Be prepared for tectonic shifts.

Heralded as the next big economic partnership, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) received a setback when U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew from the pact on his very first day of assuming office. The withdrawal indicated an underlying current of changing global trends, and the American agenda of shifting focus from building trade relations to creating a gateway for foreign investments.

The TPP, a trade agreement between 12 countries that border the Pacific Ocean and represent roughly 40 percent of the world’s economic output, was aimed at lowering non-tariff and tariff barriers to trade among the member nations. A collaboration among five Asian nations, three South American countries, Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada, the objective of the pact was to stimulate economic growth among the participating nations through greater productivity, increased employment and opportunities for innovation.

With the U.S. withdrawal from the trade agreement, it seems unlikely that the agreement can and will continue to operate as planned. Vietnam, for instance, is likely to be negatively affected by the exit of the U.S. from the TPP, but it is noteworthy that, like most of the other TPP member countries, it still has strong bilateral ties with the United States—thus providing the U.S. with greater bargaining power over exports from these countries than might exist in a multilateral agreement.

Trumpanomics

So what happened? The 2016 presidential campaign in the U.S. touted the perception that international trade was a double-edged sword. Though expanded trade had tremendously helped in increasing the supply of goods and services at significantly lower cost to consumers, it had simultaneously affected wages and led to growth in financial inequality. In the U.S., globalisation had contributed to wage stagnation, even though it had brought about a huge surge in productivity over the last few decades. This had led to a brewing dissatisfaction among the working class in the country and fuelled a rise in protectionist attitudes.

Another important point to note is the long term impact of the global financial crisis of 2008 on the world economy in general. Most leading world economies, with the exception of China and India, have experienced sluggish growth after the recession. This has acted as a catalyst for the adoption of various trade restrictive measures to manage rising debt loads and infrastructure challenges, a trend that will likely continue to gain momentum in the coming years.

Reglobalisation

The death of the TPP is an indication of significant changes in trade policies not just in the U.S., but globally. In future, regional trade will be replaced more and more by bilateral trade agreements. For instance, the U.S. will sign agreements not with the European Union (EU), but separately with Germany, France and the United Kingdom. This is also likely to be the case with Japan, Canada and Mexico.

A related global trend that we expect to see is that foreign investments will replace international trade. This is not so much ‘deglobalisation’, but a ‘reglobalisation’ from trade to investment. Interestingly that is how we used to trade before we liberalised and formed the World Trade Organization. But with decreasing restrictions on foreign ownership in many countries, it will make more sense to set up businesses in a country that has a large consumer base—be it the U.S., Mexico, China or India—because one can make in and sell to, and service that market.

Even before Trump’s election, German automobile makers had moved their manufacturing units to the U.S., and corporate giants like Siemens had invested heavily in the country. The German economy is not as big as the American economy, but still relatively big. In addition, German-headquartered multinationals are currently looking at avenues of de-risking from the EU because of the uncertainty there.

I believe the biggest change that is going to happen is the change in the flow of investments from the East to the West. Under this scenario, companies from the East will park their manufacturing units in the U.S. to cater to the demand of both the foreign and home countries. In other words, while many U.S. multinationals have formed Asia Pacific subsidiaries to focus on Asia (often located in Hong Kong or Singapore), Asian companies from Japan, South Korea, China, and ASEAN will now either establish subsidiaries or make acquisitions and focus on the U.S., Canada and the United Kingdom.

Where manufacturing units move, their suppliers follow. European automobile manufacturers, along with their suppliers, are already hubbing in America. And Atlanta is rapidly becoming the Detroit of the 21st century. Eventually, American manufacturers will also shift their capacity to the southern or ‘right to work’ states. These states provide more business-friendly environments to operate in, often providing incentives for investment in manufacturing, labour is relatively cheap, and land is easy to get.

The Korean companies too are moving their manufacturing units to the U.S., much like what Japan did in the 1980s. It is likely that companies such as Samsung will start making phones in the United States. Kia Motors is already in Atlanta, and Honda recently upped its investments to strengthen its North American operations.

The brighter side of Brexit

Contrary to popular belief, I have confidence that the U.K. will come out much better after Brexit. The U.K.’s new (but in many ways, oldest) partner will be the United States. Large British companies such as BAE Systems or British Telecom will now begin to focus on the U.S. and not across the English Channel. The two countries have been politically, militarily and economically aligned since World War II, so that is another reason why there will be a shift from trade to foreign investment. This is also why continental Europeans are not happy with the Brexit decision as they are more adversely impacted by it than Britain. Important to note here is that the U.K. also has access to another big market—the Commonwealth nations. Australia, South Africa, India and Canada are among the larger economies that can offer a lucrative market for British products and services; and there is also an element of familiarity in doing business with these nations.

The EU will certainly be in the doldrums for quite some time, although some smaller nations like the Scandinavian economies will continue to do well. The economies that would suffer the most will be France and Germany, and Italy to some extent; they will be desperate to tap into growth pockets outside their continent. Also, given the monetary controls and the labour mobility issues, there is imminent fear whether the EU will survive. The common currency seems to have further locked in the EU countries, while having an independent currency made it relatively easy for the U.K. to walk away from the EU.

It takes two to tango

We also need to consider the impact of the changing U.S. trade policy on China, Asia’s biggest economy and the second largest economy globally. We will see China investing heavily in the U.S., as it shifts its policy from export trade to more and more investment. Despite the strong anti-Chinese propaganda, the U.S. will continue to allow large local Chinese enterprises to invest in the United States. For example, General Electric sold its appliance business to Haier, a Chinese appliance manufacturing company, and not to Electrolux. These investments are made not only to serve the American market, but also the Chinese market. So Chinese companies will invest and manufacture in the United States in order to export to their home market in China—this is fascinating. We saw a similar pattern in the 1980s when Honda announced that they would manufacture their cars in the U.S. and export them back to Japan. We may also see a spate of mergers and acquisitions, as economies of scale gain more and more importance.

Public debt converted into private equity

As interest rates rise, it places an increasing burden on the fiscal budget. And this is financed through public debt. In the 1980’s, Japan held U.S. treasury bonds. These were used as credit for the Japanese zaibatsu such as Mitsubishi, Mitsui and Sumitomo groups to acquire or build their own manufacturing plants. Japanese firms also bought many assets including consumer electronics, steel, and even portions of islands like Hawaii. When a company gets capital at zero or low interest rates, it finds it easy to invest abroad. And that’s exactly what the Japanese did.

Today, the buyouts will most probably be by China, primarily, and U.S. treasury bonds will be used by Chinese state enterprises to own large corporations in America. This again means that mergers and acquisitions will become large scale very quickly. There will be large-scale acquisitions by Chinese enterprises (especially state-owned enterprises); this will result in globalisation of industries where Chinese enterprises will be major global players/competitors.

We are also likely to see massive infrastructure investments financed through the fiscal budget in the coming years. Current forecasts for infrastructure investments in the U.S. are of the order of US$1 trillion over the next decade, but I feel it may go up to US$3 trillion, or US$300 billion per year. This will require public-private partnerships since the fiscal budget cannot invest so much purely out of tax income. Thus, these partnerships will become yet another important way of converting public debt into private equity.

Singapore’s strategic advantage

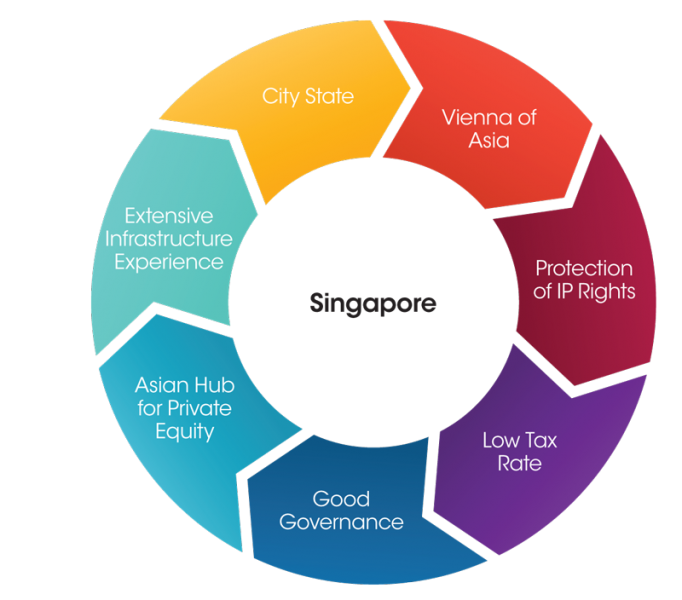

Amidst this scenario, Singapore sits strategically in the right place, ready to capitalize on its competitive advantage in Asia. Singapore has advantages over its peers in that it is a city nation that is fairly neutral. I call Singapore the ‘Vienna of Asia’. Like Vienna during the Cold War, Singapore could potentially become a city to host negotiations and provide a platform for track two diplomacy.

Singapore also has several other advantages including strong intellectual property (IP) rights, low tax rates and good governance. The island state is already the Asian hub for private equity but so far it has been focused on investments in Asia, notably

China, India and the ASEAN countries. As the flow of capital from East to West increases, Singapore has the potential of being the investment gateway for Asian enterprises investing in the U.S., Canada and Mexico. In order to take advantage of these opportunities, Singapore will first need to reposition itself from being a trading capital to an investment gateway looking out to the West.

Strong governance and ease of doing business have also made Singapore an attractive spot for Asian companies to set up regional offices. The city-state is therefore in a strong position to facilitate yet another reverse trend of attracting American investment into Asian conglomerates. Finally, the country has extensive infrastructure experience, from its landfill projects to ports and even botanical gardens. Its expertise in running massive infrastructure projects is well known and emulated throughout the world. So Singapore has the potential to bid for large infrastructure projects in the U.S., leveraging on its expertise.

Asia: The new battleground?

I foresee a change in world geopolitics whereby Asia will become the new economic, political and military battleground. The country (Russia) that has been an enemy in the Cold War with the U.S. for many years will become its friend, and the U.S. will accept this friendship. The U.S. is very likely to move out of West Asia and the Arab countries and shift its attention to Asia. China will replace Japan as America’s major competitor both economically and, of course, militarily.

However, despite its current and potential economic growth, the brittleness of Asia can be seen in the political instability of countries like Thailand and the radical changes taking place in the Philippines. This, coupled with China’s increasing prominence as a global economic and military power, will most likely push Asia towards a global tension point; and experts will be closely watching how the U.S.-China relationship develops.

Change is imminent. The global economic playing field is witnessing a radical shift—what I call a tectonic shift—from being western-centric to Asia-centric. While opportunities exist, it will be interesting to see how changes in the way global business is conducted impact not just economies, but even political and military regimes across the world. No doubt, there will be winners and losers.