The success of any intervention is achieved by winning over the support of staff and aligning team members who are driven by different professional agendas.

Despite the buzz and a vast number of books and articles on change management, nothing quite prepares you to undertake that journey. Early in my professional career, I was tasked to lead a change management team to drive the transformation strategy that the organisation I worked for wished to implement. After a few days on the job, it slowly dawned on me that it is not as sequential and structured as it is made out to be in the many books I have read and training sessions I have attended.

Change management has an immediate impact on personal relationships. When you start to initiate change, you lose your friends in the organisation! You are now looked upon as an agent of the CEO. Your colleagues are uncertain of your mandate, making them apprehensive and suspicious of your role and the special relationship that you have with the leadership team.

Organisation transformation projects are complex, particularly if they are coupled with new business models or technology implementations. Unfortunately, the practice of change management has been much abused. Many have peddled a set of communication templates and turned the practice into a checklist of activities, the completion of which signifies a successful change programme.

The success of any intervention, however, is achieved by winning over the support of the employees and aligning team members who are driven by different professional agendas, varying levels of morale and motivation, personal agendas, and perhaps, political scheming. These agendas drive them to specific unconstructive behaviours that derail conceptually well laid-out plans.

Any communication targeted at employees will typically trigger a cautious response as they look for the hidden agenda, the underlying objective that is not explicitly stated. They often doubt the very purpose of the intervention. Ultimately, these uncertainties seed the beginnings of the resistance to change. While communication does play a critical role, town hall meetings, mass email communications, and posters plastered along office corridors do little to remove apprehension. These are top-line activities that ‘project’ that the change agent is doing some work and that the organisation is going through a transformation.

But it is not as if people just get up in the morning and say, “Today I will resist change.” Instead, they are reacting to the unanswered questions: What is the leadership agenda? How will it impact me? Will I be successful in my new role? Will I need new skills? Will I be made redundant? These unanswered questions and unaddressed doubts manifest as mistrust and anxieties that eventually play out as resistance.

Burnt bridges, or…

The first task for any change manager, therefore, is to gain the trust of employees and colleagues. The change manager has to be seen to be on the same side of employees, and this shift is achieved when staff feel that the change manager is deserving of their trust. The change manager must revisit and rebuild bridges to create the bond of believability.

The change agent must be empathetic towards people and be able to naturally structure ambiguous inputs into a structured strategy or plan; someone who is willing to constantly re-evaluate strategy and be flexible to change. More importantly, the change manager should be a coach ensuring that teams win and get recognised for their success. Moreover, it is highly advisable that the team has several immediate victories to celebrate as a means to gain momentum.

To be successful in the corporate world, employees need to project themselves, stand out and be visibly seen as people who get things done, inspiring others to deliver actionable outcomes. But for a change agent, the reverse is true. The greater the spotlight on the change agents, the lower are their scores on credibility. Employees start seeing such change managers as those who are focusing on their personal agenda, driving their popularity, and projecting themselves, rather than being concerned about the employees and how they will survive the change.

There is no single prescriptive formula for bringing about change in an organisation because each individual is different, and we all behave differently in different groups. Besides, the cultural group dynamics in every organization are also special. Change management therefore is not a practice where one size fits all. It needs to be adapted, improvised and then fitted to the needs and demands of the organisation. Change programmes almost never follow a linear path. The teams that manage change have to constantly modify their approach and manage processes to ensure that change is aligned to the expected outcomes. For this, it is key to understand the underlying dynamics that come into play.

Working up the levels

In the context of change, the primary focus for the organisation is not its businesses, profits, products, services or brands—but its people. And people are driven to organisational change when it is aligned with their personal and professional aspirations. Therefore, before evaluating the impact of change on business, change must first be made relevant across all levels of employees in the organisation. Employees must be provided clarity on how the change will impact their current roles, and consequently how they will be supported to succeed in their new roles, or else resistance becomes the natural outcome. If this happens, the change investment will naturally spiral downward.

The change process may result in new responsibilities and accountabilities, and even redundancies. Added to this, employee fears include loss of power, loss of control, and loss of reporting relationships. This differs according to the different levels of hierarchy that exist in an organisation. At the ground level, the issues surrounding change are largely about being made redundant or acquiring new skills. These concerns can be easily addressed and hence effectively catered to.

As we move to middle management, complexities arise. Managers, by definition, are ambitious people. They are in a position to drive agendas for their own teams and for their own professional growth. The position that a change manager should take here is to project that he/she is supporting middle management for their success. The change taking place needs to be aligned to the agendas of teams in middle management, not his/her own.

The senior leadership band has a very different perspective of this change. Most organisations at the leadership level are inherently political. Typically, senior leadership teams have deeper and more significant ties with a larger circle of power they wish to protect, and change here is far more unsettling. The change agent must work nimbly and strategically on the change manifesto when dealing with the senior leadership teams. To do this, he/she requires a good understanding of power equations, be sensitive to personal dynamics, and develop insights into the interplay of team mechanics while operating in the landscape of change. The capability and muscle to manage dissonance without compromising the campaign is a behavioural sensitivity that the change agent must rise to.

In addition to understanding and working with each level of the organisation, the change agent also needs to be aware of any conflict that might exist among the hierarchical levels. Middle management plays an important role here. To look good in front of their bosses, middle managers typically attempt to camouflage the weaknesses of their teams. The task of the change agent is to identify the most critical barriers that are impacting the ability of the teams to deliver the desired outcome or make the required change, and then design ways to overcome these obstacles.

The change maker

A change strategy is employed for progress and for the larger good. But not every organisation is able to execute strategy to achieve success. The change agent is not just a communicator or deliverer of change but is responsible for diagnosing the challenges and implementing changes to overcome those challenges.

Therefore, the change agent is a mixed bag of professionals rolled into one. Sometimes a guiding mentor, at other times a supportive coach, and then, a resourceful and knowledgeable management consultant. Along with these characteristic abilities, and sometimes, cultivable traits, the change agent must have the necessary mandate and backing of the leadership to manage escalation and establish authority to deliver a transformed organisation.

GETTING THE BUY-IN: CAN YOU FIND SOMETHING IN YOUR CHANGE THAT MOTIVATES?

If you want to communicate a change or conduct a change management workshop, most managers will say that they don’t have time for it. But if you say you want to talk about how they can increase sales by a certain percentage, they will be much more open to the discussion because it impacts their business directly. They will then look at the change agent as a collaborator and an enabler to achieve the desired outcome.

Once the discussions start, the team, as a group, will face organisational challenges related to skills, resources, structure, relationships—and those are the hostilities that one needs to tackle to bring about change. Team-building activities and workshops have their place, but that is not the main role of the change agent. It is not the job of a change agent to create a feel-good environment, but rather to get into the actual nitty-gritty of each business and to work on improvement. Once the actions and outcomes are identified, they need to be raised to the leadership.

PRESSURE TO PERFORM: QUICK WINS GAIN SUPPORT, SUPPORT CREATES THE MOMENTUM TO PUSH THROUGH

The change agent works through a tangle of complexities that come in the form of people and processes. While there is an outcome in mind, does it test the patience of the organisation? Is there pressure to show results, or at least show some intermediate results? It is very difficult to show that everything has fallen into place; every change will have mixed results. But it is also necessary to have some quick wins. Instead of focusing on the change, one needs to focus on what is hindering the success of the organisation and then take steps to remedy that. Change will happen automatically.

ACCOUNTABILITY: PUTTING NAMES IN THE ORGANISATION BOXES DOES NOT ENSURE THINGS ARE GETTING DONE!

When we create an organisation, we logically put together a set of tasks and then assign a group of people to perform those tasks. And when we replace person A with person B to perform a task, we assume that the task will be performed in the same way with the same level of efficiency. But individuals are not all structured the same way. Each brings a different level of skills and strengths to a task. So, trying to force people to take up specific tasks or activities creates the classic dilemma of fitting a square peg into a round hole. On the other hand, no organisation can afford to become so free-flowing as to let every employee choose work based on what they like, instead of what they are good at. But it is feasible to achieve something in between. While all employees will have an assigned role to deliver as their primary job function, there could be some free-flowing tasks that can be taken up according to their innate strengths and interests.

This dual role that an employee plays ensures a twofold benefit for the employee and for the organisation. First, it creates excitement and motivation because the person is assigned a task, which he/she enjoys as it is compatible with his/her skills and strengths. At the same time, he/she continues to enjoy the security of the existing job. By leveraging on the employee’s natural strengths, morale flourishes and motivation is at its peak, allowing for employees to deliver stretch goals; they are willing to go the extra mile because they are energised by doing what they are intrinsically good at. In this way, they can explore their interest and passions within the safety of their existing jobs. In this positive environment, employees start accepting and even adopting change because they see a benefitin the change for themselves.

NOURISHING AND SUSTAINING CHANGE: IT’S A CONSTANT

Lastly, change is not finite; it is a continuous process of improvement and new successes. The moment we treat change as a one-time activity that has an end date, we stop giving it priority and tend to revert to the old ways of doing things. So sustaining change is very important to keep the momentum going. If there are some good things that have been brought about—tangible, positive change—then it is important to keep those alive. Business as usual should not be an option. It is easier to maintain existing momentum than to restart a change process. Keeping the good things that work provides the fuel and energy for the next big thing the organisation is aiming for.

MAKING IT REAL In the organisation I worked with, there was a person in an operations role, designated as the Warehouse Manager. His job scope involved managing supplies in a warehouse. While he managed his job diligently, his sedentary job of sitting in the warehouse doing routine work had long lost its shine. During the diagnostic interviews, the change agent, wearing the dual hat of a mentor and a coach, was able to find that this employee harboured secret aspirations of interacting with people and desired a more client-facing role. This Warehouse Manager, in addition to managing his seemingly humdrum job, was given the opportunity of taking up a sales role within the company. He was able to find inspiration in his new role, and constructive energy was unleashed. This energy translated into enhanced performance in other areas as well. This example of employee deployment is a lighthouse case that can serve as a model for other similar projects, where the impact of a change intervention goes deeper than just employee engagement. It demonstrates that if executed well, change management gives flight to personal aspiration and long-term personal growth. |

Six key learnings for driving successful change management

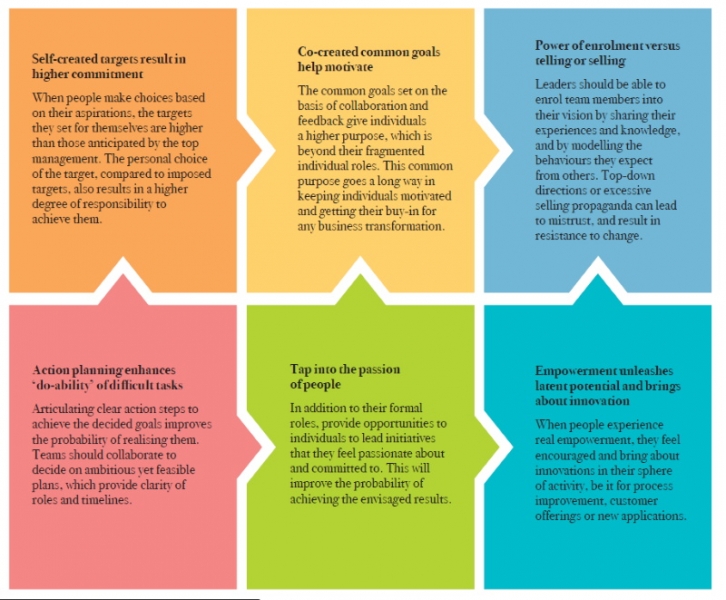

There are some key guiding principles that change agents must believe in if they are to be successful in driving change.

Given the variability and complexity of organisations, it is unsurprising that change agents often simplify the engagement into a series of structured tasks and hold themselves accountable to accomplishing them instead of focusing on the desired outcomes of change. This is a key reason why, despite all the literature and content on change management, very few succeed in reaching the goals that an organisation sets out to achieve.

Lalit Jagtiani

is a Business Transformation Specialist and a Thought Leader in Digital Strategy at SAP, Singapore. He is also an author of the book, “When Change Happens: A Story of Organizational Change"