A meditation toolkit for business leaders.

Interest in meditation has risen dramatically in recent years, as these practices move beyond ancient monasteries to take root in big cities as well. Hundreds of scientific research studies have provided support for a broad range of pragmatic benefits arising from these practices, such as lowering stress and anxiety, improving emotion regulation capabilities, and developing more harmonious interpersonal relationships. From our research conducted in Singapore and worldwide, we have also witnessed the benefits of meditation in improving negotiation outcomes, leadership skills, work engagement, coping with all-too-frequent interruptions, and ethical decision-making. As a result, many organisations, not only those in Silicon Valley, but also others in traditional industries across many countries, now offer some form of meditation programme to their employees. Given the importance of mental health and well-being, this trend has accelerated as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Headspace, one of the leading mobile applications providing guided meditation, reports that not only have individual app downloads doubled between March and October 2020, but corporate interest in providing employee access to meditation practices via the app has grown by 500 percent.1

Whether you are already a regular meditator or simply curious to learn more, this article provides you with practical, evidence-informed guidance on how and when meditation can be used effectively in the workplace, along with a free toolkit to help you start practising meditation today.

|

ORIGINS OF MEDITATION Meditation refers to a broad range of practices for cultivating different states of mind. One of the earliest historical records of meditation—cave paintings of individuals in meditative postures found in the western part of modern-day India—dates back over 7,000 years, circa 5,000 BCE. Many of the versions of modern meditation originated from the Vedic teachings found in India that were written about 3,500 years ago. These scriptures provide instructions on how meditation is to be conducted, and describe its different forms that have evolved over centuries into the practices presented in this toolkit today. An important distinction needs to between how meditation is described in this toolkit, and how it is viewed in Buddhism and other spiritual traditions. While the practices in this toolkit are predominantly drawn from Buddhist teachings, we focus on using them to develop specific states of mind that are amenable to workplace tasks, similar to how meditation is approached in the scientific community. Alternatively, in Buddhism, the use of meditation is to further individuals’ progress along a spiritual path towards enlightenment and freedom from suffering. Therefore, meditation can be used to achieve different goals. Here, we focus on workplace well-being and productivity. Source: Thomas G. Plante,“Contemplative Practices in Action: Spirituality, Meditation, and Health”, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2010 |

What is in the toolkit?

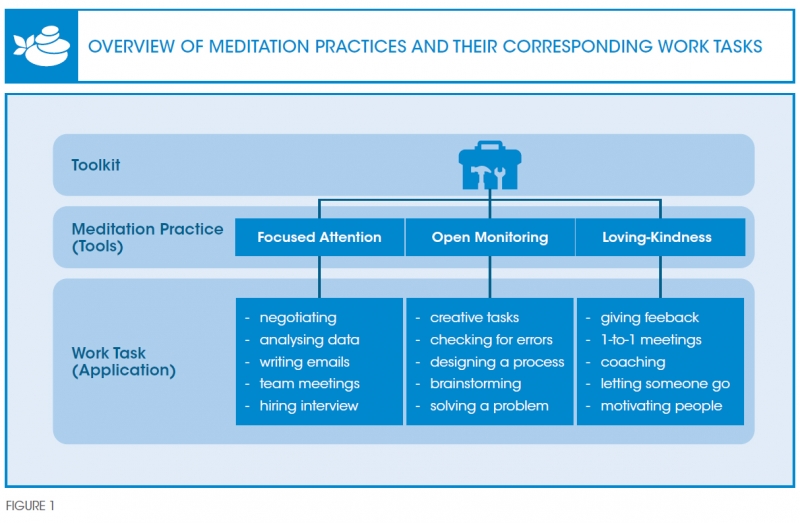

A common misunderstanding is that meditation is simply a method for ‘focusing the mind’, in order to work in a more concentrated and efficient manner. While this perception is not incorrect, it is incomplete. Meditation is not just a single tool for focusing the mind and enhancing productivity. Rather, you can think of meditation as a toolkit of different practices for different purposes. We present three main types of practices in this meditation toolkit, each offering unique benefits at the workplace.

Drawing on cumulative research evidence, this meditation toolkit includes three fundamental types of practice: ‘Focused Attention’, ‘Open Monitoring’, and ‘Loving-Kindness’ meditation. These practices have their roots in contemplative and Eastern spiritual teachings, such as Jainism, Buddhism, Taoism, and the Yoga Sutras. Researchers in the fields of neuroscience, medicine, and psychology have studied each of these three types of meditation extensively. What they found is that each practice activates distinct neurological structures in the brain when practised and trained over time. These findings bridge the chasm between Eastern spirituality and Western science, demonstrating that people can use meditation not only as a valuable component of spiritual practice, but also as a tool to alter how we respond to the world around and within us.

FOCUSED ATTENTION MEDITATION

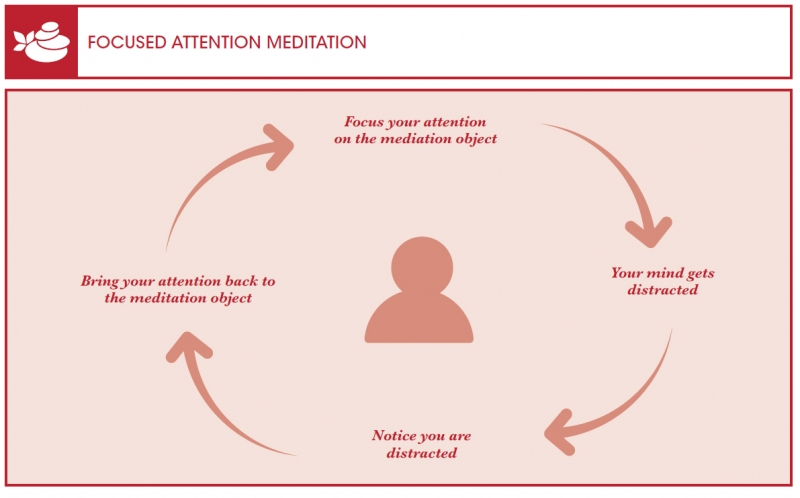

This is probably the most widely known practice and included in most secular mindfulness-based interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Focused attention meditation involves two main steps. First, you select an object for meditation. Second, you keep your attention fixed on this object. The object can take several forms. You could use a specific phrase or mantra as the meditation object to fixate your attention by repeating it silently. Other options include focusing your attention on physical objects, such as a candle.

Another prominent form of practising focuses attention on the sensations of breathing. The breath can be a particularly useful meditation object because it is constantly present and varies naturally, providing rich and ever-changing sensations for the practitioner to concentrate on. Focusing on a steady, slow breathing pattern can bring about a calming and relaxing effect. As a result, breathing has become the most common form of practice for meditation training courses and apps. However, the meditation object is considered less critical to the practice than the mental action of holding one’s attention steadily on it and gently bringing the mind back to the object when thoughts stray.

This meditation practice helps you hone the important skill of remaining focused on a single object for prolonged periods of time. It has been found to increase the activation of brain regions associated with attention control. As such, you may use this practice to improve your performance at sustained-attention tasks and convergent thinking (i.e., tasks that require careful deliberation and logical ‘vertical’ thinking, as opposed to creative, outside-the-box ‘lateral’ thinking). In sum, the state of mind cultivated through this practice is a focused mental state.

OPEN MONITORING MEDITATION

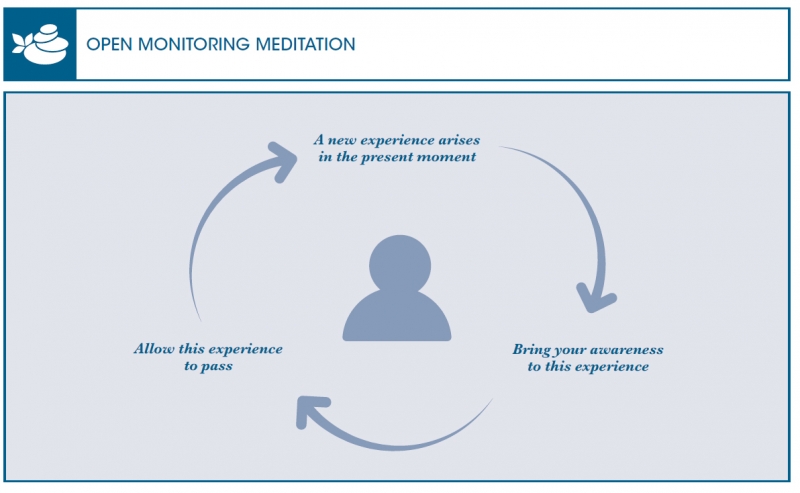

This meditation practice has been receiving growing interest and is also included in most mindfulness-based training programmes. In open monitoring meditation, you broaden your attention and are encouraged to bring a non-judgmental awareness to the thoughts, sensations, feelings, and action impulses arising in the present moment. When practising, you observe your experiences without judging (i.e., without categorising the experience as either good or bad), rejecting, or clinging as they arise, become present, and fade away naturally. To begin the practice, you could start by gently quieting your mind with a few deep breaths. Next, you would begin to broaden your attention to notice sounds (e.g., bird song), bodily sensations (e.g., warmth), thoughts (e.g., ruminations about the past), emotions (e.g., joy), and action impulses (e.g., an urge to check your mobile phone) arising in the moment. By just observing the experience as it is, practitioners practise letting the experiences come and go naturally, and at the same time gain insight into the causes and flow of these experiences.

Open monitoring practice can be challenging at first because it does not provide you with a specific mental anchor, making it easy for the mind to wander and drift away. To counteract this, practices frequently focus on one domain of experience such as sounds, bodily sensations, and thoughts. Open monitoring practice trains your capacity to become aware of different experiences arising and falling away, while cultivating a non-judgmental and accepting attitude. Research has found this practice to bolster one’s capacity to detect hard-to-see errors, as well as support divergent, out-of- the-box thinking in tasks that require creativity. Based on these findings, open monitoring meditation fosters an aware and noticing mental state.

LOVING-KINDNESS MEDITATION

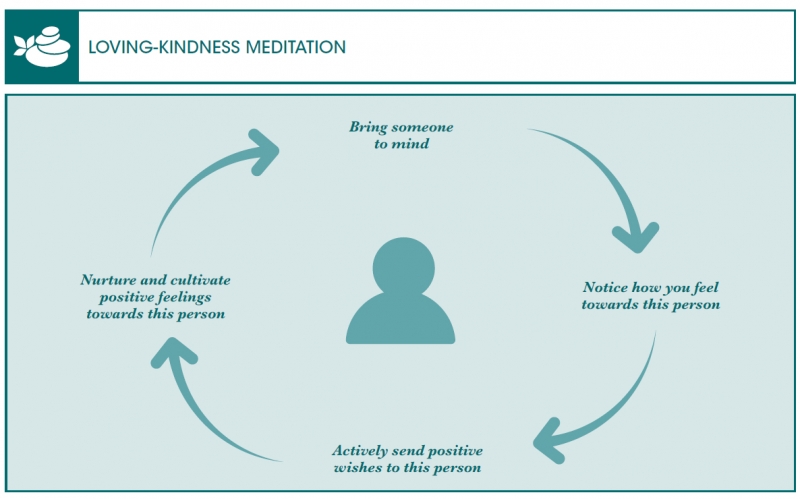

To date, loving-kindness practice is least used in organisations, potentially because of its seeming contradiction with the cut-throat world of business. This meditation practice differs from the previous two in that it does not focus on cultivating a specific attentional state. Instead, as a practitioner, you cultivate a particular emotional state. ‘Loving-kindness’ refers to a feeling of non-romantic, benevolent, unconditional love. As such, loving-kindness can be directed at other people or groups, yourself, or the natural world.

To practise loving-kindness meditation, you first identify the feeling of loving-kindness by visualising someone or something you feel deeply towards. You could imagine seeing or embracing a loved one like a family member or a beloved pet, and then notice what seeing or embracing this loved one feels like, and what it feels like to wish that sentient being happiness and well-being. You focus on experiencing this positive feeling of non-romantic loving-kindness. As you familiarise yourself with the emotion, you practise further cultivating this feeling within yourself. Second, you now try to cultivate this same feeling towards people or things you would not naturally feel loving-kindness towards. You could deepen the practice by thinking of a stranger (or even an enemy) and reproduce the loving-kindness initially cultivated towards a loved one for this other party. Third, the practice culminates in attempting to feel loving-kindness for yourself. This practice can be challenging initially, especially when considering an enemy or yourself as the target of loving-kindness. However, prominent meditation researcher Richard Davidson notes that this practice often has the greatest impact on an individual’s behaviour and well-being amongst the different meditation practices.2 Research has found this practice to promote social connectedness, altruistic behaviour, and self-compassion, as well as reduce racial/political biases, and improve ethical work behaviour. Based on these emotional and interpersonal benefits, loving-kindness meditation generates a caring mental state.

How to use the toolkit

In order to use this toolkit effectively, you need to follow three steps: first, identify your goals; second, select the appropriate meditation practice from the toolkit; and third, apply the practice effectively.

First, you must identify your goals, which could be based on specific task demands and outcomes, or your personal preferences. For example, your goal might be to prepare for an important meeting in 30 minutes. Second, you select the task-appropriate meditation tool. Third, you apply the chosen tool effectively. Here is a real-world example: before Steve Jobs presented a new product, he would always do a focused attention meditation. Why this type of meditation? Jobs likely felt that it was most important to have a focused mental state during the presentation. Likewise, you should also identify your work goals and select the appropriate meditation practice. If your goal is to resolve conflict between two co-workers, it requires you to provide an unbiased assessment of the situation and treat each colleague fairly. Research has found that a loving mental state can reduce bias, promote ‘ethical enhancement’, and increase compassion towards others. Therefore, within the toolkit, loving-kindness meditation would be the best practice for this goal. Figure 1 provides an overview of recommended practices for several common work tasks. Of course, our recommendation is meant as a guide, not a rigid prescription. The best approach is for you to experiment with the practices in the toolkit, and make them work for your tasks and challenges.

Meditation can be used to elicit specific results. For example, it can facilitate effective task-switching. In the modern workplace, we typically encounter manifold tasks with varying demands in quick succession. You might need to move quickly from a brainstorming session (requiring divergent, creative thinking) to a 1-to-1 meeting (requiring interpersonal skills, such as empathy). Making these fast switches can be extremely challenging. However, by taking time for a brief meditation, you might be able to swiftly shift into an appropriate mental state, instead of simply rushing from one task to the next, potentially still being distracted by what you were doing before. For example, you could practise an open monitoring meditation before the brainstorming session and then do a loving-kindness practice prior to the 1-to-1 meeting.

You can also use these practices within your team and the organisation as a whole. By practising in groups, you can support yourself and your staff in developing mental states that match task demands. (For instance, Rakuten CEO Mickey Mikitani recently got all the members of his executive team to practise a focused attention breathing meditation together before each team meeting to start the day fully present and attentive.) By doing so, you can help the team become more aligned so that it can work in unison towards organisational goals.

How to not use the toolkit

Even a good toolkit can do a bad job if used in an unskilful manner. We describe four key misapplications and misconceptions below.

First, meditation is not a magic pill. It cannot solve all problems for all individuals across all situations. The meditation tool chosen must match the goal at hand. A goal-tool mismatch may cause adverse effects. For example, research has found that open monitoring meditation can have a negative impact on motivation. This is a case of a tool misapplication due to the lack of fit between the practice type and its desired outcome.

Second, avoid preaching. Some people may be convinced, perhaps from their own experience, of the value of a meditation practice. However, we should avoid preaching to staff about the merits of meditation. It is impossible to force people to meditate. Even though an employee might sit still, he or she might be doing something else mentally. If you are interested in using this toolkit, we suggest you start by using the tools yourself. If you feel that you benefit from it, you could then tell your colleagues and staff about meditation and this toolkit, and allow them to make their own decisions.

Third, this toolkit does not in itself offer a transformational change. In their book Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body, Richard Davidson and Daniel Goleman describe how meditation practice can lead to neuroplastic changes in the brain, and be a powerful treatment for numerous clinical conditions such as depression and anxiety.3 Such lasting, transformational changes are possible, but only through long-term training over the course of months and years. If you are interested in such longer-term effects, you and your staff could pursue validated meditation training programmes such as MBSR, Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC), and Mindfulness-Based Strategic Awareness Training (MBSAT). These courses have helped people across the globe start and maintain their meditation and mindfulness practices. However, generating these transformative long-term changes is not the purpose of this toolkit. Instead, it is intended to produce localised changes in your current mental state that will help you reach specific goals, such as being present and attentive during a meeting. Whilst repeating these practices will improve a practitioner’s capacity to get into this state, the toolkit alone is not meant to enact deep personal transformation. For such goals, you may want to participate in the training programmes described above, or approach appropriate medical professionals.

|

HOW TO GET STARTED Part of the allure of using meditation in an organisational setting is that it is easy to get started. On-the-spot meditation at the workplace requires relatively little time–as little as two to five minutes. Meditation can also be conducted with audio guidance, making it more accessible to beginners. In order for you to get started straightaway, we have made each of the meditation practices in this toolkit available at the Mindfulness Initiative @ SMU (https://business.smu.edu. sg/mindfulness). We have used these tools in our research with organisations with positive effects, and believe this toolkit can help improve how organisations operate, one meditation at a time. |

Fourth, as a new practitioner or someone interested in starting a meditation practice, you should know that meditation, while simple, is not easy. It is common for beginners to be shocked by how hard it is to keep their attention focused on the present and follow the guidance, even for a short time. This is normal. Just like training at the gym, or learning a new sport or skill, meditation is difficult at the beginning, but will become easier over time. If you find this hard, it probably means your mental ‘muscles’ are less well-developed, so the more you meditate, the more your mental ‘muscles’ will benefit from it. When meditating, leave perfectionism at the door. Just practise, be patient, and trust the process.

Finally, be persistent and remain flexible, as meditation requires discipline. The more you are able to form a habit (e.g., practising before each meeting), the greater the benefits will be. However, persistence does not equal rigidity. As everyone is unique, the toolkit should be used flexibly to fit the idiosyncratic needs and characteristics of different people. If, for example, you experiment with a different practice one day and find that the loving-kindness meditation in fact helps you remain focused and kind when responding to emails, then this tool can be repurposed. Similarly, if combining two of the tools (e.g., open monitoring and loving-kindness) enables someone to be in the best mental state to remain open-minded and compassionate on the job, then this should also be allowed. In sum, people ought to stay flexible, curious, and observant of their internal states and environment.

Future of the toolkit

While this article focuses on the three forms of meditation practice, it is by no means an exhaustive list. As research continues to evolve, there will be updates that can enrich this toolkit in the future. Research in this field is moving at a quick pace and as it does, additional benefits of these practices are being uncovered. Equally important, scholars are also beginning to better understand the situations in which these meditations are not useful, or might even have a negative impact. Like all good toolkits, these meditation tools will have to be fine-tuned.

Ultimately, this meditation toolkit aims to use evidence- based practices to support business leaders and enhance their teams’ capacity to work effectively and collaboratively.

Theodore C. Masters-Waage

is a PhD student in Organisational Behaviour and Human Resources at Singapore Management University

Eva K. Peters

is a PhD student in Organisational Behaviour and Human Resources at Singapore Management University

Jochen Reb

is Associate Professor of Organisational Behaviour and Human Resources, and Director, Mindfulness Initiative @ SMU, at Singapore Management University

References

1. Ari Levy, “Companies are Offering Benefits like Virtual Therapy and Meditation Apps as COVID-19 Stress Grows”, CNBC, October 10, 2020.

2. Daniel Goleman and Richard J. Davidson, “Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body”, Penguin, 2017.

3. Ibid.