Digital technology, including e-commerce and e-market exchanges, has been the most significant disruptive force for the retail industry in the last two decades.

Is our virtual world gaining precedence over our real world? I have seen people rush back home to milk their virtual cow before sunset in an agriculture-simulation social network game, even as their children wait to get their parent’s attention. Across generations, people are so focused on their smartphones, tapping on ‘likes’ of photos of friends having lunch or travelling to school that they often forget to notice, much less speak, to their family and the passengers they share rides with. No doubt, the online world is attractive, captive and yes, even addictive. And it is pervading every aspect of our lives, not just the social.

Nowhere is this online explosion more visible than in the retail industry. In the global retail sector that boasts of an estimated US$26.1 trillion in revenue for 2020,1 representing a third of the world’s GDP and employing millions of people, e-commerce has been growing at 23 percent per annum between 2012 and 2019, and will account for 15 percent of the total retail sector by 2020.2 At this rate, revenue from online retail will surpass US$5 trillion by 2020. Nonetheless, 85 percent of retail revenue today still comes from physical stores. Hypermarkets and supermarkets account for 35 percent of the retail direct sales globally, and these numbers do not account for cash-based informal retailing such as street vendors and small rural shops.

While the growth numbers seem impressive, the retail sector is, in fact, in trouble. In 2018, 5,864 retail stores closed down in the U.S., and another 9,100 were set to close in 2019.3 Among those affected are many iconic brands like H&M, Ralph Lauren and Michael Kors. The U.S. shopping malls are running empty. Even more worrying is the fact that world-class retailers like Toys“R”Us, RadioShack and Sears have filed for bankruptcy. And despite the continuing attraction of the ‘mall culture’ in Asia, retailers in this region are also suffering. International retailers such as Carrefour, GAP and Banana Republic have closed their Singapore storefronts. Local and regional brands such as furniture and home retailer iwannagohome and fashion house Raoul have also downed their shutters over the past few years, with cosmetics retailer Sasa and DIY chain Home-Fix as the most recent casualties.

Why do good retailers go bad?

What we are seeing is reduced footfall in physical stores, making the brick-and-mortar format seemingly unsustainable in the face of online retail. The Wheel of Retailing and the Retail Gravitation theories have been proposed as explanations for this trend. The former states that new types of retailers generally enter the market as low-margin, low-status, low-price operators that would gradually move to more elaborate premises and facilities and get replaced by new low cost competitors. Meanwhile, the Retail Gravitation theory proposes that customers are willing to travel longer distances to larger retail centres given their greater attractiveness to customers. However, in my opinion, most good retailers go bad because they are either unable, or more importantly, unwilling, to adapt when their ecosystem changes rapidly. Many of the bigger, successful companies are fast falling behind their smaller but nimbler online competitors because their legacy systems do not allow them to adapt quickly to changing market conditions.

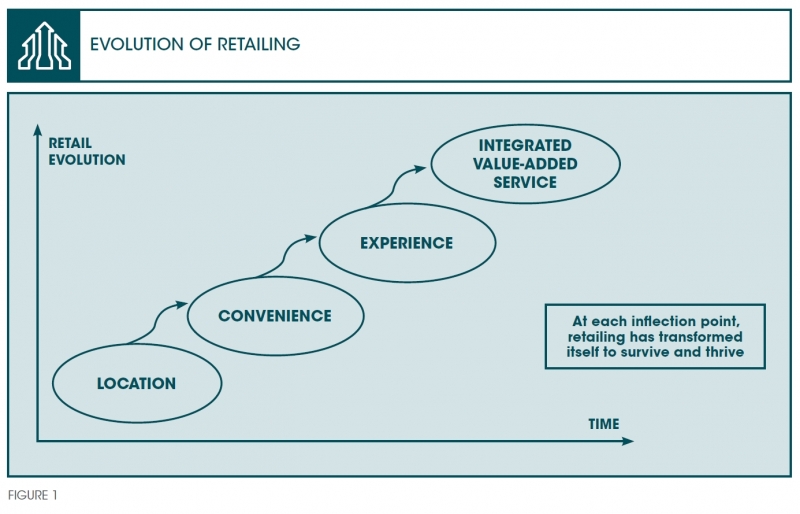

Over the last 150 years, the retail sector has evolved from providing location and convenience to a full customer experience. This is the stage we are at now. Moving forward, the retail industry can and will reposition itself in the face of emerging trends and changing dynamics not only to survive but also thrive in the new environment. It will do so by evolving into a provider of integrated value-added services (refer to Figure 1). Technology will be a key factor driving this future positioning.

Rise of retail brands

One of the most noteworthy trends in retail has been the shift from manufacturing brands to retailing brands. Interestingly, this shift impacts both the online and offline space whereby retailers are creating their own brands using a name that is different from that of the retailer. For instance, each house brand for product categories such as men and women’s clothing and home products sold in Walmart is not branded as ‘Walmart’, but has its own unique brand name and sells exclusively in Walmart stores.

When fast-moving consumer goods manufacturing took off 150 years ago, retailers did not have much market power as merchandise was mostly sold through mom-and-pop shops or small-scale retail chains. Manufacturers wielded market power through product brand loyalty and by controlling the supply chain. Today, the tables have turned as retailers now understand the pulse of their customers, and they use this intimate understanding to offer product solutions or experiences that go beyond the utility, convenience and style of the product. As such, retailers have gained a lot more market power and customer loyalty compared to manufacturing conglomerates like Unilever and Procter & Gamble. Companies like Walmart, Amazon and Alibaba have seen amazing overall growth, and who would have thought that Walmart and Sam’s Club would become the biggest retailers for diamonds in America?

Although the concept of private labels is not new to the retail industry, the difference today is that these brands are of a very high quality as the retailer controls the design and chooses a manufacturer that can deliver on quality, not just on price and volume. In fact, retailers are proactively challenging the mindset that private labels are low-quality alternatives. They are getting smarter by marketing the private labels as the premium products in their stores. These companies take pride in their own brands, which account for a big chunk of their revenue.

Retailer brands have also proved to be lucrative for business. Britain’s Marks & Spencer and America’s A&P (Atlantic & Pacific) were some of the first retailers to manufacture their own products and sell only private labels, and were well known for their quality. The U.S. department store chain Sears was known for its Craftsman tools and lawn mowers and Kraft tools, which competed favourably with leading brands like Black & Decker and Toro. In fact, Sears sold its Craftsman brand to Stanley Black & Decker for roughly $900 million.4 Sears had 18 such brands, including Kenmore, for home appliances. Kenmore washing machines were manufactured by Whirlpool but the Kenmore brand had a higher valuation than that of the appliance manufacturer because of its larger market share.

Costco Wholesale, the leading membership warehouse club and the second largest retailer in the U.S. with annual net sales of US$138 billion, has its own brand named Kirkland that accounts for about over US$39 billion, or 28 percent of its revenue.5 Big Bazaar, the Indian retail chain of hypermarkets, discount department stores and grocery stores, has also been successful with its line of retailing brands. Flipkart in India has a whole range of private brands, none of them labelled Flipkart. And in China, Alibaba is doing the same thing.

Customised pricing in digital retail

Digital retail allows for customised pricing, meaning the price paid by one customer for any particular good or service can be very different from the price paid by another. This is common in the airline industry that operates on a yield management model, where the focus is on optimising the revenue per seat per mile for all flights. For example, say out of a total of 100 seats, the airline manages to sell 80 seats at the regular price. As it does not want the remaining 20 seats to go empty, it offers a price incentive to fill the remaining seats. Hence, it is quite possible that the person sitting in the seat next to me could have paid just 20 percent of the price I paid for the same seat. This could be because they booked well in advance or because they bought the ticket at the last minute, or went through an aggregator that gave a heavy discount. Similarly, the hospitality industry also offers customised pricing through the aggregators.

Unless there is government regulation, price discrimination can be exercised customer by customer. If one shops for clothes online and visits the same websites regularly, the online retailers can know individual customer preferences and offer customised promotions and incentives. This level of customised pricing is much harder to implement in the brick-and-mortar format.

Repositioning of retail

In the digital age, brick-and-mortar retailers need to move away from selling merchandise to offering integrated value-added services. The prominent trend to watch out for is the transition of traditional retailers into the area of service delivery with the help of e-commerce platforms. We are seeing this first and foremost in the online food delivery business. A food business no longer needs to invest in and develop its own delivery services—companies like Amazon in the U.S. are delivering food within two hours, while general retailer Kroger is competing fiercely to cut down its delivery time to one hour. In today’s fast-paced world, customers are more than willing to forego the experience of dining in a restaurant and pay for this service, just to enjoy the convenience of home delivery—this has developed into a market that has been well captured by companies like Uber Eats, Grub Hub, and Dash.

We are even seeing companies using merchandise as a loss leader and make money on financing or other services like maintenance contracts and extended warranties. For Sears, its largest profit was not from the sale of home appliances, but from issuing credit cards and extended warranties against home appliances. In the early 2000s, these revenue streams were largely responsible for keeping the company buoyed in the face of declining store sales.

Best Buy, the multinational consumer electronics retailer, surprised the market by announcing its intention to move into services. In 2002, it bought a company called Geek Squad, whose technicians help to deliver and install the purchased product in the customer’s home, and also service the maintenance contract. The service contracts provide a steady revenue stream for Best Buy. Apple Inc is doing the same with its content streaming services, just as the subscription service Amazon Prime has created a healthy cash flow for the retailer.

Even as shopping malls become more of service malls (making money only from movie theatres and F&B outlets), brick-and-mortar retailers in these properties will metamorphose into omni-channel retailers. They are already positioning themselves to offer a host of options for the customer, from online ordering with store pickup to in-store shopping with home delivery. E-commerce alone cannot provide this kind of convenience.

Equally, online players like Amazon and Alibaba have started investing in physical stores, but they will offer a very different experience to their customers. This is already happening to some extent, and the Apple stores are a very successful example of this. The success of Amazon Go in Seattle is also evidence of the innovativeness and creativity with which online players will enter the physical space. Additionally, as mass merchandise goes online, brick-and-mortar retail stores will become specialty stores.

The latest trend in the U.S. is what I call the ‘uberisation’ of merchandise, where we are finding that 35 percent of all merchandise—from furniture to clothing—is rented. Very similar to leasing in the car industry, these retailers have now become service providers because ownership does not change hands.

When the artificial becomes real

The rise of non-traditional competition and changing consumer lifestyles has certainly played a major role in changing industry dynamics for retailing. However, digital technology, including e-commerce and electronic market exchanges, has been the most significant disruptive force for all industries in the last two decades. The evolution of retailing from being location-centric to convenience-centric, and then to experience-centric, will transform it into a provider of value-added services, enabled by digital technology. Over the coming years, retailing will become more of services retailing, and this will distinguish the winners from the losers.

It doesn’t stop here. In the future, industry change will be further accelerated with the advent of new technologies like artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and blockchain. As the artificial becomes real, retailers will have to adapt and rejuvenate their business models and core practices for survival and growth in the future. We are already seeing glimpses of this change in smart checkouts, robot assistants, and virtual shopping networks, which will become more pervasive over time.

Brick-and-mortar retailing is here to stay, but it will be revitalised and repositioned for the future as it has always done ever since the industrial revolution.

Jagdish Sheth

is the Charles H. Kellstadt Professor of Marketing at the Goizueta Business School of Emory University

References

1. Liam O’Connell, “Global Retail Sales 2017-2023”, Statista.com, November 28, 2019.

2. J. Clement, “Global Retail E-commerce Sales 2014-2023”, Statista.com, August 30, 2019.

3. Hayley Peterson, “More than 9,100 Stores are Closing in 2019 as the Retail Apocalypse Drags on”, Business Insider, November 12, 2019.

4. Paul la Monica, “Sears Sells Craftsman to Stanley Black & Decker”, CNN Business, January 5, 2017.

5. Costco Wholesale, Annual Report 2018.