Iuiga, a lifestyle retailer, has a curated range of high quality products at transparent, affordable prices, effectively leveraging the original design manufacturers’ model and an online retail platform.

Iuiga is a Singapore-based e-commerce start-up that has eschewed the conventional e-retailing model by acquiring complete control over its value chain—from ownership of its retailed items to marketing, storage, logistics and distribution. Positioned as a lifestyle brand, the start-up targets quality-conscious customers and presents a curated range of high quality products at affordable prices. Iuiga launched its mobile app in May 2017, followed by its website two months later.

In 2015, Zang Hao, the CEO and founder of Iuiga, and his three partners, decided to adopt the original design manufacturers (ODM) business model for sourcing products. Iuiga contracted the manufacturers of big global brands known for their superior quality to manufacture the same products for them. The products, bereft of the premium brand tags that commanded hefty mark-ups, were then retailed directly by Iuiga under its own brand name at much lower and transparent prices on its website and mobile app.

Iuiga recorded a good start with monthly sales growing from 600 units in the second month to 3,000 units by the eighth month. The upward trend was short-lived, however, and by the ninth month, sales growth began to plateau. The e-commerce brand was at a crossroads. How could it sustain growth? Was it simply a matter of committing more resources and effort behind its online platform? Or did it need to adopt a radical strategy and go physical, which was the antithesis of its core business model?

The management team debated whether the company should enter into omni-channel retailing, and considered setting up pop-up stores. At a time when physical retailing was predicted to be on its last legs, and online retailing was being hailed as the rising star, would going physical be the right thing for Iuiga?

|

SINGAPORE’S E-COMMERCE MARKET The e-commerce market in Southeast Asia was expanding fast, forecasted to grow at a CAGR of 14 percent between 2017 and 2024.1 In the region, Singapore promised to be a leading market, given its high Internet penetration, urbanized population, wealthy consumers, and a mature transport and delivery network. While the country’s online share of total retail sales was small at 5.4 percent, it was the highest in Southeast Asia, and poised to grow rapidly.2 The largest consumer segment to shop online was those between 25 and 34 years old, followed by those aged 35 to 44 years old.3 In 2017, the number of active Internet users in the country stood at 4.47 million.4 Over 90 percent of the population had access to the Internet and used it every day, spending an average of seven hours and nine minutes online per day, with 26 percent shopping online at least once a week, and 58 percent at least once a month.5,6 |

A recipe for success for Asia's F&B franchising Iuiga’s business model

The ODM model is based on manufacturers undertaking R&D and product development according to a buying firm’s specifications, as well as manufacturing the final product. The buying firm selects the design and quality and places an order with the ODM. The ODM delivers the final product, which is then branded by the buying firm as its own and sold in the consumer market according to its pricing strategy.

The ODM model offers a win-win situation to both parties. With ODMs providing design and product development services at no extra cost to factory production, buying firms can focus all their resources on brand-building, marketing and distribution. Manufacturers, on the other hand, gain by having the copyrights for product and design, enabling them to sell to multiple clients and accrue operational efficiency, optimal capacity utilization and lower costs of production. However, an ODM, unlike an Own Brand Manufacturer (OBM), does not own the brand under which the products are sold in the consumer market.

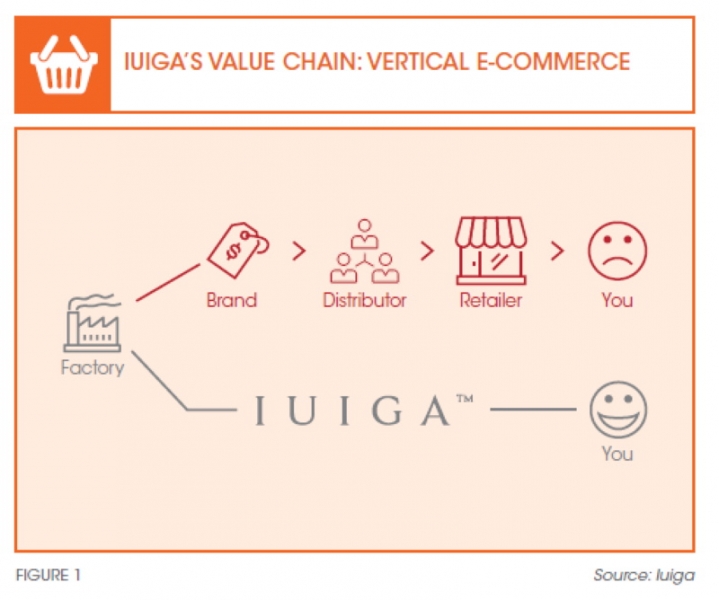

Adopting the ODM model, launching its own brand and integrating the supply chain allowed Iuiga to have control over costs incurred, pricing strategy and the value created (refer to Figure 1). Chinese ODMs were the logical choice for Iuiga on two counts: China offered high levels of innovation at the lowest costs of production worldwide, and the company founders had extensive knowledge, experience and a network in the local Chinese market.

However, the ODM model approach was uncharted territory for Hao and his partners, and resulted in the team spending close to two years in China to identify, select and negotiate with the manufacturers and get them on board. The entire process was painstakingly slow, riddled with numerous issues and rejections, and demanded considerable investment of resources. However, insights into China’s macroeconomic environment and the challenges faced by the manufacturing industry in the country helped Iuiga present an opportunity to the ODMs to expand into new markets like Southeast Asia, hitherto inaccessible to them, and to curtail their over-dependence on certain global brands. By 2018, persistent effort and adaptability gradually led the company to win favourable contracts with close to 200 ODMs, who produced for global brands such as Muji, Samsonite, Sephora, Under Armour, L’Oréal, and Crate & Barrel.

CHOOSING A CATEGORY

After careful consideration of options, Iuiga decided to opt for the home and living essentials category. Electronics, a mass-market product category, was found to be unsuitable as it was highly competitive and saturated in terms of both brands and retailers. Market leaders like Lazada and Challenger pursued aggressive pricing strategies with limited scope for meaningful product differentiation. The product category of mother and baby offered low competition and attracted quality-conscious customers with high spending power. However, it was deemed unsuitable as it comprised a niche market with limited scope for growth and did not enable natural extension into other categories going forward.

Home and living—comprising furniture and homeware—did not have much competition in the Singapore market, and the category was broad enough to enable an umbrella approach and enable an introduction of subcategories within it. Within a year of its launch, Iuiga’s product portfolio expanded to include nine other categories such as lifestyle products, kitchen accessories, furnishings, travel accessories, electronics, and mother and baby.

The true cost of quality

Iugia uses age, generation, lifecycle stage, and lifestyle to define its target audience–millennials and Gen Y in the 25-45 years age group. They are active Internet users who are beginning to set up their own households with a proclivity towards better quality products and value for money. The brand offers these customers a ‘same for less’ value proposition by positioning itself at par with premium brands for its high quality, but selling at much lower prices.

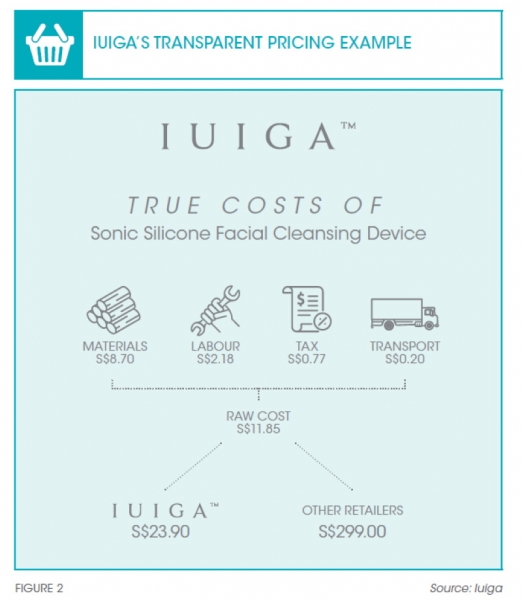

What differentiates the company is its transparent pricing. Iuiga shares a detailed price breakdown for each item on its website and mobile app, including the mark-up it charges (refer to Figure 2). The transparent pricing breaks the assumption that price is a surrogate for quality, and is designed to reveal the huge premiums charged by established brands. Iuiga also differentiates itself from other e-tailers by offering a unique ‘next day’ home delivery service for orders exceeding US$65.

Successful launch

Iuiga’s mobile app and website launches during May-July 2017 were accompanied by offsite activation events at high-traffic points such as hawker centres and commercial centres during lunchtime. People were invited to download the app and visit the website, register and share feedback in exchange for free ice cream. The launch events triggered many conversations on topics such as legal rights versus ethical practices that were captured widely on social media platforms, leading to much-needed publicity for the e-commerce brand. The ensuing debates also provided the company an opportunity to address consumer concerns, quell rumours and share its value proposition effectively. The market response was encouraging with sales taking off at an average of 630 units for the first quarter, and growing to an average of 2,666 units by the third quarter, an increase of almost 320 percent.

The first mover advantage allowed Iuiga to erect high entry barriers for other start-ups in the Singapore market, as its heavy operational model, characterised by high cost of inventory and low margins, demands considerable capital investment and cash flow. Iuiga has since forged close relationships with ODMs of global brands, enabling the company to enjoy highly favourable and unparalleled terms such as a minimum order quantity of only 100 units compared to the industry standard of 2,000 to 3,000 units.

The way forward

The upward sales trend was short-lived and the monthly takeoff began to plateau from the ninth month. Limited brand awareness among Iuiga’s target segment was identified as a key factor behind the slowdown as its presence was solely online in a market like Singapore, where e-commerce penetration was still low. Jaslyn Chan, head of marketing, suggested that Iuiga consider setting up a pop-up store, which could be an effective marketing channel in driving customer engagement. This would also target the large offline consumer market. However, the proposed physical store raised many concerns.

Iuiga’s business model was based on minimising overheads in order to pass on the savings to customers. Going physical meant more investments: leasing retail space, hiring more people, providing training, and cultivating a different skill set, i.e., in-person service. The online medium allowed the company to pursue a low-overhead-cost model and offer attractive prices for high quality products to its customers–its unique selling proposition. Would not the omni-channel platform undermine the strength of Iuiga’s core business model?

Moreover, the e-commerce start-up had an efficient but small team. The brick-and-mortar space was uncharted territory for them. They would struggle in managing both the online portal and the pop-up store. Although the CEO acknowledged the need to accelerate new customer acquisitions, he wondered if it would be possible to convert offline footfall to online traffic. What if the offline engagement did not subsequently translate into online purchases? Was Iuiga ready to bear the operational and financial risks involved?

Using detailed market research and industry experience, Chan listed many convincing arguments for going physical:

Brand building: The offline medium offers Iuiga an opportunity to enhance consumer engagement through tangible face-to-face interactions. The ability to touch and feel helps in minimising buyer dissonance, if any, by letting buyers assure themselves about the brand’s characteristics that are not palpable digitally. Moreover, the retail space acts as the company’s ‘living billboard’ and repeated exposure to it helps build awareness and positive brand associations.7

New customer acquisition: As offline medium commands about 95 percent of Singapore’s retail sales, getting physical may help Iuiga attract a much wider group of its target audience. Customer acquisition for Iuiga online is also hindered by the minimum order size of US$65 for home delivery. First-time customers may not be comfortable with the idea of spending too much on a brand they have not experienced before. A pop-up store would allow them to buy as per their preference, and a satisfactory experience will embolden them to place bigger orders online.

As Iuiga makes it mandatory for all new customers at the pop-up store to first download and register on the Iuiga app, the company can seamlessly transition these customers from offline to online and broaden its customer database for e-marketing.

Cost of brand building and customer acquisition: While the online channel is cheaper with no physical place to rent, no cost of merchandising, no salespeople to employ and no utilities bills to pay for, the e-platform has increasingly become highly competitive and saturated. To be able to differentiate and position itself uniquely, an e-brand has to invest considerably in social media platforms, focused marketing through e-mailers, and advertising on platforms such as Google. On the other hand, an offline store attracts considerable footfall in a country like Singapore where distances are short and people prefer to frequent shopping malls. More importantly, a pop-up store as a semi-permanent space costs only a fraction of a regular brick-and-mortar store. It is a temporary expense and thus should be treated as the cost of marketing rather than a channel for retail.

Invaluable consumer insights and feedback: As offline showrooming allows retailers and consumers to be physically present in the same environment, a retailer is able to assess, anticipate and respond to customer needs in real time. Observing customer behaviour provides meaningful data and opportunities for cross-selling.

Omni-channel customers: Consumers’ paths to purchase have become increasingly non-linear, involving interaction with multiple touch points across both online and offline channels. A customer’s decision-making process includes the following stages: need identification, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision and post-purchase dissonance. For each stage, customers today rely on different channels and expect these to be seamlessly integrated with one another. For Iuiga, opening a pop-up store would be its first step towards catering to the millennial customers in Singapore, who, despite being Internet-savvy with high mobile and digital penetration, prefer to make purchases offline.

Complementary services: A pop-up store can help Iuiga provide a number of customer services that it cannot provide as an e-commerce-only platform such as self-collect, return and exchange of products. With a growing product range, a physical store would also be a much-required additional inventory holding space. Furthermore, instead of stocking the latest designs and products at a warehouse where no one can see them, Iuiga would be able to stock and display new products at the pop-up store for customers to check out and even buy.

The brick-and-mortar option

After carefully weighing all the options, the management team decided to go ahead with the physical retail strategy and within two months, in May 2018, rolled out Iuiga’s very first pop-up store. While there were incremental monthly costs such as rent, labour and utilities expenses, the initial results were encouraging with a healthy growth in the number of customers visiting the store. Total revenues and customers grew over the next four months, although the basket size per customer had decreased. The omni-channel approach seemed to have borne fruit, though there was more needed to be done. Complacency was not an option for Iuiga.

Kapil Tuli

is a Professor of Marketing and Director of the Retail Centre of Excellence at Singapore Management University

Sandeep R Chandukala

is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Singapore Management University

Sheetal Mittal

is a Senior Case Writer at Singapore Management University

References

1. Today, “Asia’s Policy Makers Just Scored a New E-Commerce Growth Measure, Thanks to Singapore”, April 16, 2018.

2. The Online Citizen, “Competition Racks Up in Singapore’s E-Commerce Scene”, August 16, 2018.

3. The Online Citizen, “A Crazy World of Singaporean Online Shoppers: Which One Are You?” October 4, 2017.

4. Statista, “Number of Internet Users in Singapore from 2015 to 2022 (in millions)”.

5. Singapore Business Review, “4.83 Million Singaporeans are Now Online”, January 30, 2018.

6. Go Globe, “Ecommerce in Singapore”, January 19, 2016.

7. Ibid.