The pandemic is likely to make long term changes to deglobalisation and medium-term inflation.

The human and economic toll of the Covid-19 pandemic cannot be overstated. In 2020, the global economy might deliver its worst peacetime performance since the Great Depression of 1929-31. Besides the short-term stresses and costs, the pandemic is likely to also have long-term implications for the global economy. It has already started to reshape the way business and leisure are organised and conducted. This is evident from the greater use of digital technology for aiding education and work-from-home arrangements. Leisure activities such as shopping and media entertainment are also increasingly being accessed via online platforms.

While these effects might reverse to some extent as the impact of the pandemic fades, there are two potentially long-term changes that are areas of concern not only for policymakers but also for the financial markets: deglobalisation and the backlash against global supply chains (GSCs), and medium-term inflation.

Global supply chains have powered Asia’s growth

The rapid growth of supply chains across borders has transformed global production and trade over the past 30 years. GSCs, coordinated by transnational companies, account for nearly 80 percent of global trade. The expansion of GSCs has contributed to rapid economic development in many emerging countries, particularly China, and has taken the emerging markets (EM) share of world exports to more than 50 percent. But globalisation and the expansion of GSCs has slowed since the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC), as countries have turned more protectionist and inward-looking in a bid to address slower growth, rising unemployment, and widening income inequality.

The Covid-19 pandemic threatens to undermine the importance of GSCs even further. The vulnerability of ‘just-in-time’ production processes around the world was illustrated by the shutdown of China’s Hubei province in early 2020 after a serious Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, the provincial capital. This vulnerability is now becoming a political issue as governments turn their attention to the shortcomings of their healthcare systems, with insufficient medical supplies within easy reach. This drive for ‘health autarky’ could spill over into other industries also deemed to be of national importance.

European Union (EU) countries, for example, have already been calling for greater ‘manufacturing sovereignty’ at both the national and EU level. At the same time, the U.S. administration has adopted an ‘America First’ policy based on the view that trade is a zero-sum game—implying that if other nations are benefiting, it must be at the expense of the United States. The political resistance to globalisation has also grown since the GFC. Rising inequality, particularly in advanced economies, may have been driven more by technological change than by increasingly complex supply chains, but globalisation continues to take much of the blame in political discourse.

This is already reflected in export curbs and a desire to make essential products locally, so as to reduce export dependence. For example, in response to the Covid-19 outbreak, over 50 countries have imposed export curbs on medical supplies since March this year. This highlights how the changing global environment has resulted in more restrictive trade policies.

FROM JUST-IN-TIME TO JUST-IN-CASE SUPPLY CHAINS

Whether rising protectionism or pure economics is to blame, concentration risk may now become the dominant focus. A supply chain that is dependent on a single source (even for one small part of a product) is vulnerable to paralysis when that source gets cut off. It takes 2,500 components to make a car, but just the lack of one component to not make a car. Company boards will thus need to take concentration risks more seriously going forward. The result may be a shift in inventories away from highly efficient but vulnerable (just-in-time) to more capital-intensive (just-in-case) processes. Most manufacturing firms typically keep only two weeks’ worth of inventories. A just-in-case approach would lead to a shift away from the current model of lean inventory management to one that focuses on stocking up.

HOW WILL GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAINS EVOLVE?

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the weaknesses in how GSCs are currently structured. Digital technology, including robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence, is also making it easier to bring back production onshore or shorten supply chains to lower the risk of abrupt stops in production. We expect a few changes to become more evident over time:

1. Greater transparency

Anecdotal evidence suggests that supply chains have become so complex in some cases that firms are unaware of their exposure to different countries or suppliers. We expect a greater focus on transparency and data-sharing on how GSCs are structured to identify and minimise bottlenecks. In addition to traditional considerations such as cost and quality, there will be an increasing emphasis on the ‘three Rs’—resilience, responsiveness, and reconfigurability—to determine how GSCs should be structured.

2. Trend towards ‘just-in-case’ inventory management

Over the past few decades, the fall in transport and communication costs, as well as the use of technology, has allowed firms to maintain very lean inventories—a ‘just-in-time’ model of inventory management. This is likely to change as firms face huge uncertainties not only over pandemics but also tariff wars, which would suggest a shift towards the ‘just-in-case’ approach.

3. Emergence of shorter regional supply chains

Firms are likely to prefer moving their production to local sites. However, cost and quality considerations are likely to mean that the process will be staggered, with a move to more diversified sources (from dependence on a single source) or to centres that are geographically closer to reduce the possibility of disruptions. Since 2012, the share of foreign inputs that cross-border supply chains source from their own region has risen in North America, the EU, and Asia. This is likely to accelerate in the coming quarters. It is, in fact, already reflected in stronger intra- regional foreign direct investment (FDI) flows.

FOCUS ON REDUCING CONCENTRATION RISKS

A focus for many governments since the start of the pandemic has been to determine whether specific supply chains (especially for critical products) are overly dependent on any single country, and to take measures to reduce this dependence. This might prompt some countries to seek a smaller role for China in their supply chains. Over the past couple of decades, China has cemented its role not only as a mega- trader but also as the key hub around which GSCs are centred. The country’s share of global manufacturing of intermediate products has risen to 20 percent currently, from just 4 percent in 2002.

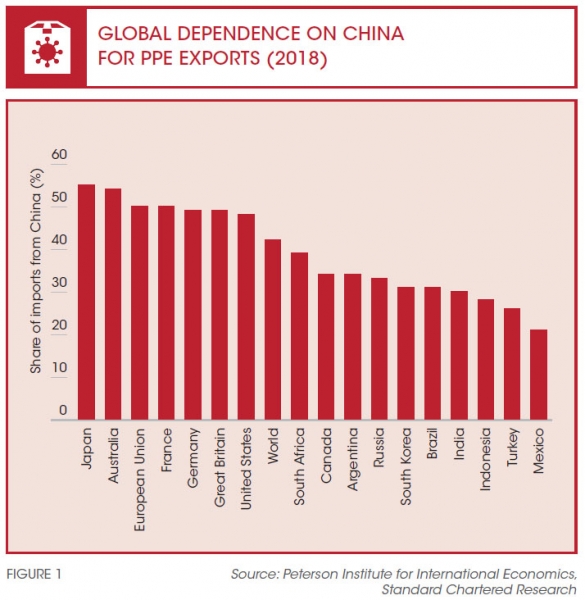

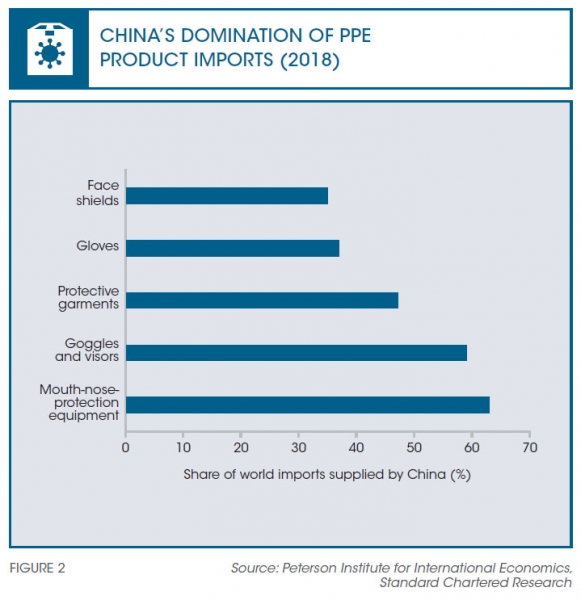

In the immediate future, countries are likely to focus on lowering their significant dependence on China for the key medical supplies needed to fight the pandemic (refer to Figure 1), while protecting their own supplies through export curbs. According to research by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), China in 2018 accounted for 42 percent of the world’s supply of face shields, protective garments, gloves, mouth-nose-protection equipment, goggles, and visors—all the essential personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to fight the pandemic (refer to Figure 2).1

It is likely that countries will increasingly focus on other products for which China is the main player in the GSC. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, China has a share of over 50 percent in the GSCs of several manufacturing products. These include precision instruments, automotive and communicative equipment, and machinery products.

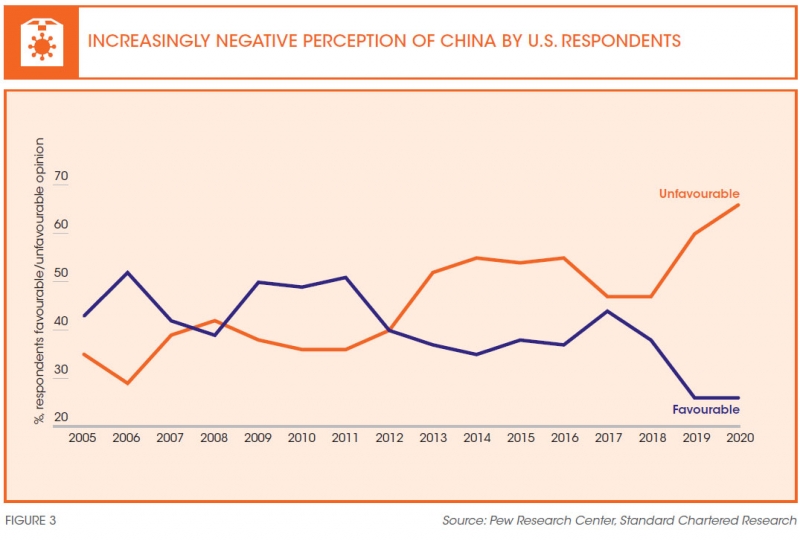

Meanwhile, growing political rhetoric against China’s central role in global trade seems to be gaining wider public support. In a March 2020 survey by the Pew Research Center, a significant majority of respondents in the U.S. viewed China more negatively after the start of the pandemic (refer to Figure 3).2 This also translated into a higher proportion of respondents now viewing China’s influence and power as a ‘major threat’ to the United States.

SOUTH-SOUTH TRADE LIKELY TO SUPPORT GLOBALISATION

Deglobalisation for many countries is likely to equate to reducing dependence on China. However, China’s dominance of world trade is unlikely to be challenged in the near future. In fact, its growing importance as a source of FDI for other EMs (for example, via the Belt and Road Initiative) is also likely to help it maintain its position as a mega-trader.

In addition, while the shift towards regional supply chains is becoming clearer, factory relocation tends to be a multi-year project involving long planning times and heavy investment. The current macro backdrop is probably not conducive to making such commitments.

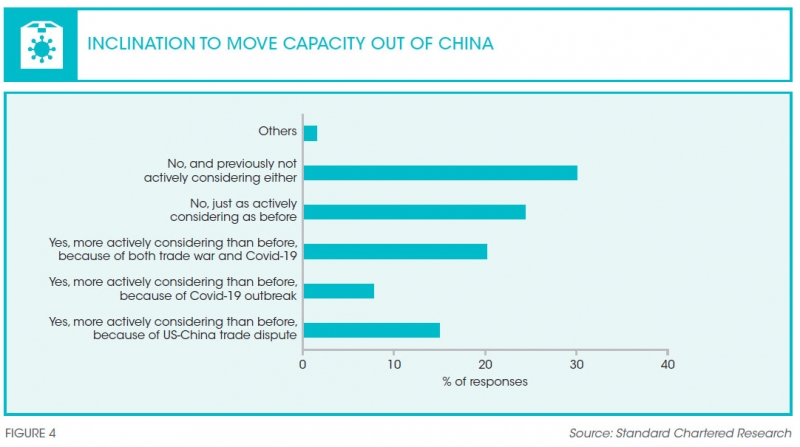

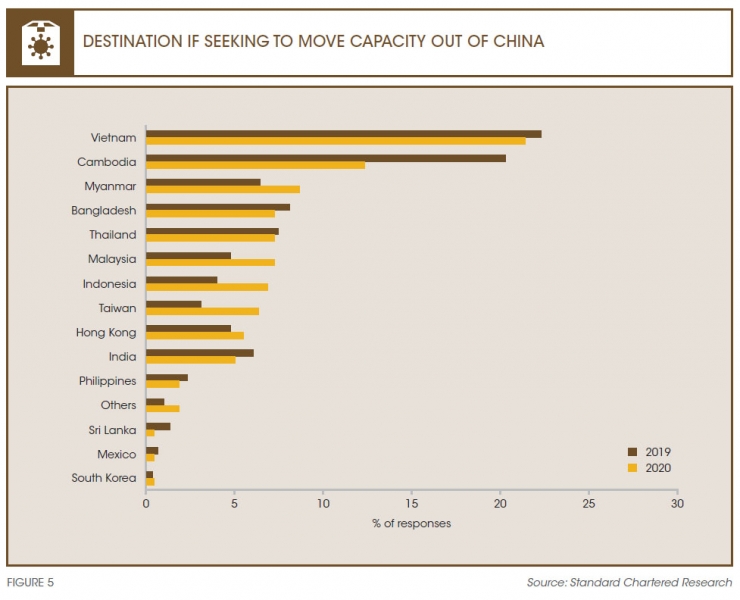

Our latest proprietary annual survey of manufacturing firms based in the Pearl River Delta region in China, conducted earlier this year, showed that 43 percent of respondents are actively considering moving their capacity away from China due to the U.S.-China trade tensions and/or Covid-19 crisis (refer to Figure 4).3 These developments have raised worries that manufacturers operating in China face a high concentration risk. However, respondents are motivated by a desire to diversify their operations rather than to completely relocate their existing China production, which is seen as unrealistic. If we add to this another 24.6 percent of respondents who are not swayed by the trade war or Covid-19, but are still actively considering relocating overseas, then close to 68 percent of respondents were planning to relocate out of China. Among them, 19 percent have already moved and started operations; a sizeable 45 percent were in the ‘still under consideration’ phase. Firms that are looking to move out of China are planning to relocate production not back to developed markets (DMs), but to low-cost countries in the ASEAN region, led by Vietnam (refer to Figure 5).

Inflation: Back in the saddle again?

Another key change being increasingly discussed by market participants is the likelihood that the pandemic will end the current low-inflation era and inflationary pressures will start to rise again. This will have implications for financial markets and the conduct of economic agents, as well as policymakers.

COST-PUSH INFLATIONARY PRESSURES EXPECTED TO RISE

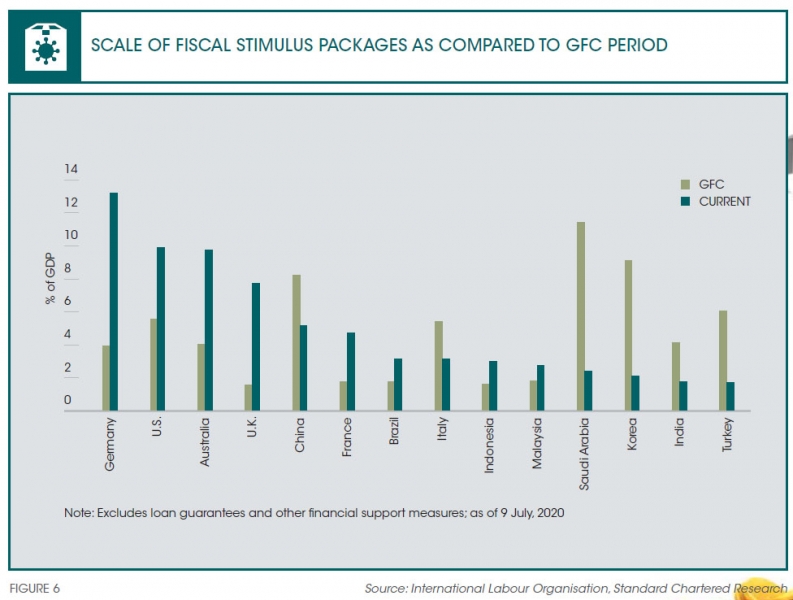

Deglobalisation and disruptions to GSCs, which have the potential to lower cost effectiveness and push prices higher, are seen as a potential factor supporting higher inflation in the medium term. More importantly, major central banks have responded aggressively to the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, cutting policy rates to the zero lower bound and expanding balance sheets at an unprecedented pace. Governments have also been quick to respond with significant stimulus packages, which are much larger than those seen during the GFC (refer to Figure 6). The sheer scale of the response has reignited the debate on whether inflation is likely to rear its head again, after nearly three decades of easing inflationary pressures. A growing chorus of academics and market analysts believe that the combination of these factors is likely to mean an end of the era of ‘lowflation’ in the global economy.

FISCAL POLICY IS THE GAME- CHANGER

We think the most compelling argument in favour of higher inflation is the more aggressive use of fiscal policy (in conjunction with monetary policy) to support growth. This is clearly a risk to our view of lowflation over the coming years.

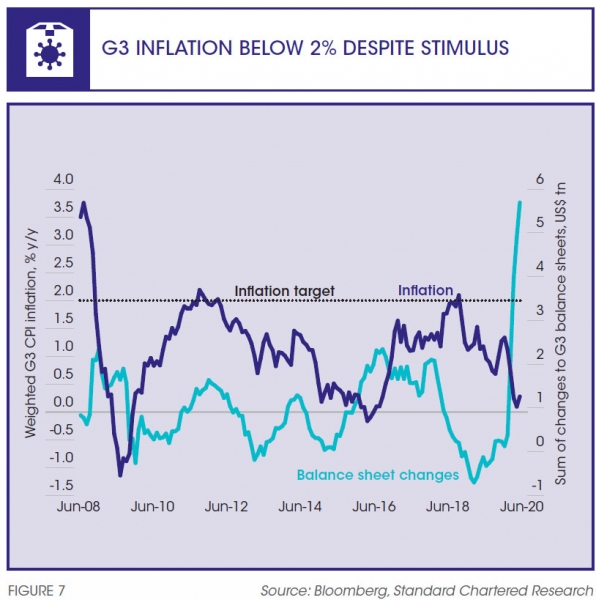

Central banks have opened the floodgates of liquidity into the system by significantly expanding their balance sheets. This concerted central bank action over the past 10 years has been dwarfed by central bank commitments to balance-sheet expansion since the Covid-19 pandemic hit the global economy. However, we are cautious about assuming that balance-sheet expansion will lead to higher inflation. Despite large quantitative easing being undertaken by central banks over the past decade, inflation in the major G3 economies—which include the U.S., the Eurozone, and Japan—has remained well below central bank targets or goals (refer to Figure 7).

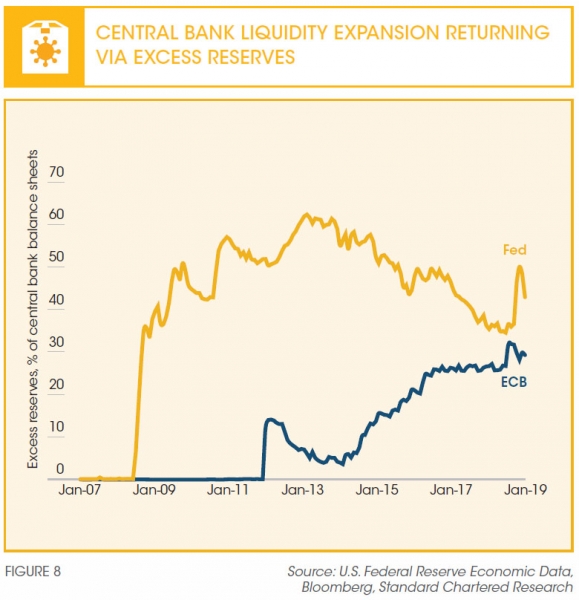

A key reason for this limited effectiveness was that commercial banks chose to store extra liquidity back with the central bank in the form of excess reserves, rather than lending it to the real economy (refer to Figure 8), resulting in a drop in the ‘velocity’ of money. The data so far suggests that this situation persists today as demand for investment loans remains weak, and excess reserves with central banks continue to rise. At the same time, just as uncertainty over job prospects and the health of the economy has risen, so have the levels of precautionary savings.

Fiscal stimulus could be a real game- changer over the medium term and the biggest risk to our view of continued low inflation. However, the stimulus packages implemented so far are meant to be temporary and are aimed largely at replacing lost demand due to the pandemic. Governments are still worried about high leverage; we expect nascent signs of economic recovery to be accompanied by renewed talk of austerity and the need to reduce high indebtedness across major economies.

INFLATION IS A GREATER RISK IN EMERGING MARKETS

Inflation in EMs has remained mostly well-contained since the mid-1990s. Average inflation (excluding outliers) has declined from high double digits in the 1980s to single digits, driven by prudent monetary policy and fiscal consolidation. While inflation is likely to remain well contained in the medium term, risks are skewed to the upside. Structural factors supporting lowflation in DMs, such as ageing populations, are less in play in the EM space. The use of unconventional monetary policy, dependence on commodities, and the rise of the middle class could all push inflation higher. On the other hand, rising deglobalisation could lead to job losses, thereby weighing on inflation.

UNCONVENTIONAL POLICY IN EMERGING MARKETS COULD PUSH INFLATION HIGHER

Central banks in several EMs have successfully adopted unconventional monetary policies during the Covid-19 pandemic without spooking financial markets. However, if EM asset purchase programmes turn more aggressive to match those of their DM counterparts, this could fuel concerns about the risk of debt monetisation. Fiscal spending in several EMs has been constrained by the lack of fiscal space; debt monetisation could lead to a significant increase in fiscal spending, fuelling inflationary pressures. But less mature EM institutional frameworks increase the perceived risk (among investors) of debt monetisation, fuelling worries of higher inflation through excessive printing of money and subsequent spending.

Looking ahead

We expect to see inflationary pressures over the next year or two as the recovery takes hold. This is also likely to fuel expectations of sustained overshooting of targets even in the medium term. However, we take a cautiously contrarian view and expect the global economy to remain in lowflation over the medium term. Structural forces that have supported weak inflationary trends—such as high leverage, ageing populations, and rising income inequality—will continue to exert downward pressure on inflation, in our view. In addition, while deglobalisation and supply chain disruptions in a post-Covid-19 world are likely to be inflationary in the short run, we also expect them to spur the move towards greater automation and use of robotics in supply chains over the medium term. The falling cost of such technology adoption is likely to make such moves easier, while keeping cost-push inflationary pressures under control.

Despite the substantial policy stimuli recently, it would take a dramatic change in monetary-fiscal policy regimes for economic agents to revise their medium-term inflation expectations. Authorities would need to signal that they plan to move away from an inflation-targeting regime (not just tweak it to reflect average inflation targets, or similar moves) and/or signal comfort with much higher deficits and debt levels. So far, there seems to be little appetite for this. In fact, in the U.S., there is already disagreement over the size and form of further fiscal stimulus, despite the fact that a solid growth recovery has not yet occurred.

Inflation is likely to be a bigger risk in EMs; the use of unconventional policy could push inflation higher. We also expect US dollar weakness to be reflected in stronger EM currencies, but risk aversion driven by geopolitical events could easily reverse this. Higher imported inflation, through weaker currencies or more expensive imports, could push up inflation expectations in EMs. Higher commodity prices could also push headline inflation higher in the medium term. The recent drop in crude prices will likely cause supply losses as investment is postponed and rigs are closed.

With food and fuel accounting for 30-60 percent of consumer price index baskets in EMs, EM central banks might be less willing to accommodate a commodity-driven spike in headline inflation. On this front, it will be important to closely track China’s efforts to rebalance its economy away from an export- and investment-led (commodity-intensive) model to a consumer-led economy. A renewed focus on rebalancing would help to lower commodity demand to match the expected fall in supply, given China’s status as the world’s marginal commodity buyer.

Madhur Jha

is Senior Global Economist at Standard Chartered Bank, India

Chidu Narayanan

is Economist, Asia at Standard Chartered Bank, Singapore

References

1. Chad P. Bown, “How the G20 Can Strengthen Access to Vital Medical Supplies in the Fight Against Covid-19”, PIIE, April 15, 2020.

2. Pew Research Center, “U.S. Views of China Increasingly Negative Amid Coronavirus Outbreak”, 2020.

3. Standard Chartered Bank, “Shop Talk–GBA, Covid-19 and Shifting Supply Chains”, 2020.