Following the opening of the Vietnamese economy to foreign direct investment (FDI) in 1986, Vietnam became an exciting, albeit difficult, place to do business in the 1990s. Then came the Asian Economic Crisis in 1997, and investors began pulling out in droves. The next decade was a challenging time for the Vietnamese economy, and it was only in January 2007, after Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), that a second wave of investor interest followed. However, there was a large difference between committed FDI, which reached a high of over US$70 billion in 2008, and disbursed FDI, which fluctuated between US$10-12 billion annually.1

Fast forward to today, Vietnam is embarking on its third wave of foreign investment. Given its increased macroeconomic stability, an emerging consumer class, and changes in Asia’s manufacturing landscape, the country is now better positioned to obtain a fuller extent of committed FDI.

Today, Vietnam is embarking on its third wave of foreign investment.

Vietnam: becoming an attractive investment destination

INTRODUCING MACROECONOMIC STABILITY

The years 2007 to 2011 were marked by high credit growth, which lead to high inflation and rapid devaluation of the Vietnamese Dong (VND). In early 2012, facing the realities of an overheating economy, the government shifted focus from a high growth strategy to one that would bring about macroeconomic stability. A number of monetary and fiscal policies were implemented. In particular, tighter monetary policies reduced credit growth from about 27 percent per annum in 2010, down to 12.5 percent in 2013.2

Correspondingly, gross domestic product (GDP) growth declined to 5.2 percent in 2012 and 5.4 percent in 2013, from a five-year high of 7.6 percent in 2007.3

In turn, inflation has significantly contracted, from 22 percent in 2011 to less than 5 percent in 2014.4 For 2015, the government is projecting GDP to expand by 6.2 percent and analyst estimates expect inflation to remain in the low single digit territory.

With low inflation, the government has been able to cut interest rates by a total of 850 basis points since 2012, and position the VND as the most stable currency in the region, with only a 3 percent devaluation against the USD since February 2012.5 The VND has also appreciated against the Euro and Japanese Yen during this period and won the confidence of foreign investors.

ATTRACTIVE DEMOGRAPHICS

Beyond the government’s focus on economic stability, one cannot ignore Vietnam’s large, young and educated population and expanding middle class as a draw for foreign investment. While other countries in the region—Japan, Singapore, and even China—grapple with the challenges of an ageing population, Vietnam has an enviable demographic structure, with its ratio of independent to dependent people among the healthiest in the region.

Moreover, the country is homogenous—with one common language, a single political party, one predominant religion and a contiguous landmass—which provides for greater socio-political stability. This is in stark contrast to neighbouring countries, such as Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar and even the Philippines, where political and social disorder is more common.

But most of all, it is the rapidly expanding consumer class which attracts investors to this emerging market. For a country with 90 million people, the promise of a strong middle class is alluring. According to Boston Consulting Group, Vietnam’s middle and affluent class is the fastest-growing in Southeast Asia, with expectations that it will nearly triple in size from 12 million in 2012 to 33 million by 2020.6

According to the Boston Consulting Group, Vietnam’s middle and affluent class is the fastest-growing in Southeast Asia, with expectations that it will nearly triple in size from 12 million in 2012 to 33 million by 2020.

CHANGES IN THE MANUFACTURING LANDSCAPE

Given the above factors, it is not sur prising that there is renewed interest from international investors. Moreover, FDI that is now coming into Vietnam is stickier, and the investors are far more sophisticated and committed to doing business for the long haul.

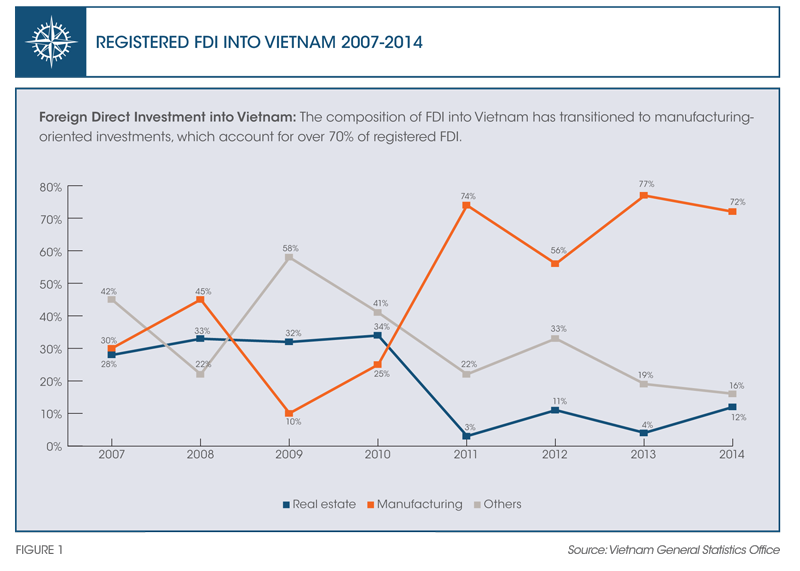

FDI was previously directed towards real estate and other sectors, but is now transitioning back towards manufacturing-oriented investments. As data from the Vietnam General Statistics Office reveal (refer to Figure 1), manufacturing represented only 10 percent of FDI in 2009, but has accounted for 70 percent of registered commitments for the past four years.

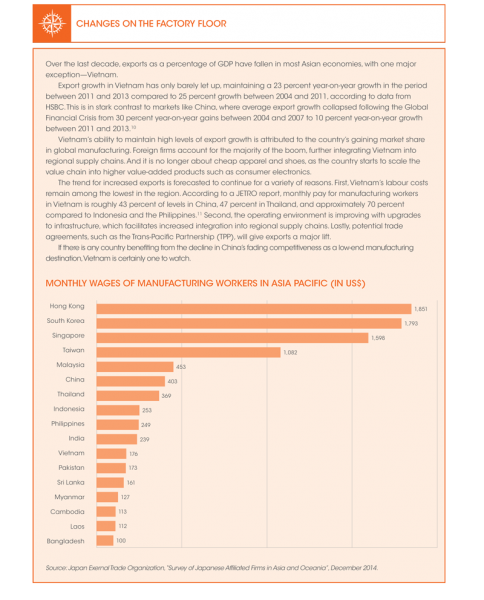

This trend will likely persist as manufacturers migrate out of China into lower-cost destinations like Vietnam.

Total FDI in 2014 amounted to US$20.2 billion. Actual disbursements increased 7.4 percent over the previous year, reaching US$12.4 billion.7 South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan were the primary sources of FDI into Vietnam. South Korea is the largest foreign investor group, driven by hallmark investments from Samsung. Other investors from North Asia have also been highly active in their search to relocate their factories out of China into lower-cost production bases like Vietnam. And while there is a pain point in terms of improving Vietnam’s labour productivity, it has been the experience of multinational corporations (MNCs) that the Vietnamese are quick to learn, and have higher education levels relative to some of their Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) counterparts, with literacy rates higher than 90 percent. As a result, MNCs have been willing to make significant commitments to the country and invest substantially in training their Vietnamese staff.

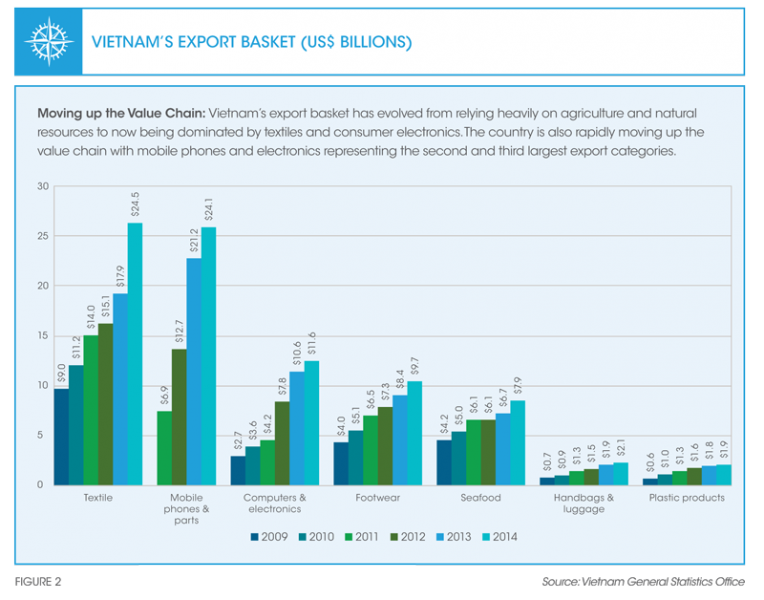

Positive inflow of FDI into export-oriented sectors has led to a 13.6 percent increase in export turnover, reaching US$150 billion in 2014.8 After running a trade deficit for 20 years, Vietnam has generated a nominal surplus for the past three years. In addition to accelerating export values, Vietnam has moved up the export value chain, with smartphones and computer parts becoming the second and third largest export items, respectively, in 2014 (refer to Figure 2). Industry analysts have estimated that Samsung now ships 25 percent of all their smartphones worldwide from Vietnam, with plans to increase this figure to 40 percent in the next 12 months.9 Intel’s largest chip plant in the world is located just outside of Ho Chi Minh City.

Investor trends in public securities and M&As

THE VIETNAMESE STOCK MARKET

There is definitely far more interest in the Vietnam stock market in 2014 as compared to years past. This can be attributed to a combination of renewed interest from local investors, whose traditional investments in gold and bank deposits have been less attractive, and sustained interest from foreign investors, with 2014 marking the ninth consecutive year of foreign net inflows.

According to our analysis, the Vietnamese stock market was the second best performing in Asia in 2014, with 26 percent gains in terms of total returns. Despite the gains, Vietnam still has one of the cheapest valuations in the region with a trailing 2014 price-earnings (PE) ratio of 12.5x and the highest dividend yield. The story is even more compelling beyond the blue chips, as one-third of listed companies have PEs of 6.0 to 9.0x and dividends in the high single digits. International investors have taken notice as 2014 marked the ninth consecutive year of net foreign inflows into the Vietnamese stock market. It must also be remembered that while the Asia-based investor will generally always be more comfortable with Vietnam than a western one—for whom this is often perceived to be a far more exotic frontier market—western investors who have taken the plunge are proving to be savvy, and their investments in the Vietnam stock market have performed well.

DEAL VOLUMES–YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW

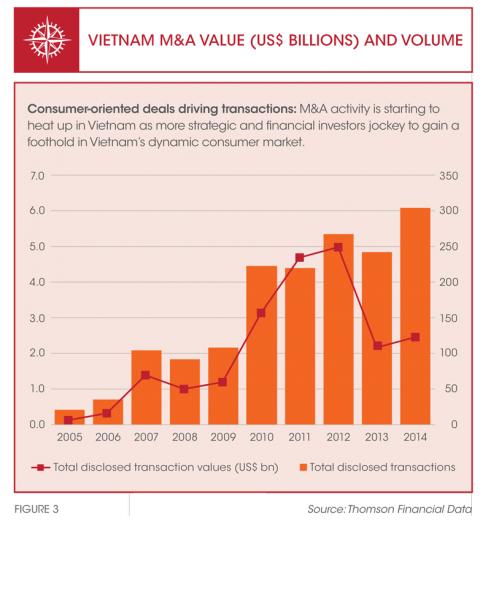

Vietnam has also witnessed an uptick in M& A transactions. According to Thomson Financial Data, there was a 14.3 percent increase year-on-year in M& A transactions in 2014, and total deal volume reached 313 transactions, amounting to US$2.5 billion (refer to Figure 3). Consumer-oriented deals led the pack with investments into retail platforms and consumer goods companies representing 36 percent and 21 percent of deal flow, respectively.

Some of the headline consumer-oriented deals in 2014 included Mondelez International’s US$370 million investment to acquire 80 percent of Kinh Do’s snacks business, the Central Group from Thailand’s US$98 million purchase of 49 percent of the Nguyen Kim group, and Standard Chartered Private Equity’s US$35 million investment to acquire an undisclosed stake in Golden Gate, a local restaurant group.12 And the largest deal of 2014 was Berli Jucker’s US$876 million bid to buy out Metro Vietnam, though it is currently being challenged by the Thailand company’s shareholders.13

GOVERNMENT LOOKING TO EXIT PRIVATE SECTOR

One of the primary drivers behind future deal f low will be the government’s mandate to liquidate a number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The process of privatising SOEs is referred to locally as ‘equitization’ and started in earnest ten years ago. The path to equitization gummed up following the collapse of the stock market in 2008, as valuations soured.

With more buoyant market conditions, the government has come back to the table, equitizing 150 companies in 2014.14 However, demand from international investors has been fairly muted, even for trophy assets such as Vietnam Airlines— for whom the government sold only 3.5 percent in an IPO process, and only to local investors.15

We believe the government overestimates international investors’ willingness to buy shares as soon as they list. And while the government is moving in the right direction, the reality is that foreign investors will not betray basic fundamentals—earnings, management and valuations—and will remain on the sidelines until market-based valuations prevail.

Looking ahead

THE IMPACT OF THE TPP

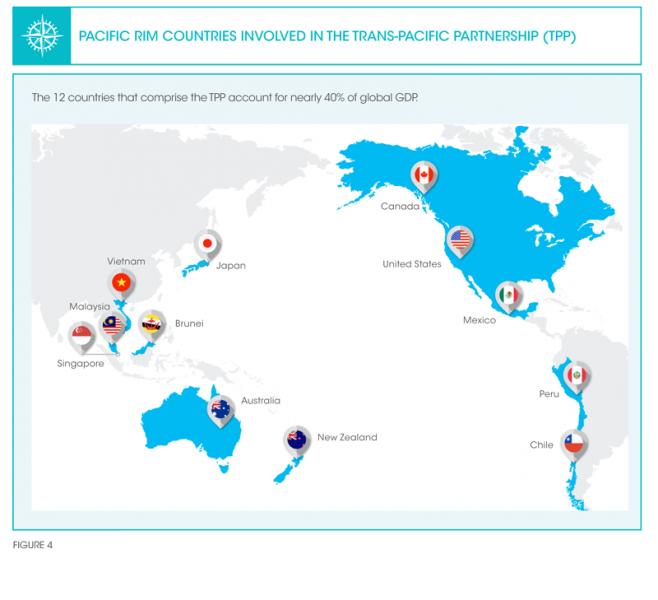

In 2010, Vietnam became an official negotiating partner in the free trade agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The crafting of the TPP between the U.S., Vietnam, and ten other countries across the Asia Pacific region is expected to bring together these economies into a single trading community that would represent approximately 40 percent of global GDP (refer to Figure 4). Once completed, the TPP should lower barriers to trade and investment and increase exports.

The TPP is anticipated to be a major game changer for Vietnam—far more than the formation of the Asian Economic Community—as it has the potential to reshape the light manufacturing industry, particularly in apparel. Vietnam is the third largest emerging market apparel supplier after China and Bangladesh. According to a report from Standard Chartered, with over US$30.6 billion in shipments, Vietnam is the largest ASEAN exporter to the U.S.16 The trade agreement should further increase this number as it would give Vietnam preferential access to the U.S., the single largest consumer of apparel globally (23 percent of imports worldwide). Vietnam’s market share of global apparel exports would prospectively jump to 11 percent.

In 2012, Vietnam exported almost US$7 billion worth of apparel to the U.S., which accounted for 34 percent of U.S. apparel imports.17 Once the TPP comes into play, it would enable Vietnam to export apparel to the U.S. at a zero tariff rate, which would make Vietnamese exports even more competitive. The trade alliance will also bring Vietnam and the U.S. closer politically, as Vietnam pivots away from China towards the U.S., which in turn is looking to counterbalance China’s growing regional presence. In this sense, the TPP is far more than just an economic trade alliance for the U.S. and member states in the Pacific region.

The TPP is far more than just an economic trade alliance for the U.S. and member states in the Pacific region.

The future is not without its challenges

Vietnam’s near-term prospects appear solid against the backdrop of macroeconomic stability, strengthening external accounts and sustained interest from foreign investors. The challenge for the country will be for Vietnam’s policymakers to make the right decisions that will sustain growth in the medium-to-long term.

A July 2014 World Bank report stated that Vietnam faces several challenges on competitiveness that can be addressed through structural reforms, namely equitization of SOEs, recapitalisation and consolidation of the banking sector, and improvements in labour productivity. While the country’s GDP growth has been recovering steadily since the Global Financial Crisis, Vietnam is still performing below potential due to slow progress on cleaning up non-performing loans in the banking sector and removing barriers to private investment by reforming overleveraged SOEs.

However, the overall view is that Vietnam is heading into several good years. The macroeconomic picture is better than it has ever been. There is a young and optimistic population with a real ‘can-do’ attitude. Trade agreements such as the TPP provide the potential to further accelerate exports. And the growth of private domestic players provides for enhanced liquidity and more attractive investments in both the public and private markets.

In 2016, Vietnam will be entering an election year of sorts, where the country’s national assembly will identify the leadership for the next party congress. Despite the upcoming changes at the top, the government is in a prime position to remain steadfast with reforms—the country’s monetary policy has kept inflation low, foreign reserves have been rebuilt due to a strengthening current account, and GDP growth is steadily expanding. The general consensus is that Vietnam is heading in the right direction.

The emergence of a buoyant consumer class and the shifting landscape in Asia’s manufacturing industry make the country an attractive investment destination. Vietnam is at the dawn of a private sector renaissance. As it gets serious about SOE reform, and should be at the top of every investor’s list of high growth emerging markets.