Educators have had to answer criticism that business schools have failed to keep their ‘eye on the ball’, that is, the very core, purpose and value of management education. In pursuing academic scientific rigour, critics claim business schools have swung too far down the path of rigour at the expense of relevance. More deeply offending for those who strive for relevance and value above all, is the assertion that schools are failing to adequately prepare students to deal with real-world management problems. In essence, there is a disconnect between business schools and the perceptions of the wider management audience they serve.

It is against this backdrop that one might ask what the future of management education might look like. Bleak as the situation might seem, heightened awareness of the dangers on the horizon should prompt action and lead to innovations in business school models. But on the other hand, given the inertia that has been characterising business schools, management education might also find itself sinking in quicksand.

To anticipate likely shifts in the management education landscape, my team and I surveyed 39 leaders in management education to establish possible future scenarios for the field. We then sought their insights on what they perceive to be the most likely, best-case, and worst-case scenarios for the next decade. While not forecasts in the strict sense, the scenarios are better considered as a mapping of possible long-term outcomes based on a range of trends, events and pathways. Leaders also volunteered their perceptions of the challenges and likely impact on the evolution of the field.

The time is right for change. However whether management education as a fi eld, and its leaders as its strategists, have the will and the capacity to respond to the challenges that confront it remains to be seen.

Critics claim that schools are failing to adequately prepare students to deal with real-world management problems.

Heads in the sand versus re-aligning the compass for change

Consistent themes emerged. Viewed together, they represent a ‘compass for change’ and a response to various external and internal challenges faced by individual business schools. The first challenge mentioned was the culture of business schools. Characterised by inertia and a certain resistance to change, their currently problematic nature is due largely to conservatism, complacency and a ‘head-in-the-sand’ attitude towards the challenges that confront management education. This attitude, which demonstrates an entrenchment in the existing ways of doing things, is a cognitive issue. Business school deans who are comfortable in their roles would favour in their minds a ‘dominant recipe’ for approaching management education. This would in turn lead to ‘blind spots’ when it comes to recognising and seizing innovative opportunities to bring about positive change.

The actual purpose of management education is another matter, and the debate as to whether or not it should enhance managerial capabilities or generate intellectual capital is intense. Pedagogy used and curricula content were other factors identified as being in need of revitalisation. Deeper still were the challenges of the faculty structure itself, and the funding of business schools.

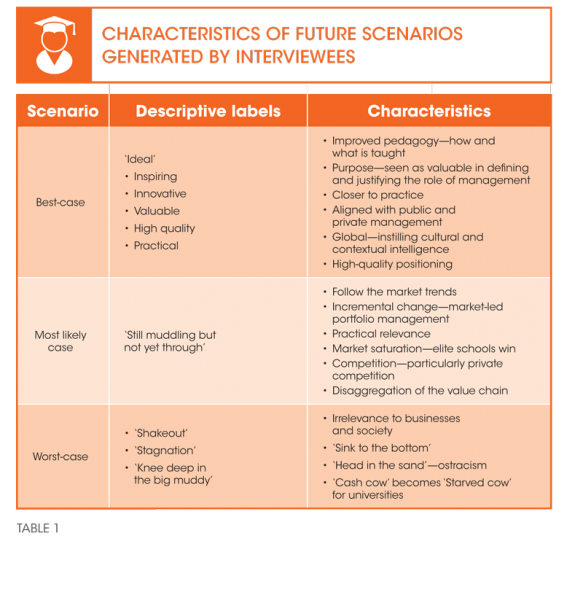

Leaders acknowledged the themes during the process of developing the three scenarios, which the team and I have described as ‘muddling through’ (for most likely), ‘shakeout’ or ‘stagnation’ (for worst-case) and an ‘ideal’ scenario (for best-case), which are presented in Table 1. The modal response for the most likely scenario was one where intense competition pushes schools to specialise and better differentiate their offerings, as they attempt to strengthen their position in the market. The best-case scenario was one where schools move closer to globalisation and practice in an attempt to regain relevance and legitimacy, with the worst-case scenario described as a situation where management education as a whole fails to respond to the criticisms and challenges, leading the field down the path of greater and greater irrelevance.

Best-case scenario: ‘Ideal’

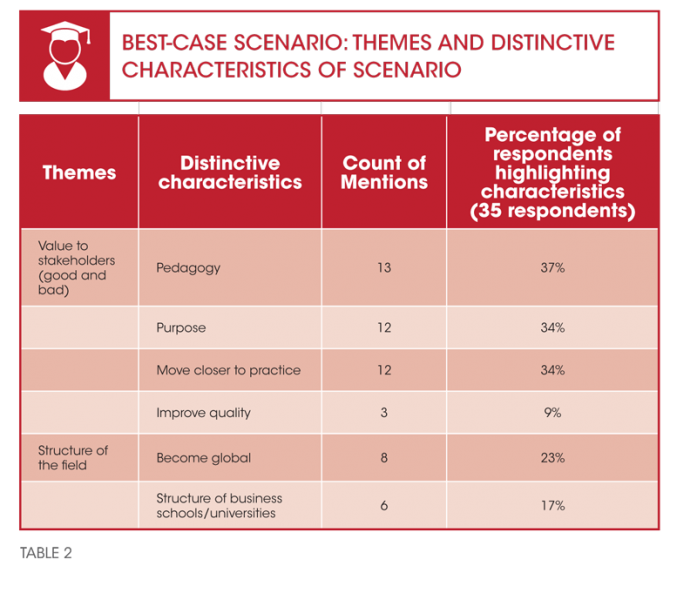

The research revealed significant differences from the status quo when it came to best-case scenarios. Scenarios articulated are aspirational, and often quite removed from the way that business schools and their offerings are currently arranged. Almost three-quarters of responses stressed the creation of more value for stakeholders, while the remainder covered the structure of the management education field itself. Table 2 provides the characteristics identified during the interviews with educators.

Key findings related to the nature of pedagogy in business schools, the refocusing of management education and bringing schools of business closer to management practice. Of interest was the observation that a small number of responses viewed the quality of management education in the best-case scenario as being significantly higher than current levels.

Interestingly, the best-case scenario also incorporates pedagogical improvements that are viewed as providing value to stakeholders, inspiring better managers and being of greater relevance. The comments reflect the debate about curricula overemphasis on business and analytical skills, and under-emphasis on skills such as leadership, global awareness, problem framing, problem solving and integrative thinking. Or, put another way, the balance between domain knowledge and the skills of problem solving, criticism and synthesis that is necessary to operate in an ambiguous and multi-disciplinary management environment. More pragmatic interviewees asked whether we, as educators, really understand our ‘end product’ and whether we feel confident that we are producing good managers; and called for closer alignment with practice. Once business school research is perceived as more relevant to the business world, they reason, the more respect for the business school that would be engendered, and the greater likelihood of sponsorship for school events and projects.

The structure of the sector itself piqued the attention of just over 26 percent of responses, drawing attention to two aspects of management education: the organisation of business schools (often, but not always, as part of a university system) and the capabilities of schools. Some of the best schools are perceived as part of a university system, where, through reputational capital, they obtain greater autonomy and thus have greater agility in responding to market conditions. It allows them to innovate—rather than, for example, focus on the preparation of students to meet accreditation requirements. Yet there are also ‘standalone’ business schools of high quality, such as INSEAD, IMD and London Business School, which often take risks, innovate and more flexibly address opportunities.

There can be few other disciplines where there is such a marketplace emphasis on getting your students into good jobs. Good business schools excite the passion and acumen of outstanding students, which in turn enhances reputation, as well as attracts premium faculty.

The best-case scenario also accommodated the need to become more global, a state that goes hand in hand with the rise of players in Asia and Latin America, providing strong diversity and the creation of a range of different models of management education. In 2015, it is understood that the great global corporations cannot just go to the very few business schools that are global. Global is more than geography; it has to do with the mentality of people becoming globally aware, that is, culturally and contextually intelligent. Business schools need to produce ‘go anywhere, global graduates’. The development of global capability married with local knowledge is an urgent need for management education in the current era.

Management educators interviewed also felt it was time for proper reflection on the purpose of business schools in particular, and the Holy Grail of management education in general.

Most-likely scenario: ‘Muddling through’

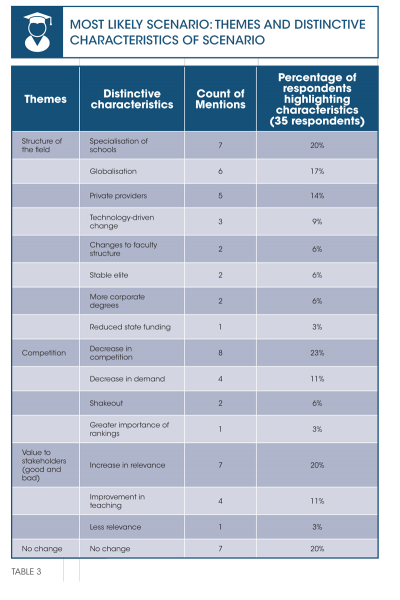

Given the previous comments, it is hardly surprising that in the most likely scenarios, interviewees placed far greater emphasis on the structure of the field than in either the best- or worst-case situations. Competitive pressure is seen as playing a strong role in how respondents perceived the future unfolding, while value to stakeholders and no change respectively received less attention.

The distinctive characteristics differentiating the most likely scenario from the status quo are given in Table 3, and reflect the four basic themes mentioned earlier.

More schools are expected to differentiate themselves by moving in a range of strategic directions such as internationalisation strategies, more specialised (niche) strategies, and adoption of lower-cost provision by private providers as they reinforce their market entry strategies. As one interviewee noted: “I see in the developed world a stronger specialisation. We will have a stronger push for business schools to be more specifi c on their positioning. I think the growth of portfolio-type business schools will increase this pressure very heavily. So competition will push things, at least in the most developed countries in which our selling market is more mature…towards a kind of specialisation.”

One of the key elements here is the decline in government-level funding for management education and the ensuing struggle for financial resources. It impacts not just public universities. Major private universities too are vulnerable, especially if government funds and grants are withdrawn—perhaps even half the university would go, says one educator, although the business school could probably still operate.

Declining funding might see governments more likely to meddle more than they currently do, but it is also seen as leading to disaggregation in the value chain and a strong review of such elements as technology-enhanced learning. One likely scenario is the fragmentation of education outside of the university, where diversity is encouraged, with some people doing self-study and consuming shorter programmes, including the massive open online courses (MOOCs). Others, including MOOCs, may also provide and offer ways of flexible degree certification.

Worst-case scenario: ‘Shakeout’ or ‘stagnation’

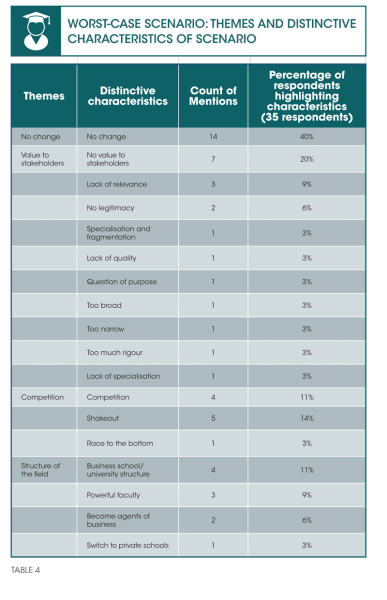

Four main themes became apparent: no change; where management education fails to provide value for its stakeholders; where intense competition damages the field; and where the field’s structural qualities undermine its effectiveness. A combination of the above themes too emerged.

Just over a quarter (26 percent) of comments were related to the problem of no change and over one-third (36 percent) were concerned with not providing value to stakeholders in management education. There was broad consensus (40 percent) that no change was the worst-case scenario, a fifth (19 percent) discussed concerns about the damaging effect of competition within the sector and the same proportion of responses (19 percent) indicated that structural issues in the sector would underpin the worst possible case for management education. To deepen our understanding of areas that trouble leaders, the four themes are explored in further detail in Table 4.

Forty percent of educators considered the worst-case scenario as involving complacency, no change, and a ‘head-in-the-sand’ position. However, maintaining the status quo is inappropriate for business school programmes. Change is essential. As one interviewee noted, some business schools have been churning out programmes that have not been materially revised, updated or redesigned in 20 years.

However concern that the value proposition is not being articulated well for stakeholders is a more nuanced and multifaceted argument than the argument that there would simply be ‘no change’ in the worst-case scenario: 43 percent thought the worst-case scenario would be one where the value of management education would be an issue. The lack of value leads ultimately to a situation where stakeholders choose to ignore or substitute the content of management education. Without a credible value proposition, business schools become somewhat redundant in both business and academia. The absolute worst, said one interviewee is that “we don’t really need an MBA anymore, that it’s not something that is relevant and not worth paying for”.

Competition in the worst-case context takes the form of two types of threats. The fi rst arises from strategies private providers are likely to use and how these strategies would affect the competitive dynamics in the industry. The second focuses on the competition for scarce resources that occurs particularly in the realm of universities. This predominantly concerns competition for students and faculty, as more global players develop and as schools in some countries make the transition away from a state-funded model. As a result, financial sustainability and ultimately survival becomes an issue, leading to a shakeout in the field.

In such worst-case scenarios, a sense of despondence is palpable in management education and it becomes increasingly irrelevant to stakeholders under these circumstances.

The shifting landscape could have heralded innovation, but it has not. The lack of innovation in turn reflects resource constraints as management education evolves in an easterly and southerly direction. For example, Asian management education is diverse and heterogeneous, and has its own context and priorities. While India faces a shortage of faculty, China faces constraints in academic autonomy.

There is no single management model in Asia, as the experiences of India and Japan show. India, for example, has produced many key educators and thought leaders such as C.K. Prahalad (Michigan), Vijay Govindarajan (Tuck), Nitin Nohria (Harvard), Sumantra Ghoshal (LBS), Lord Desai (LSE), Ram Charan (author and consultant) and Jagdish Sheth (Emory). Yet despite producing some of the most influential of educators, the Indian system has its drawbacks. Only four institutions are accredited by key international agencies (e.g. AACSB/ EQUIS). It is low on research output: there is no Indian School in the UT Dallas ratings and little international/ global impact/reputation, as shown from the Financial Times and Economist rankings. There are also many suppliers of uneven quality of instruction outside of the elites (such as the IIMs, and IITs and the like).

Meanwhile although the Japanese management education environment has many business-related departments at undergraduate level, there are relatively few graduate business schools (other Asian powers have expanded faster). Nevertheless, the science-based engineering-oriented culture has produced many national and international champions that include Fujitsu, Canon, Toyota, Honda and Sony, as well as resulted in a respected international business profile.

In 2003, a change in the Japanese regulatory environment established ‘professional graduate schools’. MBAs are mostly studied on a part-time/evening basis and have a relatively lighter workload if compared to Western schools. In common with India, there are quality standards and accreditation issues: few Japanese schools are accredited by key international agencies and the system has issues of economic growth, globalisation, the internationalisation of human resources and the strategic use of human capital. The question for Japan is whether it can influence the growth of management education and fulfil its considerable promise in this field.

In the Asian Management Model, there is ‘no meaning without context’. Asian management education is diverse, and there is no single, dominant model. There are different cultural and contextual priorities in China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam. Each country is unique. The question for the Asian management countries is how they can help each other and forge greater ties in developing Asian management education.

Here in Singapore, business schools benefit from strong government backing and healthy public funding of higher education. However there is significant government oversight and the larger goals of the nation, such as the manpower needs of the economy, impose performance expectations on business schools and have an influence on their strategic direction. In contrast, business schools in the U.K. face the challenge of drastic cuts in funding and a limit on how much tuition fees can be raised to increase revenues.

And then there’s the competition

In both best- and worst-case scenarios, competition was particularly mentioned as a key driver of change. The pressure is intense and is likely to impact management education in many ways, including the shakeout of weaker schools due to underinvestment in teaching and poor pedagogy. Business education can be done very cheaply and can also appear credible with the inclusion of a few teachers from industry. However their inclusion doesn’t mean that they are necessarily good.

Increased competition may well intensify market segmentation and drive schools to search for distinctive differentiation strategies. However it also has a negative side, including use of ‘creative approaches’ to scaling new heights in the reputational rankings and doubtful strategic alliances. Proprietary (for-profit) institutions are also going to be stronger, and able to deliver better content more effectively, using a myriad of channels.

The value proposition of the research-driven business school is also destined to come under increasing scrutiny, forcing university-based business schools to justify their positioning and clearly rationalise what they do. Given the competition from low-cost providers, this will likely lead to a focus on issues of relevance (in research and teaching) and the need to provide value in a sustainable way.

But other educators have flagged ‘no change’ as likely, that is ‘business as usual with some frills’ or ‘business as usual and muddling through’.

The most likely scenario is probably one where competition is intense, with the biggest threat from for-profit providers with the capabilities to offer the same product or even a higher quality one at a lower cost, as well as an increasing number of international players.

The road to ‘muddling through’

There are clearly prescriptive implications in our findings if schools are to avoid being driven out of the market and falling under the wheel of for-profit competition. They will need to negotiate around the constraints mentioned earlier and hurdle such barriers by creating innovative solutions.

Firstly, the fact that the worst-case scenario is described as one where there is a lack of change suggests more flexible models of education, with the pure brick-and-mortar approach superseded by new learning technologies that offer greater flexibility in the delivery of programmes, accommodate distance learning, and are less reliant on case studies as the value of experiential, action-based learning is increasingly acknowledged. MOOCs can, for example, offer flexibility in the pace and mode of learning and may bring cost efficiencies, and schools ignoring the potential of MOOC platforms do so at the risk of their own demise.

Secondly, efforts must be made towards a closer alignment with practice as research becomes more applied. There is also a great need to develop individuals holistically and to change the language used in classrooms from shareholder- to stakeholder-speak. Business schools can no longer afford to ignore larger societal issues. Curricula content is another area mentioned as having failed to keep up with its environment and has therefore lost its currency.

Thirdly, the ecosystem cannot support a growing number of business schools all competing for the same limited pool of faculty, limited numbers of pages in journals and a limited pool of MBA candidates. The biggest threat is likely to come from for-profit providers with the capabilities to offer the same product or even a higher quality one at a lower cost, as well as increasing numbers of international players.

Fourthly, differentiation is an imperative for survival but requires a keen understanding of the competitive landscape and points of difference that will be valued by the market. This could mean re-engineering the mix of programmes and the introduction of short-term courses, mergers and partnerships between universities, business schools and others.

Lastly, the university system itself needs to change. Governance policies, internal bureaucracies, tenure, autonomy or the lack of it, all limit the agility needed to respond to challenges. A combination of balance of power favouring faculty and incentives skewed towards research publication creates a fairly imposing roadblock to change. In the case of tenure, the relatively short-term nature of the tenure of deans—around four years—also works against the introduction of change, and lessens courageous and authentic leadership, especially when drastic or unpopular change is required.

Ultimately, there is a need for the field to secure its own future by going back to the fundamental purpose of management education—that is, to produce effective business leaders and to conduct research that has impact on the practice of management. Without the presaging of a movement towards real-world management and the sharpening of their positioning, schools risk becoming drowned out in the cacophony of competitive marketing, or simply sinking knee-deep in the big muddy.

Management education is most definitely at a crossroads, and the path forward is obscure. While it is tempting to stand still, we, as custodians of the field, must reflect on the changes we need to enact, so that the legitimacy and the future of management education is ensured.

Without the presaging of a movement towards real-world management and the sharpening of their positioning, schools risk becoming drowned out in the cacophony of competitive marketing, or simply sinking knee-deep in the muddy.