Globe Telecom—a major telecommunications service provider in the Philippines—had a long, pioneering history in the communications business. Incorporated in 1935, it was the first international wireless communications company connecting the Philippines to the rest of the world. Years later, in 1994, Globe would become the first company in the country offering mobile subscription-based services.

By 2018, more than half of the Philippines’ 100 million residents were Globe customers, with the company as the market leader in both postpaid and prepaid segments. Service revenues were up nine percent from over a year ago. For an industry that was only growing by two to three percent, it meant that Globe was chipping revenue out of the competition. The results were so impressive that Citi, in its 2nd Quarter 2018 Results Report, noted, “Globe hands down delivered the best performance amongst the ASEAN telcos in 2Q…”

But the company was not always so well-positioned. Despite its first-mover advantage, Globe had found its market share steadily eroding, and by 2010, its market share had shrunk from 42 percent to 33 percent in just under six years. Morale within the company was at an all-time low, and the workplace had become toxic. Globe was clearly failing in the execution of its strategies, and also did not appear to have the right capabilities to conceive effective ones. From these depths, how did the Globe leadership team succeed in dramatically turning the company around? What did they do to grow beyond the traditional telco business model and transform every aspect of the company to become a provider of digital lifestyle, the prized market leader and an iconic brand in the Philippines today?

Diagnosing the problem

The deregulation of the telecommunications industry in 1995 saw the creation of several wireless service operators. Prior to this, the sole provider of telecommunications services in the country was PLDT. In March 2000, PLDT acquired one of the operators, Smart Communications. And while Smart and Globe would prevail as the leading mobile operators, the former had the advantage of network footprint and distribution pervasiveness. In no time, Smart aggressively penetrated the mass market via prepaid. Globe, on the other hand, was strong in postpaid. Prepaid, however, had a larger market, as the majority of Filipino consumers preferred ‘sachet, a-la carte’ plans, as opposed to committing to the higher upfront price of the postpaid subscriber plans. Smart, therefore, remained the mobile market leader for a long time, with Globe coming in second.

In 2003, another operator, Digitel Mobile, launched wireless mobile services under the Sun Cellular brand. In October 2004, Sun started offering unlimited calls and texts. The first of its kind, the campaign proved effective and Smart and Globe followed suit. In this scenario, the size of one’s subscriber base played a critical role, as unlimited promotions only applied to same-network calls and texts. Leveraging the scale of its subscriber base, Smart continued to grow. And as Sun started gaining traction, it was Globe who started losing market share.

The years 2004 to 2010 saw a steady decline of Globe’s market share. To make matters worse, in 2011, PLDT acquired Sun Cellular, resulting in the former controlling almost 70 percent of the subscriber base. In the era of calls and texts, it was simply too hard to break the ‘calling circle’. Having determined that the company was desperately in need of a transformation, and that the country was on the cusp of a new wave—the coming of smartphones and data—redefining the company had everything to do with the next phase.

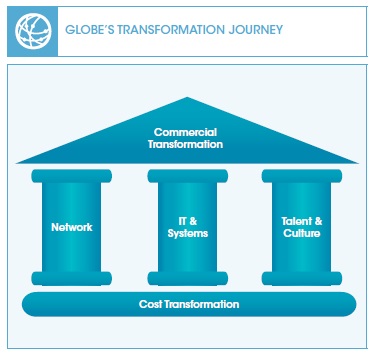

The Transformation House

The Globe leadership team recognised that it would need to transform its commercial offerings if it was to survive—not only that, it also needed to position itself anew to stay abreast of, or at least keep pace with, other players.

Globe’s network was a generation or so behind the competition’s technology. The company was saddled by legacy IT systems, prohibiting it from offering new in-demand products and services without significant investment; a hard sell to investors already wary of past performance.

Spearheaded by Ernest Cu, who had joined Globe in 2008 as the Deputy CEO and subsequently became President and CEO in 2009, ‘The Transformation House’ was Globe’s answer to meeting the competition head-on—a framework to systematically address these challenges by focusing on three pillars: Network; IT and Systems; Talent and Culture. Investment into these pillars proved essential to transforming Globe’s commercial offerings into an ever-growing array of sophisticated products and services supported by high-tech capabilities and entrepreneurial competencies.

NETWORK

The senior leadership at Globe mulled over how to address its ageing infrastructure. On the one hand, they could focus on simply expanding coverage with the existing network and incrementally upgrading or augmenting the equipment. On the other, they could take it all down and replace it. The leadership team decided on the latter, at a cost of a billion US dollars. This was underwritten by the Ayala Corporation, the oldest and largest conglomerate in the Philippines (which had a 30 percent stake in Globe); and the Singtel group of companies, one of the largest telecom groups in Southeast Asia (with a 40 percent stake in Globe).

At such a high price tag, the investment needed to be more than a one-time fix. Cu described this move, “It is almost like changing the engines, the wings and navigation system of a commercial airplane at the same time—while in flight and carrying passengers.”

In 2010, Cu decided to adopt a single vendor policy, an unprecedented move in the industry at that time. Previously, Globe relied on four different equipment and infrastructure suppliers, Cisco, Nokia, Ericsson, and One Way. Under the new policy, Globe and its new vendor-partner were better able to manage the modernisation effort, which began in 2011. This relationship would also make continued maintenance and improvement of the network more efficient and cost-effective.

It was a prudent move. Halfway through the modernisation programme, Globe recalibrated from a 3G to a 4G LTE network in response to growing consumer appetite for data-hungry apps, and cheaper, next-generation smartphones.

Globe also continued to expand its coverage area, a feat in-and-of itself given the 7,000-plus islands that constituted the Philippines; a major differentiation point from its competitors, which tended to be more concentrated in major population centres.

IT AND SYSTEMS

IT business and operating systems are complicated. Take for example, the prepaid model. In order for this to work, a telco needs to be able to track, in real time, millions of different account-linked devices. The mobile phone was in effect a wallet; when a customer responded to an SMS promotion offering five hours of talk or data, Globe needed to be able to deduct that from the account and track usage 24/7.

Ultimately, Globe invested more than US$400 million into its IT systems—with capabilities beyond just billing and business support. Customer analytics and usage tracking allowed Globe to gain valuable insights into where, when, and how customers were using their phones. This capability was a key competitive advantage in understanding, anticipating, and delivering on customer needs.

Cu explained, “We compete on product, marketing and quality of network as opposed to price. Globe has never been a price leader. We believe that the combination of the things we do draws the customer to our service more than other brands.”

TALENT AND CULTURE

With the transformation of its IT business and operating systems, Globe was able to innovate and create products faster, be first to market and change the whole customer experience from a utility to a customer-centric brand of service. However, all of this required putting the customer first and transitioning out of a ‘utility’ mindset. It had to be ingrained in the company’s DNA, its mission, vision, and values—the ‘Globe Way’.

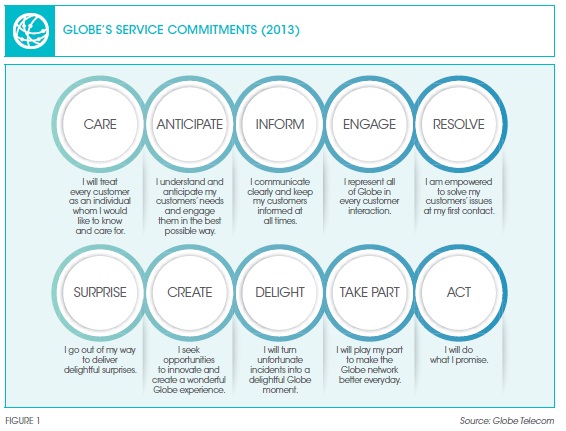

The ‘I Love Globe’ campaign redefined Globe around 10 service commitments that were shared across the entire organisation. To put customers first meant to continuously engage with them, and to see them as more than subscribers. This mindset had to be pervasive. For leadership and management, it also meant continuous engagement with employees. By better knowing and understanding the needs and aspirations of both customers and employees, Globe would be more able to satisfy those desires. This meant becoming more than a telco, and in 2013, the company redefined its Service Commitments to enhance clarity on how the company would engage with its customers (refer to Figure 1).

Globe’s reimagined, redesigned stores were a case in point. Initially, they resembled something more akin to a business or service centre where customers would visit to pay bills and report problems, rather than a place to browse and experience the new technologies being offered. Long lines and a ticket queue system that kept customers waiting was a poor brew as unhappy customers had been running into employees with low morale—which was certainly not reflective of the aspirations of the Filipinos.

As management began to reimagine the retail points of contact, there was an immediate desire to reduce waiting time as a first step to improve service and empower employees. But at its core, this goal in some ways missed the great opportunity. To elaborate, while most retailers were trying to get people into their stores, here was Globe trying to get them to leave! The management quickly realised that while in the store, customers wanted to try new technology, talk with consultants about the products, and get a quick update on the latest and greatest. Hence, while the first generation stores had plastic dummy phones that frustrated would-be shoppers waiting for their turn in line—today, the third generation stores are built around experience zones designed to showcase technology, merchandise and integrated service offerings. The slick, redesigned retail outlets are now state-of-the-art and very attractive showrooms where potential customers can experience the digital lifestyle Globe had to offer.

The Globe leadership team thus did not stick to the current practices, but became highly innovative. They would break the ‘rules’ because they thought that it was the right thing to do for their customers and employees. Globe received the Gold Stevie Award in 2018 as ‘The World’s Employer of the Year in the Telecommunications Industry.’ In the same year, Globe also bagged the ‘Best Workplace in Asia’ award at the Asia Corporate Excellence & Sustainability Awards. Cu commented, “I am happy that our efforts to create a great workplace have been recognised. We built a new way of working, a work environment that promotes a culture of empowerment, so good ideas don’t get trapped by hierarchy.”

Transforming commercial offerings

It was clear early on that data was going to be the key to the future—which itself presented a fundamental challenge because many disruptive services would end up flowing through a telco’s network. For example, internet-based messaging services like WhatsApp could easily disrupt the SMS messaging services offered by Globe. The risk was that by becoming a provider of data, Globe could become commoditised, competing purely on price. The key strategy was to keep a focus on changing consumer demands.

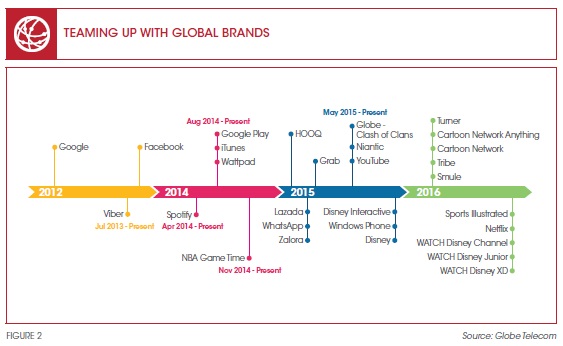

The alternative was to become a purveyor of the ‘digital lifestyle,’ and not just a purveyor of data. To do this, Globe began leveraging its position within the digital ecosystem by partnering with potential disruptors in order to avoid getting stuck as a ‘utility’ and to be able to offer a wider portfolio based on its customers’ varying interests.

Globe presented itself as a valuable partner when it teamed up with Spotify and later Netflix, among other leading online media companies, by explaining how they could help grow each other’s businesses by changing customer habits. For example, rampant online piracy had led Filipinos to become accustomed to not paying for content. To overcome this, Globe needed to demonstrate greater value in paid-for content. So a Spotify premium service anywhere else in the world would probably cost about US$10 a month, but through Globe, it was about US$3 a month.

In addition to the ‘discount priced’ model, Globe also came out with a ‘freemium’ construct, whereby consumers could try services for free for the first few months. Designed for maximum habituation, the consumers’ journey went through the phases of awareness, trial, and adoption. They began to value on-demand streaming as a superior product to pirated material, which tended to be more inconvenient to access and of lower quality.

That initial transition was also a significant leap for consumers; by introducing them to the expansive libraries of Spotify and Netflix at a discount, they became better engaged with both the streaming service and the mobile device—which resulted in higher rates of data usage than they would have otherwise consumed.

Bolstered by the success of these and other media content partnerships, and recognising a significant gap in local content, Globe Studios was created. In the Philippines, local content was controlled by the incumbent networks and not easily shared with other OTT1 services and apps. So Globe has attempted to stimulate local content production by collaborating with other film producers to create and promote Filipino content for national and worldwide distribution. One of their productions, Bird Shot (2016) was selected as the Filipino entrant to the ‘Best Foreign Film’ category at the Academy Awards and was the first Filipino movie to be shown on Netflix.

Globe’s endeavour to bring Filipino talent to the world stage does not stop at film. The company also aims to support the fashion, music, and theatre industries—areas of the creative arts where Filipinos have the potential to excel.

Future-oriented

Globe’s commercial challenges in the late 2000’s afforded the company an important insight beyond just the dangers of complacency. What it came to learn was that the value of its enterprise was not in providing bandwidth alone—that could be commoditised—but in facilitating the digital lifestyle; as an exclusive branded channel that was fundamental to its customers’ lives.

Never to be out of touch with the zeitgeist, Globe has entered into the next stage of the consumer digital lifestyle. Through its fintech arm Mynt, and by partnering with Ant Financial, Globe is leveraging its trusted brand, customer accounts and network to deliver financial services such as mobile money transfers, payments, credit scoring and online lending.

However, such commercial transformation is challenging. As a result of surging data use—driven by people’s ever-digitising lifestyles facilitated by Globe, and the pervasive Internet of Things lurking on the horizon—the company has had to invest upwards of a billion dollars a year into its network and IT systems in order to keep up with demand. This has only been made possible through Globe’s service commitments and focused attention to ‘The Transformation House’, where investment into the three pillars is continuous. It now has a workforce that is highly engaged and continues to outperform its counterparts in the industry on sustainable engagement scores. The customers are empowered and are able to access a digital lifestyle enabled by Globe’s services and connectivity.

Today Globe is a market leader, a far cry from its position in 2010. A mere challenger has overtaken the incumbent—something that has never been seen in the telecom industry in the region.

Havovi Joshi

is Head, Communications & Dissemination at the Centre for Management Practice, Singapore Management University

Christopher Dula

is a freelance writer at the Centre for Management Practice, Singapore Management University

Philip Zerrillo

is Executive Director of the Centre for Management Practice, Singapore Management University

1. OTT stands for ‘over-the-top,’ the term used for the delivery of film and TV content via the internet, without requiring users to subscribe to a traditional cable or satellite pay-TV service.