Looking at the current state of the global economy and the extent of financial market hedonism through the lens of Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray”.

The Picture of Dorian Gray, a novel by Oscar Wilde,1 is a perfect analogical device that can be used to demonstrate the effect of the hedonistic policies of corporations, bankers, central bankers, regulators, and governments, which focus only on the strength and vibrancy of the financial markets, but discount their resultant debilitating impact on our core economy, industry, and society.

In his philosophical novel, Wilde narrates the story of Dorian, the young and handsome subject of a portrait, who comes under the hedonistic influence of Lord Henry and pledges his soul in a trade under which the painting will bear the burden of his age and deeds. As the story progresses, Dorian indulges in every pleasure that life can provide and commits several sins, including murder. He then attempts to destroy the painting, which depicts his true dark persona, and ends up killing himself. After his death, the painting is restored to its former beauty.

Dorian’s story presents us with a vivid correlation to the current state of the global economy and financial markets. Like Dorian’s beautiful portrait, which is not a true depiction of the subject, the financial market ostensibly reflects a healthy image of the global economy when, in fact, it is weak and withering from within. Dorian’s pursuit of a deeply hedonistic lifestyle is reflective of the financial market as it stands today, with its unrealistic efforts to reflect a perennial growth trajectory. The forced Back to Business as Usual (B2BAU) approach of the market, even when its health is unable to sustain the pressure, has created a mirage that is at great odds with the real economy.

Is Dorian’s tragic death after a pursuit of hedonism possibly a future that can be avoided by the financial world? This article explores this question through the lens of Dorian’s story, and tackles the issues of shareholder maximisation and the B2BAU-oriented slippery slope of politico-economic governance, while also highlighting the urgency of course correction.

The origins of the financial market 'persona’

The global economic model transitioned from feudalism to capitalism during the 17th century, when merchants and traders who traditionally made money from trade started to invest in new productive and machine-led businesses, and derive wealth from the ownership and control of the means of production. At the same time, the regulatory umbrella of their respective royal governments sheltered these mercantile corporations, while their quest for colonial expansion further fuelled capitalistic growth.

With the passing of the Joint Stock Companies Act (1844) and the Limited Liability Act (1855) in the U.K., the rise of capitalism gave a unique identity and character to the ‘market’.2 At the core of this market ‘persona’ was the economy of the rich European nations, which established the eminence of the concept of economic surplus. The deployment of this surplus led to the creation of more jobs and the production of more things with the latest innovative technologies, thereby improving people’s lives.3 With the smooth and free movement of capital and goods across borders, the world started to capture the benefits of trade, commerce, and capitalism. By the middle of the 20th century, the financial market was well-established (just like the completed portrait of Dorian) and it reflected a solid and robust form of the global economy. Today, it is common to monitor and analyse the behaviour of the ‘market’ as though it had a personality of its own.

Market hedonism and its principles

Market hedonism in the context of a capitalistic environment is the belief that maximising the performance of the financial markets is the primary reason for their existence. The fundamental belief is that tomorrow will be better than yesterday, and if this is not so, then the day after tomorrow will definitely be better! Capitalism transitioned from the mercantile (gold and commodity-based) system to one that is currency and derivative-based, which was built on the philosophy of credit and trust. It further incorporated the concept of the quintessential ‘un-violable’ financial trust in the government, hence this gave governments an almost unlimited ability to borrow.

Furthermore, the market was seen as forever dynamic, growth-oriented and profit-generating. It was deemed capable of intelligently valuing the future earnings of a firm on an analytical basis. The capital market with its globally, publicly- traded businesses operated on the basis of the core belief that financial performance, as measured by profit, whether current or potential profit over the long term, was the measure of financial success.4 In fact, Milton Friedman in his seminal 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom reiterated the view that maximising profit was a ‘social responsibility’ of the corporation.

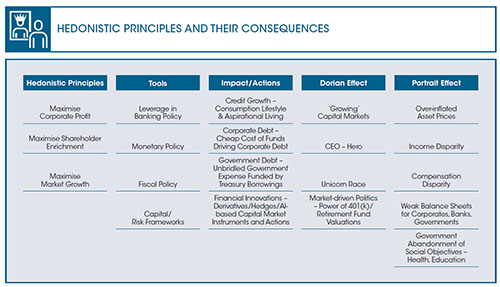

The tools of the market hedonist and their impact

Over the years, the hedonistic beliefs and principles reflected in organisational presentations and pitchbooks have been driven by the core tenets of leverage and growth through monetary and fiscal policy, and these have been further supported by the cognitive and moral impropriety of policymakers.

LEVERAGE

The market, under the influence of bankers, economists and regulators, thrived on the core principle of the depreciating value of money, which has enthused global consumers to enjoy a hedonistic view of life, seeking pleasure by buying everything they desire ‘now’ on credit.5 A large part of the developed world today has household debt well above 50 percent of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The American dream of a big house and a driveway full of cars has spread beyond the shores of the U.S., and there are many other countries like Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, and Canada where the household debt is over 100 percent of GDP.6 Asia-Pacific economies are not very different. Australia and South Korea belong to the same club. Real estate prices built up during the early part of this century led to excessive borrowing among households globally, which ultimately led to the 2008 global financial crisis.

The debt phenomenon extends beyond individuals to businesses, where the global corporate and government debt has increased from US$87 trillion in 2009 to over US$115 trillion in 2019.7 Private corporates have been borrowing heavily, especially across the developing world. Corporate debt in China for instance reached 166 percent of GDP in 2018, while the country’s total debt to GDP increased by almost 80 points from 2010 to reach a staggering 257 percent in 2018.

MONETARY POLICY

The consequence of the global financial crisis was the immediate collapse of the market—the U.S. stock market crashed from a high of 14,000 in November 2007 to just below 7,000 by February 2009. The financial economy needed strong intervention to first protect, and then resurrect the market to its past glory. Monetary policy stimulus across multiple economies was thus used as a blunt instrument to support the market. The central banks across the globe acted not only to dramatically reduce interest rates, but also used unconventional instruments like Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) to arrest the decline of the markets.8 Research reveals that quantitative easing (QE) programmes launched by the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Union did manage to have some positive effect on the core economy, and the QE2 is believed to have reduced the unemployment rate in the U.S. by 0.3 percent.9 However, the real objective was to transmogrify the market, which then magically recovered to the September 2008 pre-crash levels by April 2010, such that the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) hit 11,000, thus quickly erasing memories of the lows of February 2009.

At this stage, rather than look at the severe hits that the real economy across the world had taken, the financial world quickly went on to enjoy the public image of market glory. The aggressive monetary policy steps involving excess liquidity, the exceptionally low interest rates, and the LSAPs were sustained for inordinately long periods across Japan, Europe, China, emerging markets, and even the United States. Theoretically, the central banks could have unwound the excessive interventions like the LSAPs. They however failed to do so, reflecting either their intellectual weakness or their lack of moral courage to address the underlying painful issues. The hedonistic pressures of capitalism thus forced them to revert to B2BAU, resulting in the market quickly returning to its self-indulging ways, to achieve new highs almost every year.

The market along the way had also invented new hedonistic values. CEOs were proclaimed as heroes who drove multi-billion dollar corporations to gain trillion-dollar valuations. Venture capitalists and investment bankers/ wealth fund managers meanwhile were fuelling the unbridled desire towards obtaining unicorn status. As for ordinary people, they were enjoying the gratification from the ballooning 401(k) and other retirement fund valuations. And amongst all this, the market was back to its shining and roaring best, culminating in DJIA’s peak of 29,551 in February 2020. The Dorian effect was at its apogee once again.

FISCAL POLICY

The recent Covid-19 pandemic is yet another example of an external shock that is expected to have a serious long-term impact on the global economy. As the debilitating effect of the virus rampaged across the globe, the market took a huge tumble globally. The DJIA fell from 29,551 on February 22, 2020 to 18,591 on March 23, 2020, and gave up 37 percent of its peak valuation. For a moment, there seemed to be no bottom in sight for the market. The global political and financial leadership intervened with the tried-and-tested monetary policy intervention to provide solidity and stability to the market. However, the underlying malaise was clearly more powerful than the medicine, and the market was unable to recapture its past beauty. Undeterred, the heroes of capitalistic philosophy unleashed their next weapon—fiscal stimulus. Across the world, nations announced trillions of dollars’ worth of fiscal spending, with most large regional economies like the U.S., Europe, and Asia pumping in over 10 percent of GDP for this.

The underlying economy, however, seems to have become so weak that small businesses and factories across the world are shutting down at a rapid pace, causing unimaginable levels of unemployment and income destruction. As the real economic impact of the virus pans out over the next several years, the fiscal stimulus will struggle to provide strength to the underlying economy. Each revision of estimate of economic output for the global economy is likely to become more negative than the previous one.

CAPITAL/RISK FRAMEWORKS AND RELATED POLICIES

There is already talk that to provide any sort of sustainable strength to the market (this remains the core tenet of market hedonists even now), and with a commitment to do whatever it takes, the fiscal stimulus would need to be multiplied in strength. In addition, the financial and corporate world may need further support for the global capital and risk frameworks. Banks are being asked to defer loan payment schedules for individuals and businesses, and there is talk of relooking at capital requirements for financial institutions. This is because non-performing loans will build up as the crisis deepens. There is also talk in the U.S. about the issuance of a 30-year or 50-year trillion-dollar Covid-19 bond. This is, once again, a B2BAU approach, where we are regressing to the philosophy of kicking the can down the road for future generations to pick up and pay the bill for us.

The portrait (economic fundamentals) effect

The effect of the profligate credit, fiscal, and monetary policies over the last few decades is that the social objectives and responsibilities of political governance have been compromised. There has been a huge increase in personal debt.10 Wealth inequality has widened, with the wealth of the poorest half across the world falling by a trillion dollars since 2010, and the wealth of the top 62 people in the world increasing by half a trillion dollars during this period.11 The income and compensation disparity between employees and CEOs has also worsened, with CEO compensation having grown 940 percent since 1978 while the average worker compensation rose by just 11.9 percent.12

In addition, national debt across the world is on a dramatically increasing trajectory. Since 2000, the world’s two largest economies have doubled their debt to GDP ratio (the U.S. from 55 percent to 106 percent, and China from 22 percent to 50 percent).13 Consequently, we have continuously overburdened the economic engine, and it is now sputtering and threatening to slow down significantly.

Unfortunately, with all the policy interventions implemented since the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, the whole focus of the financial industry and the political class has been on speculating how the market will recover—the quick and sharp recovery like a V, the moderate damage followed by recovery like a U, the double dip-shaped recovery like a W, or the pessimistic long-drawn recovery where previous highs will not be reached again like an L. Meanwhile, the excess liquidity and fiscal backstops are bringing some colour back to the market. Hence the hedonists’ victory conches and bugles are starting to sound once again with the DJIA back at 26,067 as of July 8, 2020.

What is probably being continuously ignored here is the fact that every such action that purports to reinvigorate the market is actually draining the last remaining drops of blood from the portrait, i.e., the economy. While the equity market is showing an almost V-shaped recovery, the economy is looking at an L-shaped future as the forecasts for most economies are continuously worsening. On April 6, 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had forecast that global GDP would contract by minus 3 percent and revised it further downwards to minus 4.9 percent by June 24, 2020. The probability of further downward revisions remains high. The hedonistic economic model has long focused on the performance of the market, and continues to celebrate the recovery of the DJIA while ignoring what the IMF had reported in June 2020—that the global decline in work hours in the first quarter of 2020 was equivalent to a massive 130 million full-time jobs being lost, and this was expected to worsen to 300 million full-time jobs being cut in the second quarter.

The way forward

There is an emerging belief that policymakers and political leaders need to shift their focus of attention. The time has now come where it is imperative that businesses should be focusing on the benefits of the firm and society, rather than just investors/shareholders. This is in line with the Stakeholder Theory, which can be considered an alternative version of capitalist thought. The theory focuses on the multiple interrelationships amongst the various entities that have a stake in the organisation—its customers, employees, regulators, investors, communities, etc.14

The IMF report of June 2020 finally acknowledges that “the extent of the recent rebound in financial market sentiment appears disconnected from shifts in underlying economic prospects”. It is extremely important now that the policy framework globally should place emphasis not just on the financial efficiency of the capital deployed by corporates and governments, but also on its overall efficacy in achieving societal objectives like employment and livelihood, social equality, job security, and reduction of financial uncertainty. Firms and businesses need to develop new models not just of operation and delivery to overcome the immediate challenge of Covid-19, but they also need to develop the right stakeholder-oriented business models. Corporations and businesses need to recognise that they have a responsibility towards their employees, the families of these employees, their vendors, the local communities where they operate, the national economy that they are a part of, and the global economy to which they are directly or indirectly related.

We are already seeing companies starting to announce lay-offs, which are being couched in public relations terms as “business realignments” necessary for their survival. This should be strongly disincentivised by regulators and policymakers. Companies need to provide high levels of confidence to their employees (and indirectly to their families) in terms of job stability. Firms like DBS Singapore have shown the way by pledging to protect the livelihoods of its employees in the short to medium term. Higher levels of employment will have a significant economic multiplier effect, and create a virtuous cycle of income-based consumption, which will provide robustness to the core economy. Firms need to dramatically reduce the wage dispersion and rebalance the slippery slope of management variable compensation. They should use their resources to create new jobs that will foster growth and build buffers for surviving economic cycles, rather than use low-cost liquidity to do share buy-backs and bolster equity prices.

The market has clearly thrived on the short-term focus of the management on profits, and the desire of the financial/regulatory apparatus to implement immediate fixes to keep it vibrant. The last few years have shown that the challenges of the hedonistic view of the market have become very difficult to manage and sustain. The events of the recent past clearly indicate that if the leaders of global finance and politics continue to adopt short-term, value- maximising solutions, this would once again lead to B2BAU as soon as the market stabilises and returns to its growth phase. Rather, the market needs to recalibrate its expectations with the new paradigm shift from shareholder to stakeholder.

As such, we need to reject the philosophy of market hedonism. The market today needs to undergo a mindset shift from prioritising shareholders to doing so for stakeholders instead. The pursuit of the narrow goal of financial value maximisation needs to give way now to a scenario for optimising across long-term financial value, in conjunction with sustainable economic fundamentals and equitable social objectives. The core economy is almost on its knees, and the world needs Dorian to sacrifice itself (the glory of the market) for the benefit of the economy. The transition has to be made from embracing the short-term stockholder maximisation view to adopting the stakeholder optimisation strategy. The exogenous responses in terms of monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policies that need to be taken now should focus on rebuilding the health of the economy, and not the beauty of the market. It is still not too late to do so.

Dr Ajay Makhija

was CEO of Global Consumer Banking at Samba Financial Group, Saudi Arabia from 2006 to 2015. Prior to joining Samba, he spent over 16 years at Citigroup working across India, Africa and other parts of Asia

References

1. Oscar Wilde, “The Picture of Dorian Gray”, 1891.

2. Steven A. Edelson, “Promethean Business: From Financial Hedonism to Financial Eudaimonia”, Journal of Management Enquiry, 2019.

3. Adam Smith, “The Wealth of Nations”, 1776.

4. Joel Bakan., “The Corporation: The Pathalogical Pursuit of Profit and Power”, New York: Simon and Shuster, 2003.

5. Yiannis Gabriel and Tim Lang, “The Unmanageable Consumer”, London: Sage, 2015.

6. “Household Debt to GDP”, Trading Economics, June 2020.

7. Spriha Srivastava, “Global Debt Surged to a Record $250 Trillion in the First Half of 2019, Led by the US and China”, CNBC, November 15, 2019.

8. Simon Gilchrist and Egron Zakrajsek, “The Impact of the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programs on Corporate Credit Risk”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 2013.

9. Lars E. O. Svensson, “Monetary policy after the Crisis,” Proceedings, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, November 2011.

10. Sarah Brown, Gaia Garino, Karl Taylor and Stephen Wheatley Price, “Debt and Financial Expectations: An Individual- and Household-Level Analysis”, Economic Inquiry, 2007.

11. Oxfam International, “62 People Own the Same as Half the World, Reveals Oxfam Davos Report”, January 8, 2016.

12. Lawrence Mishel and Julia Wolfe, “CEO Compensation Has Grown 940% since 1978”, Economic Policy Institute, August 14, 2019.

13. John C. Williams, “The Federal Reserve’s Unconventional Policies”, FRBSF Economic Letter, November 2010.

14. R. Edward Freeman, Jeffrey S.Harrison, Andrew C. Wicks, Bidhan L. Parmar and Simone de Colle, “Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art”, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.