Culture’s impact on creativity and ways to boost it.

A crotchety American named Henry Ford invented a modern, fast and efficient way to manufacture automobiles and a Japanese man named Eiji Toyoda refined and perfected it. A series of innovators across the western world developed the television—and the tech specialists at Sony, Toshiba and a host of other Asian companies found ways to make TVs better, cheaper, faster. And an idiosyncratic Californian named Steve Jobs invented a company that made a smart phone for the masses—and then outsourced the manufacturing to China.

If you detect a pattern here, you are not alone. Asia may be the home of some of the world’s hottest economies, but it is not the home of the world’s hottest inventions. Although Asia has been innovating, its innovations tend to be incremental,1 lacking global reach and impact. Admittedly, there have been some Asian breakthroughs from time to time (e.g., Chinese scientist Tu Youyou won the 2015 Nobel prize for medicine for her discovery of artemisinin and its treatment of malaria), but these are more exceptions than the norm.

And people are noticing. Ng Aik Kwang, a psychologist who specialises in teaching creativity in Asia, wrote an entire book about it called “Why Asians are Less Creative than Westerners.” Meanwhile, Kishore Mahbubani, dean and professor in public policy at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, wrote a book on the same topic with a title with all the pithiness and politesse of a Donald Trump tweet. It’s called: “Can Asians Think?”

And none other than the late Lee Kuan Yew, the technocratic genius who invented modern Singapore, noted that a lack of creative ability could hold China back. “China will inevitably catch up to the U.S. in GDP,” he told Time magazine in 2013. “But its creativity may never match America’s because its culture does not permit a free exchange and contest of ideas.”

That may be true, but it’s also quite likely that the challenges limiting creativity among Asians run far deeper than any one country’s politics. Instead, the roots of the Asian creativity chasm can be found in Asian culture—and research indicates that it’s a chasm that can be closed. All it takes is a little more worldliness and tolerance, a little creative conflict, and a lot of leadership.

The importance of creativity

Before we explain, though, it is important that we grasp the importance of this issue.

In the business world, success stems from innovation, and in an era of rapid technological advancement and global competition, innovation matters more than ever. To have innovation, however, one must first have creative ideas. Innovation is the successful implementation of creative (novel and useful) ideas.

The proof of that can be found in volumes of industry research. For example, a 2010 survey of 1,500 CEOs from 60 countries, conducted by IBM, found creativity to be the most important leadership quality. Similarly, a 2011 survey conducted by MDC Partners and its Allison & Partners subsidiary found that 76 percent of CEOs surveyed cited creativity as one of the top elements that would help their business in the year ahead. And Spencer and Stuart’s 2014 survey of more than 160 senior marketing leaders found that 70 percent said creativity is just as important as analytical ability in performing the job well.

Perhaps most impressively, though, a 2014 executive study conducted by Hyper Island in cooperation with Edelman Public Relations delivered a detailed endorsement of creativity as the key quality that would make companies thrive in the coming years. This “Tomorrow’s Most Wanted” executive study polled more than 500 top business leaders and employees, measuring perceptions of future challenges over the next three to five years and the skills and qualities needed to meet them. The most desired personal qualities were drive, creativity and open-mindedness, while the top skills were problem solving, idea generation and developing creative technology.

In this article, we focus on the impact of culture on creativity, the precursor to innovation. We begin by exploring the creativity challenges that Asia faces; we then discuss new research that informs us on how cultural norms in Asia might play a role. We conclude by offering some recommendations for individuals and organisations to boost creativity in Asia.

Do Asians lack creativity?

Given the importance of creativity for success in the 21st century, how well are Asians poised for the future, then? Not so well.

Recent history and recent research both show that Asians lag behind westerners in creative thinking. The landmark inventions of the past century—antibiotics, the personal computer, the Internet—all were developed in the West. Cultural products that have worldwide followings are still dominated by Hollywood and western studios. Moreover, creativity research performed by psychologists—which compares Asians with westerners on their performance when asked to complete various tasks requiring creativity—frequently concludes that Asians are less creative than westerners.2, 3

Of course there is no biological reason why this would be so. The basic neurological processes required for creative thinking are present in all human beings, so it is not as if Asians lack a certain gene or the neurological wirings required to innovate. What’s more, things were not always that way. Looking back through the millennia, and you will see that the Chinese invented gunpowder, the compass, paper and printing technology. If Asians were indeed so innately uncreative, how is it that they can come up with some of the most important inventions our world has seen?

Asians have not come up with such innovations lately though, and it could be partly because history got in the way. For a multitude of reasons ranging from isolationism to poor leadership, China fell into a 500-year decline from which it has only begun to emerge in the past 40 years. Meanwhile, the West took the lead in the industrial revolution and extended its domain across several continents through a period of colonisation. And on top of it all, Asian countries suffered serious setbacks in the wars taking place in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that institutional environment also plays a role. For instance, the lack of strong intellectual property protection in some Asian nations might dampen the drive to innovate. In parts of Asia that are still developing, there might not be enough resources or governmental support for research and development.

Yet history and lack of a supportive institutional environment cannot fully explain why repeated research shows Asians to be generally less creative than westerners. Psychological studies seem to indicate that if Asians are indeed less creative, then it is most likely a learned behaviour, deeply rooted in their culture—values and norms they endorse. And it is rooted, perhaps, in the work of Asia’s greatest philosopher.

To understand Asian culture, we need to understand Confucianism. Many parts of Asia, and East Asia, in particular, are heavily influenced by Confucianism. The great Chinese thinker and teacher stressed the value of key virtues such as benevolence, righteousness, loyalty, wisdom and propriety. Confucius also emphasised the importance of five cardinal relationships: ruler and subject, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger brother, and friend and friend. Confucius believed that these relationships regulate day-to-day behaviours and motivations. In addition, these principles still greatly inform much of Chinese thinking—and therefore significant aspects of Asian thinking—2,600 years after the great philosopher’s birth.

Asia is a vastly diverse continent, of course, and we should be careful about lumping all Asian countries together, but many Asian countries do share similar cultural characteristics. Most Asian nations emphasise collective good over individual gain. They tend to be more hierarchical than western cultures. And Asian cultures tend to stress social harmony and the avoidance of conflict.

The trouble is, those characteristics do not necessarily encourage innovative thinking. Evidence for that can be found in a study done in South Korea. The researcher found that Confucianism may present cultural blocks to creativity. The study argued that people infused with Confucian thinking are loyal, obedient and hardworking—but less fun, less imaginative and less creative.4

In other words, Confucianism seems to have bred a culture of conformity, which, in the parlance of modern-day scholars, correlates with a concept called ‘cultural tightness’. Cultural tightness is a measure of the extent to which a culture or society relies on strong rules and norms regulating behaviour, as well as the extent to which deviations from those norms are sanctioned, as opposed to tolerated or even encouraged.

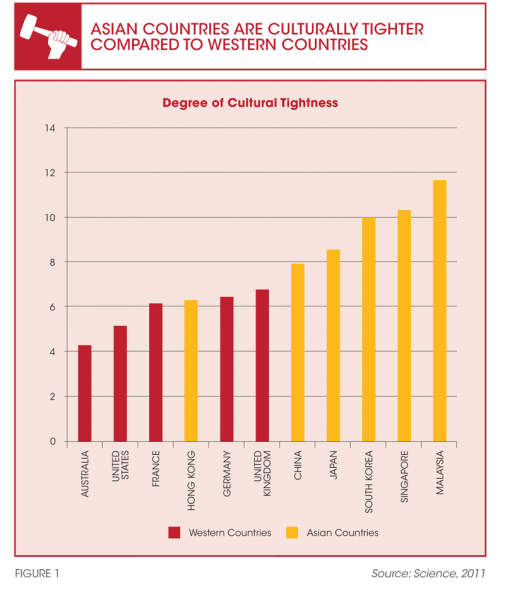

By those standards, Asia is a pretty ‘tight’ place. In a ranking of 33 countries in terms of cultural tightness, a 2011 study by Michele Gelfand, a University of Maryland psychologist, found that the five tightest countries were all in Asia.5 The region’s two economic powerhouses, China and Japan, ranked in the top 10 (out of 33). And the only Asian locale to qualify as more culturally ‘loose’ was Hong Kong, long a British colony (refer to Figure 1).

Yet when it comes to creativity, cultural tightness matters. Evidence can be found in a recent study the first author conducted at a creative crowdsourcing platform based in Paris, which allows people to enter ‘creative contests’ to help companies find innovative solutions to their business problems.6 The research revealed that people from tight cultures are less likely to enter and win creative contests overseas than those from loose cultures.

Why might that be so? The authors reasoned that it is partly because people growing up in tight cultures are heavily influenced by institutions such as their schools and the government. That has conditioned them to become ‘prevention-focused’—meaning they are very cautious and concerned about not making mistakes. This psychological adaptation prevents them from becoming innovators when it comes to creative problem solving. To be an adaptor, that is, to simply tweak existing solutions, is safer.

This research also found that tight cultures are less receptive to foreign ideas. Because of their society’s adherence to strict/narrow local norms and rules, people in ‘tight’ cultures tend to think more narrowly and less globally. This is particularly worrisome in the modern globalised economy, where increasing numbers of companies need to appeal to customers beyond their national borders.

In addition, ‘tight’ countries tend to create their own obstacles to innovation: rules and regulations that conflict with the creative process. Countries such as Singapore take innovation seriously and have invested heavily in it, yet its innovation output is not proportionate to the vast investment the country pours in, resulting in low innovation efficiency.7 It is not easy to innovate in a place like Singapore because there are many rules and norms regulating behaviours. For example, socially sensitive topics such as homosexuality and religion are carefully monitored and sanctioned in artistic productions. You need to know what these rules are, and how to navigate them, before you can innovate successfully.

Nevertheless, there is a bright spot. Our research also found that individuals from tight cultures are good at innovating locally or in countries that are culturally similar to their own. Indeed, a lot of the innovations we see in Asia today are highly localised, garnering success within the region. For example, Korean-pop cultural products such as dramas, music and movies are highly successful in South Korea and across much of Asia, and to some extent the Middle East. Yet, with the exception of PSY’s viral ‘Gangnam style’ music video, few Asia cultural products have a truly global reach.

All of this leaves ‘tight’ countries— i.e., most Asian countries—in a bind. Creative ideas and new products will drive the economies of the future, yet many Asian countries are stuck in a culture that leaves them serving as the factory or the back office for the developed world. When Asian countries do innovate, success tends to be localised, with limited global impact and reach.

Boosting creativity in Asia

The good news is that research indicates ways to break this bind. All it takes is a willingness to embrace diversity (and loosen up), to learn to love a little conflict, and to lead in a way that encourages creativity. Below, we elaborate how these approaches can help individuals and organisations boost creativity in the Asian context.

EMBRACING TOLERANCE AND DIVERSITY

Leaders can begin with the realisation that tolerance matters (a lot). More than a decade ago, Richard Florida’s book “The Rise of the Creative Class” ranked tolerance as one of the ‘three T’s’ that are key to creativity, the others being talent and technology. Florida saw tolerance—that is, the willingness to accept differences—as a key to attracting talent, but the research on cultural tightness and creativity described above suggests that a tolerant workplace also opens the minds of the people who work there, enabling them to think more creatively. Put differently, tolerance not only attracts talent, it creates talent.

Tolerance dovetails directly into another important way of loosening a corporate culture: harnessing the power of cultural diversity.

The notion that working across cultural boundaries can promote creativity is not exactly a new one. In fact, one of China’s great eras of creativity—the Tang Dynasty—was the one era where the nation was most open to foreign cultures. More recently, one can think of Silicon Valley as a cultural melting pot turned job generator: Google founder Sergei Brin, for example, hails from Russia and Tesla’s Elon Musk is a native of South Africa.

The question, though, is: how to practically make diversity pay off in innovation? There are several ways to make that happen.

At the individual level, people could actively try to cultivate culturally diverse social networks. In another study that we conducted at a professional press club in the United States, we found that maintaining a culturally diverse network of professional contacts is particularly helpful when one needs to creatively solve global challenges that require drawing on knowledge and ideas from multiple cultures.8 In the Asian context, what this means is that people should actively try to build and maintain ties with associates and colleagues from diverse countries and cultural backgrounds. This strategy would provide many useful, diverse ideas and resources from around the world, enabling global thinking and creativity.

Drawing on this logic, it is similarly important to cultivate a culturally diverse workplace—but that is just the beginning, not the end. It is also important to hire people with diverse cultural experiences and high cultural intelligence; doing so will make a diverse workplace operate more smoothly, with fewer unproductive cultural tensions. In addition, it’s important to take time and resources to develop employees’ international experiences, perhaps through longer overseas assignments, in order to open their minds and open new markets. These organisational level interventions could help Asian companies innovate not just locally, but also globally.

HARNESSING PRODUCTIVE CONFLICT

Of course, it is possible that a culturally diverse workplace may also lead to more internal dissension—but there are two kinds of conflict. Task conflict refers to disagreement on how to approach and solve the problem at hand. Relational conflict has to do with tensions stemming from interpersonal incompatibilities such as personality clashes. Simple, interpersonal conflict is, of course, unproductive. But a clash of ideas can lead to better ideas. So, in order to change a culture that is too tight, it is important to start embracing productive conflict.

In most Asian countries, however, people tend to dislike and avoid overt conflict and criticism–but conflict and criticism, if done right, can help the creative process. The goal should be to foster what’s called ‘creative abrasion’, where conflicting ideas lead to better solutions.

Creative abrasion worked well, for example, when Apple invented the Macintosh in the 1980s. Steve Jobs famously created the Apple Mac by putting together a team of artists musicians, programmers, zoologists, poets and computer scientists. He separated the group from the corporate offices and told them to invent the world’s most people-friendly computer. They fought it out, and the result changed personal computing forever.

Now, we are not necessarily suggesting that you go out and hire a zoologist to light a creative spark in your company, but there are some more everyday ways of fostering creative abrasion. In the Asian context, where overt conflict is shunned, one approach is to make use of the concept of the devil’s advocate in your decision making, giving a trusted team member the license and responsibility to disagree with the majority.

Another approach is to create a culture where ideas are constructively challenged at every turn, where employees are taught from the start that they’re expected to disagree, and voice that different idea in the back of their mind. And creating that culture requires: (1) recruiting the right people who are not afraid to challenge the status quo, (2) conditioning existing and new employees to debate and challenge each other’s ideas, and (3) implementing the appropriate performance management system that rewards constructive criticism and voicing of dissenting opinions.

LEADING FOR CREATIVITY

Most people are probably familiar with the common classification of leaders into the transactional and the transformational. The transactional leader is the one who tends to put business first, keeps the numbers up and lives in the status quo: think American President Dwight Eisenhower. But the transformational leader changes an institution from the inside out: think American President Abraham Lincoln.

In order to lead for creativity, one approach is to be a transformational leader. Research shows that when leaders lead in a transformational way, employees are more motivated, have greater confidence that they can innovate, and aspire towards change and higher goals. In other words, they’re poised for creativity.

Just as importantly, transformational leadership unleashes the power of dialectical thinking—the willingness to accept change as a fact of life and to tolerate contradiction. Creativity is not about coming up with good ideas out of thin air. More often than not, it is about connecting ideas that were previously not connected. Because dialectical thinkers are comfortable with combining contradictory ideas to address problems, they should have a higher chance of producing creative ideas. However, the power of dialectical thinking needs a potent catalyst: transformational leadership. In an ongoing research project at a large conglomerate in Thailand, the first author and his former graduate student, Fon Wannawiruch, found a positive relationship between dialectical thinking and creativity—but only when employees were given the freedom to think dialectically by a transformational leader.

Interestingly, Asians tend to be more prone to dialectical thinking than westerners, thanks to the influence of eastern concepts such as the yin-yang dynamic of Taoism and the Buddhist precept that everything is temporary and nothing is permanent.9 This is a strength that Asians can harness for creativity. However, Asian leaders, because of their cultural emphasis on power distance and social hierarchy, tend to favour an authoritative approach towards managing employees. This approach is top-down and directive, focusing on compliance rather than changing the status quo. We suggest that to unleash the power of dialectical thinking among Asian employees, Asian leaders should engage in more transformational leadership behaviours. Examples of such behaviours include: (a) setting clear, ambitious, and meaningful goals, (b) intellectually stimulating employees and inspiring them to achieve higher goals besides quarterly key performance indicators, and (c) encouraging them to challenge the status quo.

Conclusion

So maybe it is time we viewed tolerance, diversity, creative abrasion, and transformational leadership as more than just MBA textbook concepts and put them to work in practice. Although we focused on individuals and companies, these principles and approaches can be extended to and applied at the societal or national level. Together, they could well be the secret combination that would one day produce the Asian Henry Ford or the Asian Steve Jobs.