Building scale and volume rapidly is key to surviving the roller-coaster journey and staying the course for a digital entrepreneur.

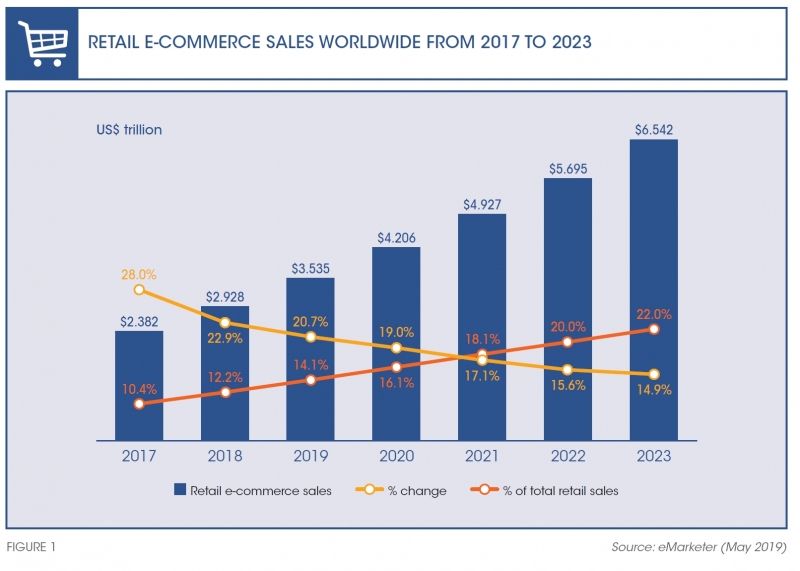

Industry pundits have long prophesised that the days of brick-and-mortar retail will soon be over, and e-commerce will triumph. However, the truth is that physical retail sales continue to outstrip online sales by a huge margin—global retail e-commerce sales accounted for 14 percent of total retail sales as at May 2019 (refer to Figure 1).

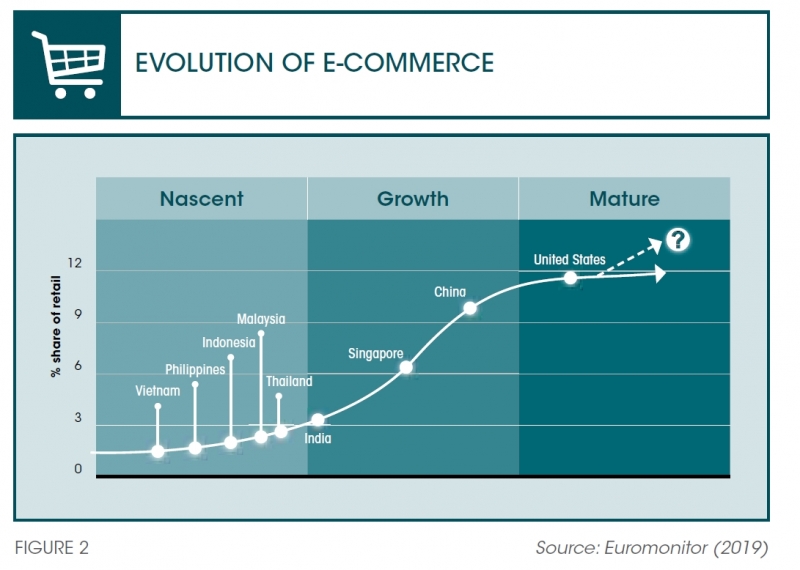

Why is this so? We come across some blind spots when we look at the potential of the e-commerce market. Let’s take the example of Singapore. No doubt, the country has one of the highest digital penetration rates globally. Singaporeans are very comfortable with online shopping, and e-commerce sites like Taobao, Amazon and Qoo10 have become household names locally. In terms of maturity, however, Singapore is still a growing market with e-commerce accounting for only about six percent of its total retail sector (refer to Figure 2).

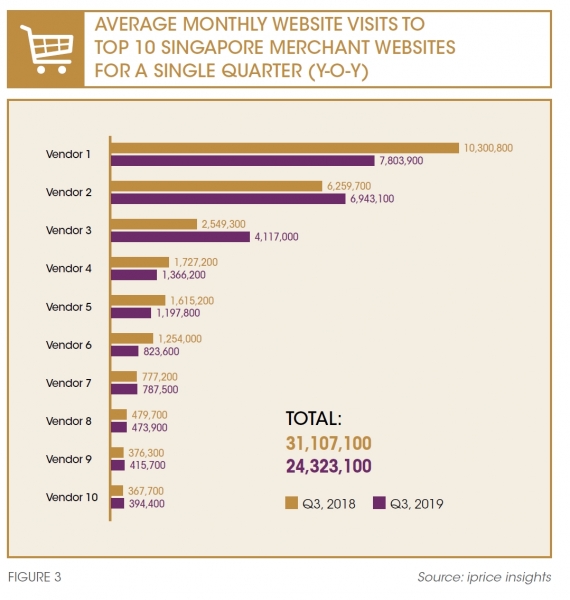

However, when we look at the digital footfall in Singapore over the last three years, we do not see many new users. Even the popular websites don’t register a growth in user visits (refer to Figure 3). The rate might actually be declining. Despite varied efforts by industry players, the e-commerce sector has not been able to acquire genuine new users; any reported increases might be due to fraudulent accounts (or from users who create multiple accounts in an effort to milk benefits from various platforms). Thus, an e-commerce player in an already highly competitive environment would have to worry not just about top-line figures, but also its viability and sustainability moving forward.

The challenge for the digital industry is that no competitive edge lasts long as the information or knowledge one owns becomes outdated very quickly. Two key factors contribute to this. One, the competition is quick to match or improve upon any innovation in the industry. Time-to-market is short, the target market is often within reach and the market reaction is swift. Two, the digital economy has low entry barriers that offers almost no protection to existing players. Emulation is easy, almost anyone can do it, and mistakes are easy to fix.

For a digital entrepreneur, while the take-off may be easy, the challenge is in surviving the roller-coaster journey and staying the course. And to do that, I believe, building scale and volume rapidly is key.

Scale and volume

Digital start-ups need to keep in mind two important considerations. First, while the conventional wisdom regarding scaling up and building volume is to ‘take your time and not be in a hurry’, in the digital world, time is an ill-affordable luxury. The longer a business takes to create scale and volume, the more intense the competition becomes. Take the case of Grab, the Southeast Asian ride-hailing company. It managed to dominate the Singapore market in just three to four years, before any new player could enter the space. Now, with adequate scale and volume under its belt, even with Gojek (the Indonesian company that uses a similar app-driven model) expanding its operations to Singapore, Grab need not worry. In the digital world, the number one player in a market tends to be far ahead of the number two or number three player, unlike traditional businesses where market leaders such as Unilever and Procter & Gamble, or Coca Cola and Pepsi, are often found in neck-and-neck competition with each other. In the online domain, the gap between the leader and the followers is huge. For example, while Google is the number one search engine, nobody even knows who the number two player is. Similarly, Amazon’s online sales in the U.S. are not only the highest in the country, but are also more than the online sales of the next 49 retailers put together.1

Second, a successful business model needs both scale and volume for transactions to take place among its stakeholders. In Grab’s case, the start-up first identified its drivers and riders, akin to sellers and buyers in e-retail, who were its most important stakeholders. Next, it realised that having one without the other—only scale (many drivers but not enough riders) or only volume (many riders but not enough drivers)—would simply cause the business to collapse in no time. In order to create sustainable value, a business needs both.

Given the critical role of scale and volume, the concern for a digital business is how to build them quickly. How can it develop the strategic thinking and the unique mindset required to generate competitive solutions along with maintaining a dynamic pace? I advise companies to adopt the following techniques—the A-B model and multi-point forward engineering—in order to develop built-in competition systems, generate new ideas, reinforce success and evaluate failures in the shortest time possible.

THE A-B MODEL

The A-B model creates a test bed for new ideas. It prescribes having two teams, Team A and Team B, that work on the same project, but independently and without any knowledge of what the other team is doing. They should also not report to the same person. The advantage this method offers is that the two teams are able to break away from the rigidities of structure, and come up with original, out-of-the-box solutions.

At Qoo10, we often have two marketing teams working on developing a promotional campaign for upcoming site-level events or planning Facebook marketing campaigns. The teams are given separate budgets and complete autonomy to decide how they want to promote the event. While both can be telling the same story to engage customers, somehow one team will end up being more effective than the other. Eventually, as the teams are judged purely on their performance, it helps to breed healthy competition at the workplace and create an innovation-led environment.

The A-B approach not only helps to generate excellent ideas, but also perpetuates self-learning and relearning among employees and the organisation as a whole. Most importantly, it keeps the pace of learning and evolving fast. Say, we decide to put a Nintendo switch in Facebook and get a lot of clicks. However, along with the whole world, our competition has also seen it within a short time. And as they quickly emulate or even better our campaign, we need to be ready to move on to another idea. With the swift pace of change, the A-B model serves a critical purpose in the organisation.

MULTI-POINT FORWARD ENGINEERING

The multi-point forward engineering approach prescribes coming up with 10 different solutions that can be simultaneously launched at a given time. To illustrate, imagine 10 people stranded in the middle of an uncharted desert without a map or any directional tools. With no water, no food, and a temperature of 50 degrees Celsius, they are not expected to survive more than three days. What should they do? Should they all go together in a linear path when the probability of finding help is negligible, or should they go in 10 different directions, hoping that at least one will meet with success? Clearly, the latter will be the right choice.

In the business context, when planning to market on Facebook, would a company be able to connect with all its potential users on the social media platform? No, because this depends on how often users check their Facebook accounts, and they don’t do it every minute or even every day. Hence, while Facebook would spend the campaign dollars as requested, there are many gaps in the demographic that would never be captured. Thus, a multi-point strategy is recommended, which advocates opening up multiple future solutions or businesses that a company can offer or enter into at the same time. For instance, at Qoo10, we often push different things simultaneously, such as launching a blockchain platform called QuuBe, a live-streaming function in our Live10 APP, etc. With each new product or service, we seek to reinforce and enhance Qoo10’s overall shopping experience and business model.

However, out of 10 ideas, nine are expected to fail as the competition emulates fast, and consumers are quick to move on. But in the digital journey, failure is something that one can manage and control as online users tend to have short-term memory. Thus, the focus of an e-commerce firm should not be on having a perfect product for the launch. Nobody can do that; even Microsoft Windows and Apple iPhones have flaws. Instead, the company should go ahead and launch the product, listen to market feedback, and patch or improve it accordingly. The response and feedback after the launch is very useful to evaluate the product and determine its relevance and potential. If you launch a lousy product, and receive a lot of complaints, the product has still served its purpose as you get to learn directly from consumers what should be improved.

Focus on business fundamentals

For a digital start-up with limited resources, laser-sharp focus is needed on business fundamentals. The company needs to question whether its efforts will lead to an increase in buyers or sellers, or whether it should skip the ‘wish list’ until it is successful. An example of such a choice could be selecting the background colour of a company’s home page. The answer to this is simple. Why not just change it? Instead of commissioning consultancies to conduct market research and use up resources to find out user preferences, it may be more prudent to go ahead and just make the change. If it looks unsuitable, there is always the undo button to revert to the previous background colour. Does that impact our business? Maybe in the short-term, but remember, online consumers tend to have short memory.

This lack of fear of rejection or failure in the e-commerce domain is what makes the multi-point strategy effective. It is best that a start-up does something rather than nothing at all, even though in all likelihood, 90 percent of the new products/features/ideas will fail, and the 10 percent that succeed will have a limited ‘successful’ shelf life. The ideas that fail or become outdated can be reworked and relaunched again as the next version, and they may work this time, or they still may not—but there is only one way to find out, and that is by trying.

However, none of the approaches would work if the market is not ready to adopt the products offered. And no matter how good its idea may be, a start-up can’t wait for the market to mature on its own, because its competitors or technology will soon seal its fate by imitating or doing it better. Hence, the company has to push and/or cajole the consumers into buying, through adoption of some of the following strategies.

PRICE DISCOVERY (VERSUS CONTENT DISCOVERY)

Price discovery or deep discounts through promo codes is one of the most popular tactics used to enforce market readiness. For instance, ride-hailing apps like Grab and Uber offer scores of promo codes for riders and a host of incentives to drivers to drive product adoption and gather speed in building scale and volume in a new market.

In an immature market, price discovery aids by pushing consumers to do what they otherwise would not. Discounts help to overcome their unwillingness, lack of trust, or other habitual barriers, such that shoppers buy online even when they would have preferred to buy from physical stores, or travellers use a ride-hailing app even when they would have rather flagged down a taxi.

Price discovery is especially effective in Asia as shoppers here have a thrift mentality, and are actively on the lookout for the best deals. In addition, Singapore shoppers have a fear of losing out, a phenomenon termed kiasu. A promotion or a best-seller list, or even simply a ‘deals’ or ‘weekly specials’ tab on the website home page, can generate a high level of excitement, prompting shoppers to buy what everyone else has been buying. In this respect, their behaviour pattern in the offline and online space mirrors each other. The difference between the two is in their reach and speed of consumer response. A promotional banner outside a physical retail shop will at best be seen by shoppers who pass the shopfront, and possibly reach out to a few more through word of mouth. However, in online retail, such news goes viral in real time. With mobile push notification, the whole target market can be accessed in a jiffy, and soon the product could become a best-selling item.

Since online retail is fast-paced from the very beginning—with super-quick consumer reaction times—businesses need to deploy price discovery in the early stages of their operations. Securing the scale and volume in the shortest timeframe will be akin to a proof of concept, and this would indicate the business’ readiness to go to the next level: Investors, here we come! Speed in achieving scale and volume is also important, hence businesses must seek to not just be the first mover, but also the biggest and fastest mover. With a massive user base or a large ecosystem, size will help to insulate the business against external shocks, and thereafter efforts can be channelled towards sustainability and profitability.

DIGITAL RING-FENCING

As a digital player, it is important to be ready for and welcoming of all digital marketplaces, whether local or international. The branding or the user interface, while important, is secondary to footfall allocation. When Amazon with all its might could not enter China directly, it decided to do so through Pinduoduo, the country’s new but increasingly popular e-commerce platform.

Moreover, digital marketplaces not only attract the most visits of all the e-platforms, they also tend to have very low barriers to entry. An online company can enter, register and upload its products at almost zero cost. Digital ring-fencing is thus an easy, low cost and quick method for an online brand to be present on multiple platforms that consumers visit. This increases manifold the opportunities for brand-customer interactions, resulting in high consumer awareness and recall, which are stepping stones for building brand equity.

On the other hand, it is also important to be cautious as marketplace brands tend to become self-fulfilling traps. For example, while Alibaba’s T-mall and Taobao marketplaces generate considerable sales, especially during mega promotional events like Singles’ Day, they can lead to an adverse spillover effect. With a single day accounting for more than six months of a company’s annual revenue, there is tremendous pressure on it to do well in such events. Since consumers specifically look for special deals during these events, the company is compelled to continue offering similar or higher discounts in order to increase its sales. And when its sales volume increases, it has to sell even more goods at discounted prices, thus digging its own grave.

GETTING THE E-MIX RIGHT

It is important for an online business to select the most suitable and relevant keywords, so that the advertisements of its products or its website pop up when shoppers search for the particular category on Google or any other search engine. The right keywords enable the company to be seen by the ‘real’ shoppers—those who are looking to buy that product, and are not just general browsers.

In addition, online companies need to enhance customer value by using impactful and creative product images. Each stock-keeping unit should have multiple images (seven to eight) capable of conveying meaningful information quickly, such as country of origin, branding, benefits, differences from other brands, pricing and product size.

Testing resilience

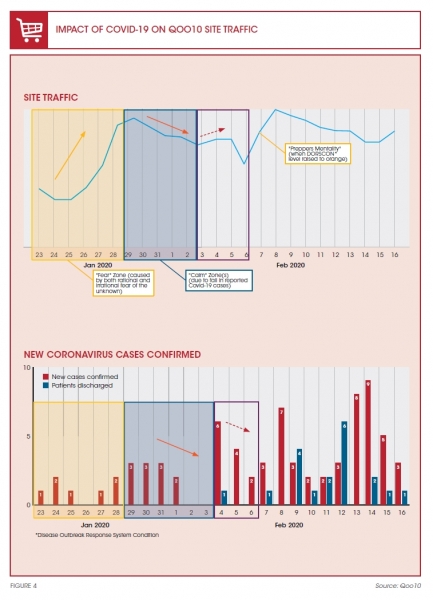

Time and tide wait for no one. While preparedness is key, the true test of resilience takes place when markets are in disarray and demand a real-time response. The Asian e-commerce retail market has recently gone through a stress test with the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus. Using data on site traffic for Qoo10’s online retail platform, we can map consumer behaviour patterns and see how shopping behaviour changed in response to the news about the spread of the virus, and its impact on e-commerce supply chains (refer to Figure 4).

During the week when the first few cases of the virus were discovered in Singapore, Qoo10 witnessed a sudden, sharp spike in site traffic. We can refer to this phase as the ‘fear zone’, which was driven by shoppers’ fear of the unknown. The week started with a surge in demand for surgical masks, and from there, it expanded to searches for disinfectants, hand sanitisers, and other preventive products. In the following week, site traffic experienced ebbs and flows based on the number of confirmed new cases reported in the island-state, interspersed with the ‘calm zone’ on days when there were no new cases, or when the number of new cases was lower than previous days. Anomalies were spotted in week three. Although the number of reported new cases was on the downtrend, traffic to the Qoo10 website witnessed another sharp spike and an increase in sales for non-Covid-19 items like diapers, infant formula, rice, toilet paper, and other household essentials, signalling panic buying. We refer to this as the ‘Preppers Mentality’. The real trigger came a few days later when the Singapore government notched up the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition level from yellow to orange, signalling the heightened severity of the situation. The ‘Preppers’ Mentality’, together with the ‘Kiasu Mentality’, propelled the site traffic to an all-time high.

FACE OFF: CAN MARKETS COPE?

E-marketplaces like Qoo10 are open market platforms for buyers and sellers. The escrow function held by the platform owner is one of the key tenets that builds trust and enables transactions to take place. It operates akin to the economic concept of perfect competition, or an open market model where trade can exist without any barriers of entry, with perfect information, and is driven predominantly by the principles of supply and demand. Prices are determined through fair and open competition. However, in reality, a global-level event like Covid-19 exposes the limitations of e-marketplaces, like that of any open market model.

When pessimism overcomes rationality, the resultant sudden demand spikes can overwhelm and short-circuit the supply and logistics. Markets, both online and offline, cannot keep up with demand. In the online world, such market distortions are exacerbated and amplified by time (or rather the lack of it). Such market distortions can often lead to short-term profiteering and increased levels of potential fraud/scams.

Subsequently, the question arises: Could e-commerce markets have predicted the demand spikes and panic buying experienced during these few weeks? For many, they may think that this would be possible with artificial intelligence (AI), but to put things into perspective, the last major global event of such a scale—SARS in 2003—pre-dates e-commerce and AI. Without pre-existing datasets, AI would be limited in its usefulness.

E-marketplace 2.0: Upsizing supply robustness

With cross-border e-commerce taking shape globally, there is a greater call for a mega e-marketplace, one that is even bigger than China-centric Alibaba’s platforms. Amazon, despite its size, technological prowess and logistical efficiency, also faced an uphill task in handling a global event like Covid-19. When demand spikes 10 times over, the choke points will not be its logistics efficiency in terms of delivery, but actual physical stocks and replenishment of supplies.

Now imagine a powerhouse mother-of-all e-marketplace platform that houses every eminent player from global giants like Alibaba, Amazon, Rakuten and Gmarket to domestic behemoths like Qoo10, Tokopedia and others. In short, global demand meets global supply in a single online marketplace. While the concept of borderless e-commerce trade is attractive, today it is still bound by exchange rates and currencies. To tackle this, we might see the emergence of a unified global digital currency—much like Facebook’s Libra. There are already workable technologies like blockchain that can be used to build it. Just as technology can enable a single global online trade platform, solutions are being refined even as we speak to offer a seamless global payments system eventually. The future is here, and it is time to act.

Sam Too

is the Division Leader (General Manager) of Qoo10 Pte. Ltd., Singapore

Reference

1. 1 Arthur Zaczkiewicz, “Amazon, Wal-Mart and Apple Top List of Biggest E-commerce Retailers”, WWD, April 7, 2017.