Is a distinctive African management education model possible, achievable, or even advisable?

Little has been written about management education in Africa and yet there exists a huge demand for managerial skills in order to leverage the potential of Africa’s economic growth. For the most part, the existing management education programmes reflect the evolution of schools of thought from a variety of countries, mostly from Europe and the United States. Limited attempts have been made to create uniquely African management education programmes, with some questioning whether an African model is even feasible or desirable. This is just one of the issues explored in a recent study undertaken by the author1 and outlined in this article.

The role of and challenges facing educational development in Africa at every level can only be understood in terms of the varied history, contexts, cultures and issues that exist in its 54 very different countries. It is a continent with a population of more than one billion, with 3,000 distinct ethnic groups speaking 2,000 languages, each of which has its own political, economic, and sociocultural structure inherited from both their unique traditions as well as their respective colonial legacies.

Some of the world’s fastest growing economies–Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast and Mozambique–are African. And so are some of the world’s poorest. Although Equatorial Guinea has a 94 percent literacy rate (the global average is 84 percent), in South Sudan it is 24 percent. Africa remains the world’s least developed continent with the greatest proportion of economic growth concentrated in just 10 countries, including Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa. About 80 percent of African states can probably be best described as ‘developing’.

While there exist acute shortcomings of infrastructure across the continent, infrastructural development is not consistently poor across Africa. In cities that have attracted foreign direct investment, there is now greater ease of doing business. Chinese interests, for example, are building the Nairobi airport and roads in Lagos. Despite the challenges, Africa is now considered an attractive investment destination, described by The Economist as the world’s ‘hottest frontier’.2

Private sector investment in Africa is generally the result of foreign direct investment. Despite this, some African countries have tried to adapt and formulate a range of strategies for economic growth management, and pursue international and interregional trading opportunities arising from globalisation.

Funding is challenging for many African nations, while an additional constraint is the relative poverty of 70 to 80 percent of African countries. This means that new African management education paradigms must be low-cost, efficient and capable of leveraging mobile technology to allow such education to be available in both urban and rural areas. The impact of corporate involvement in the education process—a factor that is often taken for granted in developed countries when designing programmes and setting curricula, is also relatively unknown.

With these concerns in mind, the research undertaken included a range of in-depth, two-hour, open-ended, face-to-face interviews with leading management educators and stakeholders. In addition, perceptions of a representative subset of 20 interviews with key players provided a retrospective view of the evolutionary pathways of management education in Africa over the last two decades. The interviews themselves reflect the wide range of environmental, cultural, contextual and regional characteristics exclusive to the African scene that have clearly shaped African approaches to management education.

Africa’s management education landscape

African countries and their business schools are developing at different rates of growth. They exist within an environment that can be characterised as volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous, with turbulence and change constantly present, as well as one where there is an urgent need to generate many new employment opportunities.

In some African nations, there are few, if any, business schools. The Association of African Business Schools (AABS) and others suggest that Africa is clustered into (at least) five sub-regions: North Africa, Southern Africa, West Africa, Central Africa and East Africa. There is huge variation in the ways of doing business, both within regions, and within individual countries, and a range of different forms of business schools across Africa is thus expected. Additionally, the schools should not necessarily be thought of as carbon copies of models from distinctly different contexts such as the United States or Europe. One size does not fit all.

Many universities are vocationally oriented while others seek to model the West. The diverse set of business schools that exists has attempted to achieve a balance between mimicking western models, and country and regional factors of differentiation. Only a relatively few elite schools in Africa have an orientation and resource profile that matches, or even approaches, the best American and international business schools—although that may not necessarily be an appropriate benchmark for an African identity and approach in the field of management education.

Where African schools have an international mindset that involves a strategic intent to achieve international accreditation and favourable media rankings, they stand in almost complete strategic isolation from the typical vocationally-oriented African business schools.

African management educators have generally emphasized management practice over theory. They have tended to deemphasize strong analytical rigour and the pursuit of scientific management research, which is perceived as offering little immediate practical relevance for a managerial audience.

They also prefer a closer relationship with business and practice, favouring a faculty role as teacher-first, and offering a blend of practical experience and knowledge to students. Teaching methods vary sharply, as do the minimum educational requirements in regions where literacy and schooling levels are disparate.

COUNTRIES LEADING IN MANAGEMENT EDUCATION

Countries and regions that were mentioned by respondents as being at the forefront of management education in Africa over the last two decades were: South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria and Egypt.

Business schools in South Africa, for example, were perceived as ‘top tier’ because of their similarities to western business schools in terms of pedagogy and programmes offered. Second tier schools aspired to become first tier. The third tier comprised schools that operated within universities and were very traditional in their approach and offered vocationally-oriented courses. Interestingly, Kenya was perceived by two-thirds of respondents as the country at the forefront of management education in Africa.

Slightly more than half of respondents placed Nigeria as the third leading country for management education. Egypt, straddling the Middle East and European regions, was placed closely alongside Nigeria, perhaps due to its close proximity to Europe or its contribution to the development of management education in the Middle East. All four countries mentioned shared strong education systems.

Current issues

Although there are approximately 100 management and business schools throughout Africa, only 10 or so are of international standard. Important issues cited by respondents included the need to develop a management education ecosystem, to design new business models for African management education that would offer strong practical and entrepreneurial training, and to address a skills shortage among the one million lower- or middle-level managers.

Large-scale management education and development is needed to provide managers with key skills such as drive, ethics/integrity and practical experience. Given that the most significant job growth tends to result from entrepreneurial activity, there is also an urgent need for training entrepreneurs and small and medium enterprises.

The issues raised in the interviews could be classified as either more broadly contextual, or as issues specific to management education:

CONTEXTUAL ISSUES

![]()

Dominant role of governments

This relates to heavy regulation, including government involvement in the admissions criteria and course delivery, which is seen as intrusive and burdensome. Generally speaking, it involves the relative dominance of non-academic stakeholders.

![]()

Competency levels of students

It was noted that, often as a legacy of colonial rule, different educational systems existed within different countries. This inconsistency was also reflected in the levels of functional literacy existing within the continent. In many cases, there was a need to get students ‘up to speed’.

![]()

Diversity

Africa’s diverse environment calls for diversity in approach. The colonial legacy, apartheid, and issues of gender, faith, poverty, etc., have made developing management education for those other than affluent, white males a challenge.

![]()

Inadequate infrastructure

Much of Africa continues to face the challenges of unreliable electricity, inadequate buildings, poor roads and limited Internet accessibility, despite pockets of development in several major cities.

ISSUES WITHIN MANAGEMENT EDUCATION

![]()

Lack of quality in African business schools

Africa faces a scarcity of business schools, with standards in some existing institutions not always inspiring confidence. This tends to tie in with difficulties related to faculty recruitment. Pedagogy and curriculum may emphasise rote learning than active student engagement, and vocational needs may be given more focus than problem-solving, leadership and other higher-order people skills, and project-based, practical experience.

![]()

Faculty issues

Industry or practical experience plays a dominant role in the selection criteria used by African business schools. This is in contrast to research ability, which is rated highly in North American and European business schools. Attracting faculty (and international students) is difficult.

![]()

Changing competitive landscape

Competition is in the form of foreign entrants, and partnerships between local and foreign schools. In order to compete effectively, there is also further pressure to create ‘global’ graduates with the knowledge and skills to operate both inside and outside Africa.

Respondents stressed a more practical focus on ‘getting things to work’, compared with esoteric issues such as the meaning and purpose of management education. The impediments to achieving high quality in business schools, and concerns about how management education could be made more relevant and responsive to the business world, were also mentioned frequently.

Many business schools are part of larger state universities that do not necessarily understand the business of management education and are somewhat divorced from the world of business. This raises some fundamental questions: For whom is management education intended, and what is the purpose of business schools in Africa? The relative dominance of non-academic stakeholders may also mask a more serious and enduring feature of the political landscape of the continent–political instability and a lack of co-operation among countries.

Events in management education

As an increasing number of world-class institutions are attracted to Africa, African business schools have had to raise their game. Over the last 20 years, a significant number of important events in management education have taken place. Four main events, or themes, were identified by the deans and stakeholders. These were:

![]()

Partnerships

The establishment of AABS, which provides a platform to unite African business schools, was seen as very important. Partnerships and relationships have been formed between business schools based within the African continent, as well as business schools outside the continent, including Harvard, IESE Business School, Insead and London Business School. Such partnerships were viewed as highly valuable in terms of building capacity to meet the strong demand for trained managers, and for sharing information and knowledge about teaching pedagogy and research.

![]()

African growth

Another event, or theme, that was considered critical was the widespread recognition of the need to deal with the outside world. This has encouraged African nations to rethink the way they do business with globalisation viewed as an enabler in securing better relationships with international businesses and organisations. However, economic growth and wealth inequality are also seen as raising the possibility of unequal access to management education, and confining the benefits of management education to select groups in African society. Moreover some considered globalisation to be a double-edged sword in that it brought external competitive pressures on rankings, accreditation and the need to form international networks.

![]()

Technology

Not surprisingly, technology was seen to have had a huge impact, especially mobile technology and the Internet. Greater access to the Internet, in some but not all countries, has also made online education possible, although growth has been at a moderate pace.

![]()

Political change

Politics were also considered to have had a major impact on management education. Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 and the end of the apartheid era in 1994 were cited as important political events that opened up new possibilities in Africa and greater connectedness among business schools, greater interaction between schools and increased exposure to international practices. This was seen by some as opening up opportunities for academics to go overseas and see and experience tertiary education at other institutions. Another suggested that an unstable and uncertain environment has become the catalyst for establishing new views and new identities, particularly among the young.

Towards a proposed African-oriented business school curriculum

Those interviewed were asked whether it was realistic to think in terms of an African model for management education. And, if not, what local adaptations might be appropriate?

Although some respondents indicated that, if certain adaptations were made, there could be some form of an African model for management education, slightly less than half of respondents said that such a model was not realistic. Of interest was the comment by one respondent who said that the most important thing in launching an African model was, “not to isolate Africa even more by having our own model”. Only a very small minority of the interview panel favoured a single African management education model.

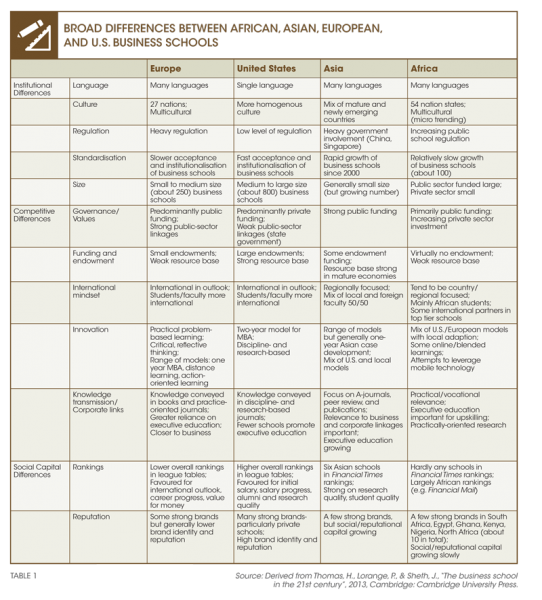

Some respondents also expressed the possible inappropriateness of the western business school model in the African cultural context–while there is an emphasis on individualism in the western context, African culture strongly promulgates ‘Ubuntu’ or communitarian ethos and collective unity. Nevertheless, foreign management education schools and academic partnerships with the world’s leading universities and business schools continue to be significantly present. The broad differences between European, U.S., Asian and African business schools are outlined in Table 1.

UNIVERSAL OR SITUATIONAL?

Respondents debated whether or not the theory and practice of management itself is universal. Two-thirds of respondents argued that it is a global model that transcends continents, including Africa. A smaller group of respondents considered management to be local and situational, although the many differences among different regions and groups of people might rule out the possibility of a coherent African model.

Respondents also considered the role that other models of management education play in enabling or constraining the development of an African model. For some respondents, the western model embraces institutional, academic and business power. One respondent questioned the relevance of Harvard business case studies that talk about innovation. Another raised the issue of the relevance of the short massive open online courses (MOOCs) presented by the world’s leading universities, “while we don’t have [adequate] electricity in Kenya”. Some respondents felt that, in the face of a western-dominated sector, some variety of an African model should be seen as aspirational, “Maybe not building a model but setting up our own set of criteria as a beginning? So that we don’t compete with the rest of the world initially but we compete with ourselves.”

Ultimately, any discussion of an African model requires a clear and thoughtful definition of that proposition. As one respondent noted, “The importance of understanding Africa’s needs is there, but we’re still on a journey of understanding what these true needs are.”

What would an African management model look like?

Although there is broad agreement that better managers and management are essential for Africa, the precise form that management education should take—a model that would impart knowledge and skills relevant to Africa and tailored to the needs of Africa—is unresolved.

While one respondent spoke of an African business school model as one that focused on social innovation, business model innovation, inclusiveness, and entrepreneurship, others were still considering what should be included.

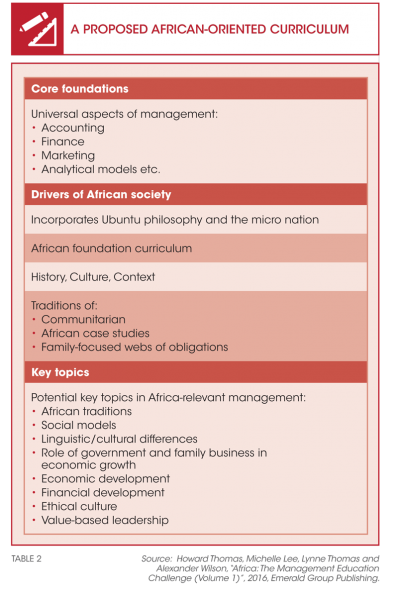

A holistic African-oriented business school curriculum design is proposed in Table 2. This design suggests that there could be a range of African business school models rather than a single African paradigm.

Conclusions

African business schools face several fundamental challenges, perhaps even before a specific African model can be considered. As noted by Abdulai3 and some of the African deans interviewed, such challenges include the need to identify high-quality faculty and overcome faculty shortages, as well as address the potential influences of globalisation and innovation on curricula. Account must also be taken of the impact of new technologies on management education in areas such as MOOCs and distance/blended learning. Another challenge is that management education may not be affordable for all due to cost and capacity constraints.

Funding permeates the management education challenge. Not only is there a lack of resources for sustainable quality management education and inadequate funding for areas such as management research, there is also an imbalance between public and private ownership in the management education sector.

Meanwhile, in considering a specific African model, several African academics including Abdulai, De Jongh, Naudé and Nkomo have argued for Ubuntu—‘I am, because we are’—as a guiding principle and moral philosophy. Ubuntu is able to offer a different framework, although further research is needed to establish what is required by, and of, managers throughout Africa.

And as the business schools in Africa seek to grow, they will need to strive for a balance between international, regional and local demands. More importantly, African business and the management education communities need to build an even, fair and strong relationship both among themselves and with the government and the wider society that, in turn, is able to reflect the fulfilment of mutual expectations about the potential value and impact of management education. It is a work in progress.

Howard Thomas

is the Lee Kong Chian School of Business Distinguished Term Professor of Strategic Management and Management Education; MasterCard Chair of Social and Financial Inclusion; and Director, Academic Strategy and Management Education Unit at Singapore Management University

The material in this article is derived from the author’s recently published book: “Africa: The Management Education Challenge (Volume 1)”, co-authored with Michelle Lee, Lynne Thomas and Alexander Wilson.