Emerging nations need national champions, and national champions need strong support from the state.

A few years ago when we were researching the emergence of Asian brands, we decided to ask a few western friends if they could recall the Haier brand and its products. The answer was no. This surprised me, especially as the Chinese multinational is the world’s number one white goods manufacturer. an indigenous Chinese brand, the Haier story reflects the westward migration of Chinese products, which is currently taking place hand in hand with the migration eastward of some of the developed world’s most iconic brands.

Not so long ago, the so-called developed countries accounted for more than 80 percent of world GDP. Global brands were exclusively from the West. If, in 1990, emerging markets together accounted for 20 percent of global output, by 2010 this had doubled to 40 percent. and in 2013, it had exceeded that of the developed countries. Today emerging markets account for more than 75 percent of mobile phone subscriptions, 75 percent of steel consumption, 25 percent of financial assets worldwide and 75 percent of foreign exchange reserves, among other indicators. Little wonder then that western corporations are in hot pursuit of new business in those regions.

The once hunted have now become hunters. in fact, the emerging markets, especially China and India, have been snapping up western brands for more than 15 years. Couturier Valentino was acquired by the Qatari royal family in 2012, while Aston Martin went to Kuwait in 2007. China now owns the glorious motoring brands of Saab (2011), Volvo (2010) and Mg rover (2005), just as India in 2008 acquired Jaguar and Land rover. To say nothing of Ferretti Yachts, acquired by China’s Weichai group in 2012, or new York’s Pierre Hotel, acquired by the Taj group in 2005. Tetley Tea also went to India in 2000.

Emerging markets, especially China and India, have been snapping up western brands for more than 15 years.

National champions

However, acquisition is only one of several means used by companies from emerging markets, not just China, as they trawl for global opportunities to expand beyond their local geographies. In our book Brand Breakout: How Emerging Market Brands Will Go Global, we advocate eight strategies for building brands—such as the ‘Asian Tortoise’ route of migrating to higher quality and brand premium; the ‘diaspora’ route of following emigrants and tourists by tapping into ethnic affirmation and bi-culturalism segments; or then the ‘Cultural resources’ route by focusing on the rituals and values a nation is renowned for.

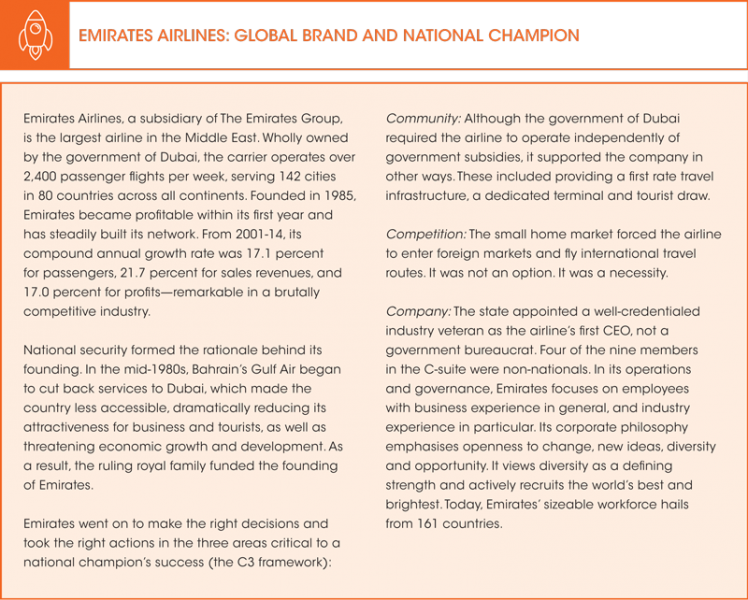

In this article, we focus on the ‘national Champions’ route, as it is particularly germane to this region’s emerging markets and their current state of development. as the name suggests, a national champion is a business enterprise selected by the government of a nation-state to spearhead its national effort in competing internationally in a particular industry, which could be natural resources, basic industries, intermediate goods, energy, consumer products, advanced technology, or services. The champion receives special treatment from the government, including subsidies, market protection in the form of tariffs and import restrictions, and firm-specific or industry-specific policies that foster its growth.

CREATING NATIONAL CHAMPIONS

The industrial policy rationale holds that certain sectors of the home economy are particularly valuable because they provide high-paying jobs and/or carry out high value-added business activities. Unless a country wants to remain a collection of screwdriver factories, the government must actively nurture home-grown firms. Tweaking industrial policy appeals to emerging markets that want their industries to grow in sophistication in the long term. China and India both use industrial policies to promote their national champions.

The strategic trade rationale argues that the state should maintain a home-grown presence in sectors where economies of scale are exceptionally large (often larger than the ability of any single national market to absorb output efficiently), barriers to entry are especially high, and rent-seeking behaviour is prevalent. Without state help, such sectors are subject to pre-exemption from other restrictions that would otherwise be imposed on foreign firms or rival states.

Meanwhile the national security rationale holds that countries must avoid dependence on foreign firms that might delay, deny, or constrain the provision of goods and services crucial for the proper functioning of the home economy or its security apparatus. Emerging markets do not want foreigners to control the supply and utilisation of their native resources such as energy and metals. For this reason, we find the largest national champions in extractive industrials, such as Coal India, Russia’s Gazprom, the world’s largest natural gas company, and Brazil’s copper extraction firm, Vale. Such industries are considered to be fundamental to a country’s sovereignty, wealth, security and development.

Governments usually advocate the creation of national champions on the basis of industrial, strategic trade and national security policies.

NOT ALWAYS A CHAMPION?

National champions have their limitations. Preferential treatment may be so strong that it stifles the competitive rivalry that is necessary for continuous product improvement and the development of brands vital for survival in the global marketplace. national champions may also devour more resources than a more efficient private firm. And finally, the politically-driven process typically favours well-connected insiders over innovative outsiders.

There are also limitations on the ability of government bureaucrats to choose wisely, be it technology or staff. As a result, many national champions perform poorly. Some are more properly considered national basket cases rather than national breadwinners!

As the importance of a firm’s nationality may diminish over time when it becomes multinational or globalised, the leaders of national champions may lose their ability or willingness to respond to the needs of local politicians where such a response might run contrary to corporate self-interest or sound business principles.

Building National Brands

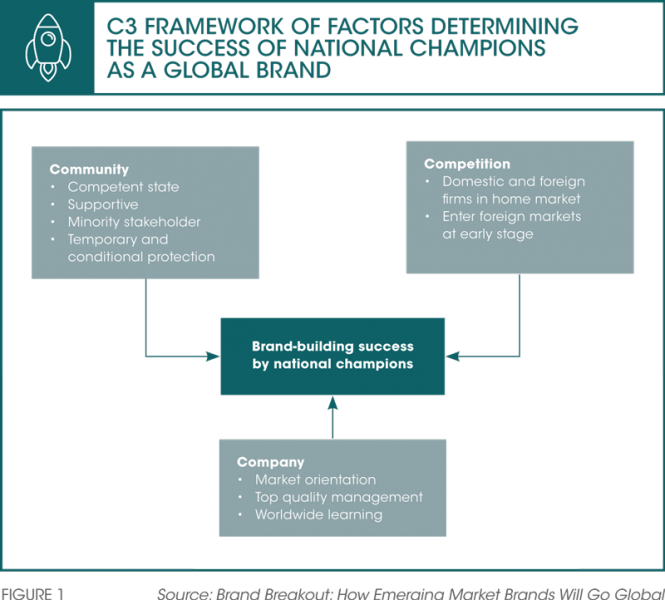

Successful national champions need certain key characteristics to build strong consumer brands. a state can successfully incubate national champions into global brands, provided that government leaders consider three conditions—company, community, and competition (refer to Figure 1). We call this the ‘C3 Framework’.

In the C-suite, there should be an emphasis on competence rather than political appointments, or the ‘politics of patronage’.

COMPANY

National champions frequently struggle to build strong brands as they lack a customer-based approach. Public policy-makers thus need to ensure that every national champion is empowered to orient its efforts to market needs, not political or product ambitions. As Ajit Singh, india’s civil aviation minister charged with the turnaround of Air India, observed, “It is very difficult for the government to run any service sector business. For government employees, they are the kings; the customer is never the king.”1

Meanwhile in the C-suite, there should be an emphasis on competence rather than political appointments, or the ‘politics of patronage’. Along with business competence, national champions should be striving for worldwide learning, rather than having the ‘home market knows best’ attitude. The hiring of world-class global talent and leveraging integrated organisational learning processes that promote worldwide learning, rather than a home-centric view of the world, are vital preconditions for developing brand-building capabilities.

Finally, acceleration of the learning process on a worldwide scale is needed. Here various means are possible, including the acquisition of foreign companies to gain rare technological and brand-building expertise, rather than organic learning which could take many years. another is the listing of the company on foreign exchanges, which introduces the brand to the world’s most sophisticated bankers and analysts, and helps to attract foreign talent from the best business schools to influence the corporate culture and people.

The state needs to support, rather than direct, business activities.

COMMUNITY

The state can play a positive role in the business community by helping to launch healthy national champions that are able to develop global capabilities. But public policy makers must also do their best to root out incompetence, corruption and cronyism. Competency in this context means being manned by highly educated bureaucrats who operate consistently and predictably, with openness and transparency, accountability, and honesty in decision-making and execution.

The state needs to support, rather than direct, business activities. This entails the setting up of economic and knowledge infrastructures in which national champions can seed and flourish. A supportive economic infrastructure is capable of protecting national champions for a short time against foreign encroachment, through subsidising R&D and financing state purchases. For national champions to be able to compete globally on quality, rather than price, the state must cultivate scientists, technologists and engineers to conduct first-rate R&D.

Ideally, the state will be restricted to a minority shareholding, which limits its ability to use national champions for rewarding clients or pursuing social policies. Pioneered in Brazil, the minority-shareholder model provides private investors with just enough power to insist on greater operational efficiency and managerial effectiveness. Further, by taking a minority stake, the state can assist more companies with the same amount of resources.

State support needs to be short-term and conditional on set market-based performance measures, rather than offering permanent and unlimited protection. Without clear limits on the duration and nature of state support, the company will never learn to compete. Market-based performance metrics force the company to focus on its customers, as well as its bureaucratic owners.

COMPETITION

Firms sharpen their skills by competing both in their home market and abroad. This means a focus on home market rivalry, rather than support for a quasi-monopoly. Monopolies breed complacency and stifle innovation. if a firm does not learn to stand on its merits, it has little chance of survival outside the home market.

Home market rivalry thus needs to be fostered. industry boundaries no longer stop at national borders. Foreign market entry should be stimulated to enable national champions to improve their skills through competition. The earlier the national champion faces the rigours of global competition, the better it will adapt its operations for the market and adopt a customer-based brand-building approach.

Country-of-origin: An asset or a liability?

A nation’s image is built gradually over time. Surprisingly, more than a few developed countries, including Germany, Japan and, until recently, South Korea, have had negative connotations associated with their image in the past. Centuries earlier, it took several attempts before German craftsmen were able to produce porcelain equivalent to that made in China, thereby establishing the now famous Meissen porcelain factory. Until as late as the 1970s, Japanese brands were synonymous with imitations and shoddy quality. That changed with the introduction of high quality vehicles at a competitive price. Then, as Japan moved up the quality chain, South Korea took over low-end manufacturing, and has now moved forward as a leader in electronics and cosmetics.

Historically there is no precedent of a country evolving into a developed economy without having some global brands emerge from it. Generally speaking, products from developed countries continue to have a high-quality image, whereas those hailing from India, China or Russia mostly decrease a brand’s equity.

Yet consumer perceptions are known to lag behind reality, which means that one of the biggest challenges many emerging markets face as they globalise is the perception that their brands are inferior. So why do consumers care about a brand’s country-of-origin when they can evaluate the product on its own merits and act accordingly? The answer is that, for whatever reason, most consumers are either unwilling or unable to make an assessment as they lack the capabilities to analyse the information. instead, they rely on ‘cues’ that, in their perception, reveal something about the qualities of the product. These include its brand name and country of origin.

Four factors are associated with the image of a country: its economic development (which reflects its ability to manufacture), its culture and heritage, governance-related issues, and its people. in particular, lack of good governance is a key issue and negatively impacts the country-of-origin image. Many consumers, for example, still perceive China as a copyright pirate-infested zone and a supplier of poor quality, even tainted, goods.

Meanwhile the country-of-origin image can be viewed using six dimensions: quality (reliability), innovativeness, aesthetics, prestige, price/value, and social responsibility. While few developed countries score favourably on all dimensions, what differentiates developed countries from emerging markets is that the latter tend to rate low on all aspects except price.

One of the biggest challenges many emerging markets face as they globalise is the perception that their brands are inferior.

Overcoming negative country-of-origin associations

Brands from emerging markets need to think about what is credible and what resonates with western consumers. Nation branding is also a means of countering country-of-origin concerns. For example, ‘Malaysia Truly Asia’ and ‘Incredible India’ are familiar brand slogans. When South Korea climbed out of its emerging nation status, it launched the Presidential Council on nation Branding’ and took the opportunity to showcase the country’s economic development at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. it continues to spend billions and uses events to enhance the country’s national image and brand.

We propose seven strategies to overcome negative country-of-origin associations:

![]() 1. Disguise the origin in choosing the brand name

1. Disguise the origin in choosing the brand name

The evidence from research is clear: using a foreign brand name is effective in overcoming bias against the country-of-origin of emerging markets. Nothing in the names Lenovo or ZTE suggests they come from China. Choose a brand name that triggers favourable cultural stereotypes and influences product perceptions and attitudes. Highlight that key components come from developed markets.

![]() 2. Confront negative associations

2. Confront negative associations

Where there is a lack of information, persistent media stereotypes, or an overexposure of negative media events and national figures, acknowledge existing perceptions and then challenge them.

![]() 3. Focus on favourable ‘nuggets’

3. Focus on favourable ‘nuggets’

Consider whether there have been credible items within the broader product category where your country-of-origin has an advantage. As Zhou (Joe) Wang of China’s Jahwa said, western perceptions of China revolve around words such as “old, low quality, low trustworthiness, and unsafe”. In contrast, Shanghai is associated with “cosmopolitan, dynamic, fashionable, fresh looking and energetic”. This saw Jahwa revive one of its famous nostalgic brands, renaming it ‘Shanghai Vive’ to capture the feeling of old Shanghai.

![]() 4. Offer post-sales service

4. Offer post-sales service

Low-quality manufacturing is the biggest hurdle for emerging market brands, and extra guarantees and other types of warranties and services over and above industry norms help to reduce purchase risk. Euro NCAP, the European safety agency recently awarded China’s car manufacturers Geely and SAIC four marks out of five for quality.

![]() 5. Emphasise aesthetics and invest in design

5. Emphasise aesthetics and invest in design

Even the most naïve consumer can readily observe and experience aesthetic qualities. Brilliance China automotive hired Dimitri Vicedomini from the famous Italian design house Pininfarina, which designs for Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Maserati and Peugeot (coincidentally acquired by India’s Mahindra in December 2015).

![]() 6. Utilise reverse manufacturing

6. Utilise reverse manufacturing

China garments is a state-controlled company that went on to create a luxury menswear brand using Chinese design with European manufacturing quality. Its CEO, Zhan Yingjie, said, “We want to turn around the old thinking that we can only do processing. China has the ability to create its own luxury brand…China isn’t just a global manufacturing centre and Italy a global design centre. These roles can be mixed.”

![]() 7. Invest heavily in marketing

7. Invest heavily in marketing

This helps to raise brand awareness and to create positive brand associations. For example, next to innovation, the second key component of Samsung’s rise to global esteem was prolonged heavy spending on advertising and other marketing efforts. Thai Beverage, one of the leading beverage producers in the world, invested heavily in sports sponsorship (as did Emirates) including football teams (real Madrid and Barcelona).

Carpe diem

in contrast to a quasi-monopoly brand that consumers buy because they lack any other option, the principles of developing a strong national brand do not differ from those followed by any other company. The national champion must seize the moment, define its target segment, develop a brand promise or position, and determine a marketing mix to fulfil the brand promise.

Brands are always a work in progress. Although hurdles remain for national champions from emerging countries before they can break free and reach their full potential, this is nothing new in the life of a global brand. Both the U.S. and Japan faced similar issues in their pre-global powerhouse days. But rather than balk at the prospect of this latest leap forward, firms need to improve their transparency, enhance the profitability and integrity of financial statements, move from imitation to innovation, accept management diversity, and strive for a global mindset. The evolving global market place is definitely no country for old men (or women).

The material for this article is derived from the authors’ published book Brand Breakout: How Emerging Market Brands Will Go Global.