, are uninhibited by legacy structures because they don’t have a customer base to fulfil, and so can focus on something very specific, unproven and high-risk. This form of innovation often typically comes from the outside. Products and services emanating from this domain are frequently inferior in one respect— but offer some other benefits, such as simplicity, cost and convenience, that appeal to less demanding but underserved consumers. New entrants typically win at this game because they lack an existing customer base to satisfy and serve markets that are low-margin, small or uncertain. At the same time, they are not wedded to large capital investments and infrastructure.

That said, incumbent firms need not be fatalistic. Such disruption is only one aspect of one type of innovation. Managers need to redefi ne what innovation means to them and how it applies to their business. This goes beyond lip service. Innovation, after all, is more than a buzzword—and it is a cliché to think of all innovation as disruptive innovation.

SUSTAINING INNOVATION

Sustaining innovation—as in the structured iterative approach towards improving and safeguarding existing capabilities—is a proven strategy that nourishes one’s position within an industry ecosystem or value network. For example, IBM has, for generations, transitioned its product and service offerings in step with the evolving needs of its client business community. In fact, it has gone a step further and even redefi ned their needs. This strategy is also reflective of the risk appetite of successful incumbent firms in general. Whereas start-ups are by defi nition high risk and high reward, established firms must take into consideration stakeholder responsibilities that require a more balanced strategy. Rather than pushing the industry to the edge in a drive for game-changing innovation, the incumbent firm typically relies on a best practices method of management.

They do what they have always done, what is prescribed, what reinforces their competencies, and incrementally invest in innovation as a way to expand their ‘sweet spot’ or core offerings—that is, they look for opportunities in their variation of cost. In IBM’s case, it was always about providing services that help their business-facing customers work more productively. Whether it was manufacturing mainframes in the 1970s, the iconic Model M keyboard in the PC era, or high-end knowledge and pattern recognition services through today’s Watson—IBM’s core offerings always remained ‘business tools’.

Competency destroying and competency enhancing

Investing in innovation can be thought of categorically: competency destroying and competency enhancing.

Competency destroying innovation improves performance in a new dimension; these are the game changers. A recent example would be the rise of Uber’s ride-sharing technology.

By integrating multiple mobile technologies embedded in smartphones through sophisticated programming, Uber is able to offer taxi services with greater convenience and at a lower operational cost than incumbent firms. Essentially offering an under-met service through a scalable business model built on top of a mobile app, it empowers anyone with a car to offer taxi services to anyone with a smartphone through the Uber app. Whether Uber or FinTech, the lesson here is that any product or service that can be digitised, will be digitised, and disrupted. So, what are the next big competency destroying innovations? Self-driving cars? Regenerative medicine? In all likelihood, the firm that unleashes the next big disruption will probably be an unknown.

Competency enhancing innovations, on the other hand, are more iterative. This type of innovation improves performance along an existing dimension. For example, the transition from CDs to DVDs or mechanical to electric typewriters; in both instances the underlying technology is relatively unchanged, just upgraded. The reason for this is that fi rms embrace their existing competencies, and sustaining innovations complement this because they fit within existing organisational and capital structures. An installed base is a far less risky way to innovate. Moreover, firms with an installed base also face an inertia from previous investments catering to their customer base, as well as broader clients throughout their value network.

Leaders of incumbent firms should focus on incubating competency enhancing innovations for the short- to medium-term and competency destroying innovations for the longerterm—insofar as they are aligned to what the firm already does (however, this does not mean that the firm should remain ‘locked’ within the same industry or customer base).

In the insurance industry, companies like Aviva in the U.K. or NTUC Income in Singapore have partnered with tech accelerators to improve profitability in low margin and low growth markets. Meanwhile telematics policies, such as real time monitoring of vehicles for example, could generate enormous premiums and reduce risk profiles, even in high-risk car insurance markets like Russia.

However, innovation need not come only from start-ups or large established firms. Institutions and governments should also pursue an innovation policy. India is a notable example of such innovation. The country is in the process of issuing each of its citizens an ‘Aadhar’ card, a unique 12-digit PIN identity based on their biometric and demographic data. As of January 2017, this card has been issued to 1.11 billion residents of India. The Aadhar card qualifi es as a valid identity for accessing several government services, such as receiving subsidised fuel from the public distribution system or opening a bank account. The innovation has had a cascading effect, coming as a boon to several other industries. A case in point is India’s peer-to-peer payments industry, which is booming and providing an opportunity for many upstarts to enter this FinTech space.

Building innovative behaviours, structures and culture

So what can a leader do to recognise and capture the opportunities to innovate?

LOOK BEYOND YOUR ORGANISATION AND INDUSTRY

Industry boundaries are breaking down, and current competitors may not be future competitors. This requires incumbent firms to look beyond their own organisation and industry to see both opportunity and threat. Incumbent firms must establish frameworks to anticipate disruptive innovation—particularly if there are any elements to their products and services that can be digitised, disintermediated and dematerialised, à la Uber.

Leaders of established and incumbent firms should look to collaboration and partnerships, not only with other industry leaders, but small upstarts as well. This is useful in terms of ‘problem revealing’ as well as ‘solution revealing’. Take Web 2.0 for example, which was ushered in by organisations that facilitate mass collaboration through open platforms and sharing protocols. Open source software, social media, crowdfunding, multiplayer online games and social production have created extraordinary value. Although Web 2.0 organisations have wrought much disruption, firms that ‘stay connected’, share information and collaborate have a better chance of understanding and adapting to new realities such as these, as and when they emerge.

DISRUPT YOURSELF

Firms can stay ahead of disruption by ‘disrupting themselves’. Leaders should facilitate discussions that expose assumptions on misguided views they may have about the market and their customer base. Keep in mind that needs change over time. This is true of one’s customer base and the broader value network that a firm is a part of. Some of the most disastrous mistakes incumbent firms have made in the past is the adoption of certain technologies as just a fad. Just as some may have balked at the idea of talking in pictures at the end of the silent film era, others have underestimated and ignored the power of social media today.

Leaders, however, cannot expect their employees to ‘go out on a limb’ and question assumptions, or take up the mantle of any kind of culture change, without the right kind of incentives. Indeed, aspiration and adaptation are both incentive driven. It is well known that Google, for example, allows its employees to spend as much as 20 percent of their time pursuing their own projects or collaborating with other employees on projects. Developing successful collaborations designed to identify and solve problems in innovative ways require incentives as well. This can take the form of shared intellectual property rights, market entry, or other forms of co-profitability.

UNDERSTAND YOUR CUSTOMER

Social media is creating a convergence between customer service and marketing. Many firms are embracing social media to gauge consumer sentiment and deploy data analytics to better understand customer insight and make informed decisions. Lenovo, a PC, smartphone and tablet manufacturer, is working with Socialbakers, a Czech IT company offering social media analytics software-as-a-service platform, to create executive dashboards that make use of social media data to help drive company decision-making. In doing so, companies like Lenovo are better able to sense consumer trends before their competitors and also serve their customers in more meaningful ways.

Lenovo has concurrently partnered with the Economic Development Board of Singapore to launch its global analytics hub in the island city-state. In exchange for offering incentives for Lenovo to base its analytics hub in Singapore, Singapore gains by bringing in new economic growth drivers and broader network effects. Again, it is these kinds of collaborative efforts and partnerships, underlined by incentives that are becoming increasingly characteristic of organisations operating at the cutting-edge.

RE-EVALUATE THE IT FUNCTION

IT touches all areas of an organisation; this is in fact one of the main reasons why ICT is a prime driver of both sustaining and disruptive innovation. Incumbents must therefore constantly re-evaluate their IT functions in so far as it enables them to take advantage of technology-based initiatives, such as social media marketing, data analytics and cloud-based collaboration tools. At the same time, IT should support the core functions of the firm, not the other way around.

Leaders must ask if there is any aspect of the organisation that can be improved with the right set of IT-related skills and digital infrastructure. This has a direct bearing on not becoming inundated with legacy systems and minimising overheads if properly deployed. But beware of IT pitfalls. If incumbent leaders treat social media as a ‘thing we have to do’, or look at data capabilities as ‘an investment we have to make’, then these new opportunities are never truly embraced.

DON’T IGNORE WHAT YOU ARE GOOD AT

Incumbent firms should innovate on what is familiar by framing the problem within their core competencies. This goes back to the firm’s variation of cost and the pursuit of competency enhancing innovation, namely pursuing innovation that is aligned to organisational competency and the target customer base.

An internal culture of sharing needs to be complemented with an openness to ideas from both an inside-out and outside-in approach to encourage exploration and incorporate the ‘unfamiliar’—in other words, learning to share and being more open. Again, the right kinds of incentives would need to be put in place to foster this kind of culture. Moreover, these incentives cannot be based purely on providing monetary compensation for taking part in innovation. In fact, when money is involved, it often opens the door for infighting. The point is that these incentives should be aligned with ‘trust building’.

Besides encouraging a culture of sharing and collaboration, leaders are also responsible for facilitating what problems should be prioritised and targeted for researching and developing innovative solutions, that is, strategic attentiveness. This should lead to more accurate assessments of the potential threat to one’s existing business, or the chances of success for a new business proposition. However, internal collaboration and external selective sharing and revealing are not enough to drive the necessary insights required for problem identification and problem-solving selection.

TURN ALL YOUR EMPLOYEES INTO DATA SCIENTISTS

Data analytics should be deployed olistically across all levels of the organisation to reveal insights and to avoid being blindsided. This, of course, requires regular and timely investments into information-processing capabilities and proper staffing. UPS, for example, uses its Orion computer platform to turn each of its drivers into a responsive logistical node, where each driver collects extraordinary amounts of data that are used to optimise delivery. And as all the drivers are connected to a network, their routes can be optimised on the fly. With this level of sensory input and response at every level of its logistical network, UPS is able to recognise problems in real-time and prioritise accordingly.

DON’T STOP

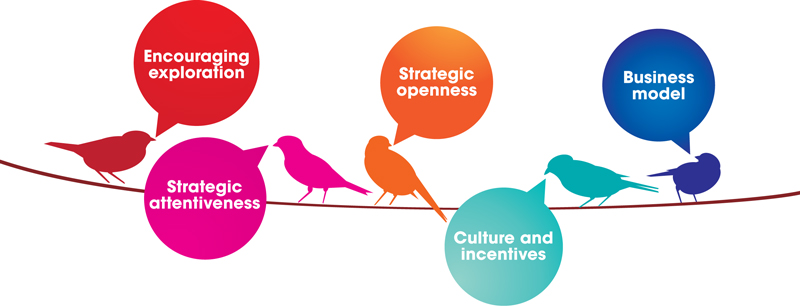

Change is the new normal; staying idle is not an option. Realistically appraise how your company is doing. Leadership matters, but you can’t will innovation into happening. Instead ask yourself, how do you fare as a leader when it comes to:

• Encouraging exploration: How do you combine the familiar with the unfamiliar?

• Strategic attentiveness: How selective is your attention on problem-solving?

• Strategic openness: How do you strategise for sharing and revealing?

• Culture and incentives: Are you building a change culture?

• Business model: How often do you rethink how your business model will adapt to disruption?

Innovation has to be nurtured—encourage your employees to seek out ‘disrupting innovation’ to stay ahead of the game in the long run, but develop ‘sustaining innovation’ to tide you through the short- and the medium-term and help anticipate what direction the disruption will come from.

The important thing is to welcome innovation, in whatever form it takes. There may be organisational structures and processes in place, but they should be tools and not hindrances, and there should be a spirit of innovation that even the largest, most established companies should honour if they hope to survive the next round of disruption.

Gerard George

is Dean of the Lee Kong Chian School of Business and the Lee Kong Chian Chair Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Singapore Management University