How Singapore’s Tan Tock Seng Hospital had to strike a balance between reducing business-as-usual services and increasing outbreak-coping capacity when Covid-19 broke out.

The global pandemic has strained healthcare systems around the world, yet some providers have been able to adapt better and more swiftly than others. One such example is Singapore’s Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH). When Covid-19 broke out, TTSH had to strike a balance between reducing business-as-usual (BAU) services and increasing outbreak-coping capacity. The latter meant that the hospital needed to build isolation rooms, and effectively ramp up its intensive care unit (ICU) capacity and capabilities to adapt to a rapidly evolving global pandemic. Furthermore, hospital management had to make an active push towards ensuring adequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), given the global shortage and uncertainties over the duration of the pandemic. So how could a healthcare organisation that typically prioritises reliability and safety manage to adapt so nimbly to the Covid-19 crisis?

If we look closely at TTSH, we will find that the answer lies in a very different healthcare management orientation: one that is focused on innovating with an agile mindset. This orientation was not implemented overnight, but cultivated over the years through a multitude of initiatives led by the Centre for Healthcare Innovation (CHI).

The Centre for Healthcare Innovation

Like many other developed countries, Singapore’s demographics indicated a looming challenge with an ageing population, hence the government and the management of TTSH set out to drive greater innovation in the healthcare system. One of their initiatives was launching CHI in 2016 to innovate system-level solutions, as they had recognised that initiating a piecemeal innovation programme to make improvements was not going to address the holistic changes needed.

Before the launch of CHI, quality, safety, and improvement had operated in silos with different departments independently overseeing domains of improvement. Thus, systemic changes could only be implemented through incremental improvements at that time. CHI was established to radically alter the way TTSH innovated. It aimed to address two imperatives: first, changing care models to mitigate the challenges of an ageing population, and second, preparing a workforce to be more agile and digitally dexterous with transdisciplinary skill sets.

Setting up a special centre that focused on innovation may seem like an easy way to drive change. However, it created several challenges that are associated with embedding change inside the organisation. While there was an initial focus on innovating through technology, it was soon recognised that technology alone would not help transform the entire system as desired. Rather, a systemic shift could only occur through fundamental changes in TTSH’s human capital system, which would drive a culture that encouraged cross-departmental collaboration and experimentation, without neglecting its emphasis on reliability and safety.

A human capital system approach

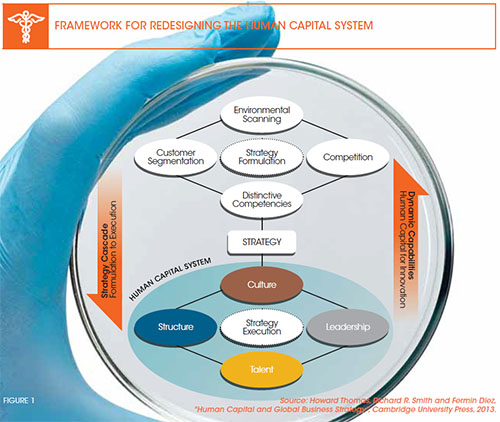

Similar to many hospital systems, there are distinct departments, wards, and areas within TTSH, so large-scale innovation would naturally be limited by these demarcations. To enable a systemic approach, the leadership wanted to shift staff’s mindset from focusing on piecemeal process improvements to embracing innovation that cuts across the entire organisation through cross-departmental collaboration. This shift from the traditional healthcare mindset of concentrating on safety and care to being more open to innovation and risk-taking was initially perceived as contradictory by the staff and medical personnel. The leadership team addressed this misperception by redesigning the hospital’s human capital system to enable its staff to see that safety and innovation are interdependent, rather than contradictory, objectives. This redesign of TTSH’s human capital system revolved around four pillars: leadership, structure, talent, and culture (refer to Figure 1).

LEADERSHIP SUPPORT

The leadership team across the hospital was asked to step up and participate in a number of innovation initiatives across various areas. Senior management were recognised for rolling up their sleeves and working alongside the ground staff in running projects. For example, senior hospital leaders were encouraged to perform regular quality and safety walkabouts around the hospital. As a result, they gained insights into the operational realities, which helped them to better empower staff to undertake innovation projects that improved patient and staff safety. CHI supported these projects by providing physical innovation spaces, methods, and tools, along with measurement systems.

TTSH CEO Dr Eugene Fidelis Soh promoted the collaborative innovation culture actively. Besides being part of the teaching faculty for improvement and innovation, he also commissions education in technology, automation, and robotics, and chairs the Robotics Committee at Singapore’s Ministry of Health. In addition, he started the Voices 9000 platform to engage directly with staff. This platform allowed him to have direct ‘skip level’ conversations with staff, which would not have been possible otherwise, given typical bureaucratic constraints. It also provided him with an opportunity to engage them on hospital strategies and address their concerns. By August 2020, more than 7,200 staff had participated in these conversations, and issues that had been identified included working hours and conditions. Soh also received a number of ground-up suggestions for workflow improvements.

In another initiative, a key programme to take the hospital’s leadership to the next level, called ‘Engaging Leadership’, was conducted for 120 senior leaders. This programme became a central catalyst for CHI as it helped align leaders across the board to the hospital’s innovation focus, tools, and methods. It was more than just a training effort, as it also included follow-up sessions with assigned external coaches and mentors.

ORGANISATION STRUCTURES

CHI was designed to encourage collaborative innovation by creating physical space and breaking down traditional structural limitations. The CHI Living Laboratory (CHILL) provides a makerspace for medical practitioners to learn about new technologies in the digital and 3D printing domain, and conduct lessons in design thinking and prototyping. This complements the Innospace facility that supports project teams that apply lean innovation in their projects. Meanwhile, Marketplace and Kampung Square are open spaces for staff and students, and TTSH partners, respectively, to interact and discuss ideas. The centre also houses the Command and Control Centre (C3), which acts as the ‘brain’ of the hospital, managing the flow of people and inventory across the entire campus.

Another way of structuring collaborative exchanges of ideas to foster innovation came about through CHI Innovate—the centre’s flagship annual conference for co-learning, an event that brings together thought leaders from various industries across the globe. Other initiatives include CHI Learning and Development, an online platform for sharing best practices with partners. The centre has also initiated plans for a CHI Start-up Enterprise Link to facilitate engagement with health tech start-ups and suppliers for the procurement and use of commercially ready products in a real-world clinical setting.

TALENT MANAGEMENT

In 2011, TTSH launched the “Better People, Better Care” slogan to address the people-side of healthcare support. It emphasised the importance of staff as a critical driver of TTSH’s innovation journey, and Soh took personal responsibility for managing the talent pipeline within the hospital.

The centre also played a key role in developing talent by organising opportunities for learning about innovation tools and processes through informal brownbag sessions, and formal masterclasses led by agencies such as Design Centre Singapore. Over 80 percent of the staff have been trained in innovation and improvement tools, and over 70 percent have participated in at least one improvement activity. Furthermore, staff are regularly sent to different parts of the world to participate in conferences and seminars to gain first-hand insights into innovation in other healthcare systems. CHI also funds the training and development of clinician-innovators through the CHI Fellowship, a 16-week programme taught by a panel of local and international faculty to better equip young aspiring leaders from clinical, administration, and operational units that undertake system-level innovation and improvement projects.

ORGANISATION CULTURE

While there had been a focus on continuous improvement through standardised processes and protocols for evidence-based care delivery prior to 2011, these improvements tended to be confined to silos with few instances of innovation that cut across departments, functions, and roles. To facilitate the transition in culture towards adopting broader collaborative innovation thinking, the management shifted the focus on quality improvement towards achieving broader organisational outcomes, such as making TTSH a great place for healing (patients) and work (staff). After establishing a common vision, it then actively sought to encourage collaboration, and CHI became a central part of this shift by allowing collaboration through innovation projects and learning.

These efforts included attempts at providing physical and virtual spaces, and scheduling time for collaborative exchanges of ideas. Additionally, numerous initiatives were put in place to cultivate a sense of collegiality. For example, TTSH embarked on an onboarding programme, which is owned and conducted by the senior leadership team, with the sole objective of building a kampung (Malay for ‘village’) culture, on the basis that ‘it takes a village’ to accomplish broad common goals. Staff were trained in techniques to increase engagement and conversations across ranks by building psychological safety into in- group interactions. A social integration fund was set aside to encourage staff to get together and build stronger interpersonal bonds.

This spirit of collegiality was reinforced by the management’s adoption of a ‘listening ear’ to move away from the traditional top-down, centralised approach to address staff’s concerns, to a bottom-up approach that blurred the vertical boundaries between management and staff. This collaboration was fostered in part by CHI, as innovation efforts required a more holistic approach across boundaries.

Together, this four-pronged approach of working on the leadership, structures, talent, and culture pillars created an internal system of human capital that reinforces innovation. Every two years, TTSH measures staff engagement and takes remedial actions to address workforce concerns, identify ongoing improvement areas, and groom engaging leaders who can lead the transformative work. In addition, efforts to align the internal human capital system are ongoing and constantly reviewed.

An external partnership network approach

In the early days of innovation and improvement work, teams were formed to address a problem statement without including the upstream and downstream process owners—not to mention the consideration of external stakeholders. This posed a huge obstacle to the efficacy and sustainability of its improvement work on the hospital.

To address healthcare more holistically, TTSH recognised the need to tackle many of the challenges together with society at large. Over the last few years, CHI has established 39 co-learning partnerships at multiple levels: local and international partners from the healthcare and healthcare innovation domains, academia, the health technology industry, as well as agencies for design, workforce, and leadership. By bringing together other stakeholders and thought leaders, it has been able to conduct innovation clinics, masterclasses, and programmes to develop improvement and innovation practitioners and faculty. This external network is continually working together with TTSH/CHI to think differently about healthcare and the needs of society, both now and for the future.

The Covid-19 test

TTSH, together with the 330-bed purpose-built National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), accounted for the majority of hospitalisations during the Covid-19 pandemic and was the first site to respond to a surge in demand for capacity to treat patients. Thereafter, another 100-plus beds in the main building were allocated to meet the high national demand.

While the pandemic was still unfolding, the hospital developed a response plan to address the uncertainties surrounding the pandemic and refocused and shifted its BAU services. For example, clinics cut BAU services by 40 to 60 percent to free up resources for supporting Covid-19-related work. Clinical staff were put on roster to undertake virus-screening duties. The now-decommissioned Communicable Disease Centre (CDC) 1 was re-equipped and activated as an isolation facility. As one of the immediate risks was that numerous healthcare workers could get infected, the need for separation, containment, and scheduling was prioritised. The hospital activated staff to be part of the community Covid-19 screening effort, while others helped to plan for various scenarios, based on the latest developments.

One of the potential scenarios unfortunately turned into reality when the virus spread to the foreign worker dormitories in Singapore. The exponential rise in the number of cases, from double-digits to over a thousand a day when the outbreak was at its peak, required further conversion of wards and allocation of ICU beds to manage the growing number of Covid-19 patients. The most significant challenge was ensuring sufficient resources for patients needing oxygen.

Given the trends observed in other parts of the world, it was expected that the ICU resources would be significantly stressed by May 2020, so TTSH more than doubled its ICU capacity, and trained nurses and doctors to do intubation procedures. More importantly, the flexibility and adaptability of the staff, particularly nurses, enabled NCID to double its capacity in the space of a few weeks, to meet the surge in demand during the initial phases of the outbreak.

While the pandemic is far from over, it is clear that CHI played a crucial role in enabling TTSH to respond nimbly to the Covid-19 challenges. The ability of the entire system to work together when dealing with problems, and a systems approach to the hospital’s internal human capital, coupled with a network approach to external partners, has served the organisation well throughout the pandemic thus far.

Lessons for healthcare providers and others

The focus on creating an agile organisation with a strong focus on innovation is not new in tech-oriented businesses, but is rather rare in the heavily regulated healthcare industry. Reflexing on TTSH’s journey, there are five notable takeaways.

1. Commit to the Innovation Journey

Embarking on an organisation-wide innovation journey is an expensive proposition. The hospital’s initiative was made possible through a generous donation from the family of the late Ng Teng Fong to establish CHI. Over time, financial and cross-sector support from other stakeholders further bolstered the process. Hence, before an organisation starts such a journey, it is critical to have the resources, stakeholder support (particularly that of the regulator), and the entire ecosystem prepared, aligned, and committed to the cause.

2. Reconcile Innovating with BAU

When management tried to promote an innovation mindset, staff often questioned why they should invest their time and resources in changing how they operate when they are already stretched. TTSH’s management reconciled this apparent contradiction by emphasising on the interdependence, rather than on the trade-off, between these priorities. Innovating radical solutions is critical to maintaining BAU—this point was reinforced when the entire organisation had to develop new solutions and procedures to cope with the demands of the Covid-19 crisis. In areas where they could not be compromised, such as patient safety, management ensured that innovation was ring-fenced from clinical settings until safety and reliability could be demonstrated.

3. Take a Systems Approach to Human Capital

While many traditional organisations attempt to introduce innovation, few could build the drive for innovation into their culture. This requires a systems view of the behaviours expected, which is shaped by leadership, organisational structures, talent management systems, and culture.

4. Embrace External Networks through Partnerships

Healthcare organisations do not sit in isolation, as they depend on the ecosystem of the local government, social services, education providers, and other sectors for success. To bring about innovation, it is necessary to bring these stakeholders together, and foster collaboration toward common goals and objectives. This not only sparks innovation, but also enhances the overall view of system- related issues and challenges.

5. Be Ready for a Test

Too often, leaders and stakeholders will revert to their old ways when confronted with a crisis. Putting confidence in the system and being able to put it to the test might help move things in the right direction, and find new opportunities for learning.

TTSH has been successful in spurring innovation through CHI. Covid-19 has, however, led it to put numerous key initiatives on hold. This test serves as a reminder of the importance of its mission that is grounded in quality healthcare today, with an eye towards better healthcare for society in the future.

Kenneth T. Goh

is Assistant Professor of Strategic Management (Education) at Singapore Management University

Richard R. Smith

is Professor of Strategic Management (Practice) at Singapore Management University

Cher Heng Tan

is Deputy Clinical Director of the Centre for Healthcare Innovation and Assistant Chairman, Medical Board (Clinical Research and Innovation) at Tan Tock Seng Hospital

David Dhevarajulu

is Executive Director of the Centre for Healthcare Innovation