Efforts to promote financial inclusion in Cambodia are paying dividends economically, and unlocking opportunity.

Recently the National Bank of Cambodia, the country’s central bank, hosted the First Mekong Financial Inclusion Forum in conjunction with several development partners. The Forum was aimed at strengthening the level of cooperation and knowledge exchange between countries and institutions in a drive towards financial inclusion within the Greater Mekong Subregion.

Prior to the Forum, I had the opportunity to meet with Serey Chea, Director General of the National Bank of Cambodia, to discuss the country’s efforts to achieve greater financial inclusion, and learn about its expanding microfinance sector.

Cambodia has begun to attract international attention for its economic successes, especially its economic growth. It is one of the fastest growing among post-conflict societies, and is likely to graduate to the middle-income developing group of countries within the next decade. In the meantime, the International Monetary Fund, in July 2016, recorded Cambodia’s transformation to lower-middle-income country status, noting Cambodia’s sharply increasing integration with the global economy and the significant fall in poverty.1

The garment sector, together with construction and services, is the main driver of the economy. Growth is expected to remain strong in 2016, as recovering internal demand and dynamic garment exports offset stagnation in agriculture and softer growth in tourism.2 Although real growth is estimated to have slowed to 7 percent in 2015 from 7.1 percent in 2014, Cambodia continues to record significant sustainable economic growth through the opening up of the market and ultimately, poverty reduction.3 By the end of 2015, private sector credit growth in the Kingdom averaged nearly 30 percent (year-on-year) over the past three years and the credit-to-GDP ratio doubled to 62 percent, higher than the median Emerging Markets’ level and about twice the median Low Income Countries’ level.4

However development has also been uneven, reflecting the stubborn problems of a developing economy. There is an increasingly unequal distribution of wealth (both geographically and socially), limited financial inclusion, a wide gap in development between urban and rural areas, along with significant social issues such as gender and poverty concerns. The ability to improve access to finance remains essential. Yet the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), for example, which generate most of Cambodia’s economic output and employment, still have difficulty accessing finance at an affordable cost, which hinders their competitiveness and capacity to develop. The plight of the ‘unbanked’, who have no access to mainstream finance, leaves vulnerable groups open to exploitation by unscrupulous interests. An overriding consideration here is financial literacy, whether for small businesses or the unbanked, as it provides both groups with the knowledge needed to unlock access on many levels, from opening bank accounts to the running of a family-owned enterprise.

Policies introduced by the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC), the country’s central bank, are intended to meet these challenges, including regulatory challenges. It encourages and maintains financial system stability and development through the promotion of financial inclusion, oversight of the payments system and regulation of the banking system.

One key policy initiative involves an emphasis on financial inclusion through microfinance, while others are aimed at financial literacy and increasing the levels of what is called ‘bankability’. Often described as “the key to breaking the poverty cycle” through access to affordable finance, microfinance supports the theory of economic development that argues that people can be moved out of poverty through empowerment as business owners. Its significance has been recognised by the United Nations, which declared the year 2005 as the Year of Microcredit, as well as by Cambodia itself, which declared 2006 to be the Year of Microfinance.

Reflecting Cambodia’s move from a ‘planning economy’ to a ‘free market’ economy in 1991, following the Paris Accord, the country’s central bank steers a middle course when it comes to a financial inclusion model. “We aim for a hybrid model,” says Chea. “We don’t seek heavy regulation as in South Africa, but we also shy away from unregulated environments.”

A major element of financial inclusion is the emphasis on access at an affordable cost, or price, a point not lost on Chea. “People don’t usually pay attention to ‘affordable cost’”, she tells me. “Many just try to push financial services to everyone without considering the price that people have to pay for it.” Yet closing the accessibility gap with affordable prices is central to ensuring financial inclusiveness. In fact, there are those who would argue that as banking services are in the nature of a public good, the availability of banking and payment services to the entire population without discrimination is a key objective of financial inclusion.

Financial inclusion

The delivery of financial services at an affordable cost to sections of disadvantaged and low-income segments of society, or financial inclusion, is an integral part of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Globally, an estimated two billion working-age adults have no access to the types of formal financial services delivered by regulated financial institutions. This sees them mired in poverty traps and vulnerable to myriad social issues, including extortionate forms of money lending, from which there is no way out except for the concerted effort of all nations to achieve the SDGs.

Current figures on formal financial inclusion in Cambodia show an inclusion rate of 59 percent, with 29 percent of adults considered financially excluded.5 Financial inclusion is higher amongst females at 73 percent, compared to males (69 percent) and is higher in urban areas (74 percent) than rural areas (69 percent). Microfinance institutions are commonly used (24 percent) as opposed to banks (17 percent).

The NBC is now in the process of preparing and rolling out a national strategy on financial inclusion in conjunction with the United Nations Conference on Financing for Development, which should make it easier to access finance.

Microfinance as a key driver of financial inclusion

The promotion of access to finance, or financial inclusion, for low income groups is usually associated with microfinance, says Chea. She refers to the ground breaking work of Grameen Bank founder, Muhammad Yunus, the social entrepreneur and Nobel Peace Prize recipient known for his pioneering work with loans to entrepreneurs who are too poor to qualify for traditional bank loans.

Credit is the primary financial product offered by most microfinance institutions (MFI) to small businesses and individuals. In Cambodia, MFIs provide financial and non-financial products and services to satisfy clients’ needs, including group and individual micro loans, micro savings, money transfers and micro insurance.

Approximately 80 percent of Cambodia’s MFI clients live in rural areas, of which 81 percent are women. However determining and maintaining affordable rates remain challenging. “In the main, microfinance services are still expensive compared to bank services because many of the institutions are labour intensive, operating in remote areas with high overheads. This requires spending on human resources who will have to go into the field to understand the whole business situation, as well as collect the money,” says Chea.

The country’s microfinance sector has proven attractive to foreign investors, especially those with social missions in mind. The financial inclusion imperative has attracted the support of many institutions in the Mekong region. One of these is the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI). Founded in 2008 by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the AFI has 123 members from 95 countries and is a valuable forum for the region’s central banks and microfinance banks. The NBC recently became its 99th principal member.

The successes have gained recognition. Cambodian MFIs won three out of the five Financial Transparency Awards offered in 2005 by the worldwide Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, which considered 330 institutions from 62 countries for these awards. In 2006, four Cambodian MFIs received Financial Transparency Awards.

Microfinance and central bank policy

The microfinance sector constitutes about 20 percent of Cambodia’s whole financial system, which has led the central bank to view it more seriously than it used to, especially in terms of its impact on financial stability. However, Chea explains that the role of central banks in microfinance can be problematic. The generally accepted view is that central banks should look after financial stability rather than the supervision and regulation of microfinance. Failure on the part of institutions in that area would have limited impact on financial stability, so the theory goes, and it is therefore unnecessary to spend much in the way of resources on them.

However the Cambodian perspective differs. “Our definition of financial stability”, Chea says, “boils down to how much it is going to impact the society as a whole versus just the financial system. You might debate that definition of financial stability, but if there’s disruption in the financial system, then you call it financial instability. For us, even though the failure of microfinance wouldn’t necessarily have much impact on the functioning of the financial system, the number of people that the MFIs are serving is huge in Cambodia. The customer base is so big, that even if a failure doesn’t create financial instability, it can create social instability. That’s something we take seriously.” Ultimately, therefore, the need for regulation comes down to the fact that lending to low income consumers is perceived as risky for the MFIs as well as for the investors of these institutions, especially as several of the early MFIs in Cambodia began as small organisations, and some were NGOs, with limited governance.

‘Bankability’

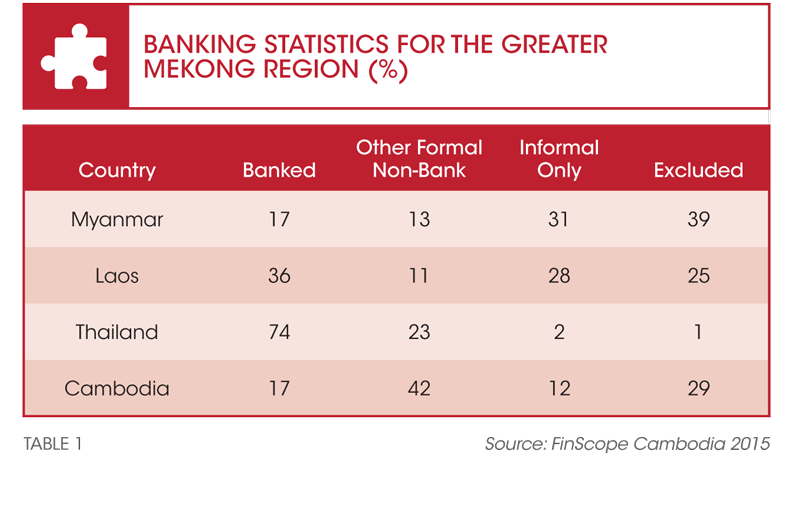

The conventional banking system is aimed at ‘bankable people’—individuals with bank accounts and good credit records who will prove acceptable to institutional lenders. However it presupposes access to and participation in the mainstream financial system using a bank account—and the marginalised or low income groups are unlikely to meet either requirement. Table 1 provides a comparison of financial inclusiveness across the Greater Mekong Subregion.

One of the first steps towards financial inclusion is possession of a bank account and Cambodia’s central bank aims to see 80 percent of Cambodians with bank accounts by 2020. Globally, there has been a significant drop in the number of ‘unbanked’ individuals, falling by 20 percent in 2015. A World Bank report noted that from 2011 to 2014, 700 million people became account holders at banks, other financial institutions, or mobile money service providers.6

Financial literacy

Financial literacy also has implications for the wider community, that is, beyond just benefitting the marginalised. Microfinance is now such a major player in the Cambodian finance sector that there are very real concerns that many people will not understand the terms and conditions connected with financing transactions, i.e. credit and loans. The Cambodian central bank believes literacy programmes are best carried out through the formal education system. And that, Chea says, will need cooperation from the Ministry of Education.

The central bank’s recent Consumer Financial Capability Development campaign is aimed at teaching the public how to use financial services effectively. The programme is free and features catchy video clips urging people to save for the proverbial ‘rainy day’ and manage their finances wisely; along with public service announcements for radio distribution, and a range of printed collateral such as postcards and banners. Campaign ambassadors are used to help spread the word.

Chea outlines key features of the programme, “Basically, it is designed to help the public understand their rights and responsibilities; that loans should be used wisely and are able to generate profits to service debts and repayments, and that borrowing should not be irresponsible or reckless. A key element is to educate the public on their choices, the right to negotiate, and the right to communicate should they have any doubts about any aspect of a financial transaction. If they are offered one rate, they don’t have to accept it. They can walk out and see if a better rate is on offer.”

By and large, people need to learn to communicate, not only with the service providers, but also the relevant authorities, she adds. “They shouldn’t just keep quiet. Our challenge is to make people understand that this is their right to ask, and it’s also the responsibility of the institution to answer them.”

This is particularly true for those from rural areas, she points out. “They’re usually intimidated by people in the big urban areas and will generally not dare to ask too many questions.”

Regulating the sector

Balanced regulation from the central bank is a key strategy. The Europe- based investment funds, development banks, and others, considered that if the MFIs were regulated by the central bank, then they would be required to file and publish audited financial reports. Chea commented, “We were among the first countries in the world to regulate microfinance. Where other countries feel that they’re too small to regulate, or that it’s a waste of resources, we’re taking the approach that we should do it, despite a lot of criticism about our approach.”

The formation of a credit bureau and plans to introduce a Khmer-score—which relates to the creditworthiness of a person—add strength. Similar to the FICO score in the United States, the proposed Khmer-Score assesses the likelihood that a person will pay his or her debts. This will help microfinance outlets better identify their client, while enabling greater bargaining power on the part of the client if he or she is of good credit standing.

The credit bureau is a recent innovation. Chea, who also chairs the bureau, explains that, in common with its counterparts elsewhere, the bureau identifies the people and their credit histories to enable lenders (MFIs) to better assess their client. But, she adds, “If someone has a very good report showing that they pay everything on time, they should be able to use it as an asset, and be able to bargain for a cheaper loan.”

The new bureau is also one of the first in the world to include two finance sectors (banking and microfinance) under one roof, which enables the same product to be sold to two different sectors. Making sure the internal price structure of the product is fair to all has been a challenge. “However it’s made us one of the best in the world,” said Chea.

Most of the necessary regulations are in place, although the central bank has yet to introduce an e-commerce law to protect consumers and buyers. The 1999 Law on Banking and Financial Institutions clearly defines the legal status of MFIs as a provider of loans and deposits to poor and low income households and micro-enterprises, and requires them to ensure minimum capital and governance systems are in place, and then goes on to supervise and regulate them using prudential principles on capital guarantees, reserve requirements, and more. Regular off-site supervision and inspections are carried out to monitor compliance with prudential banking principles as well as promote investor and public confidence in the rural finance industry.

Hurdles and high points

The countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion are gradually shifting from subsistence farming to more diversified economies, and on to more open, market-based systems. The move has been a contributing factor in Cambodia’s improving status in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index for 2016, a high point in a country’s quest for investment. In 2016, Cambodia rose to 127th place out of 189, up from 133 in 2015. By comparison, neighbouring Myanmar ranked 167 on the index, and Lao PDR 134.

One unique challenge on the horizon will be the empowerment of women entrepreneurs through financial inclusion, though women already comprise 80 percent of borrowers in Cambodia’s microfinance sector. Cambodia’s small businesses, like many in the region, commence with the woman in the family. “They’re the ones who go out and borrow money, who manage the finances and operate the business,” says Chea, of enterprises she terms ‘survival businesses’. However as the economy continues to diversify and grow, these survival businesses will likely transition to more profit-focused enterprises. A different set of skills will be needed, beyond making sure income covers expenses. Financial literacy programmes that go beyond the basics of smart saving will be a first step in this direction.

Technology is another. Everyone acknowledges that technology will be able to make financial services cheaper, which is particularly relevant for the microfinance sector where technology will be a big game changer. However Chea points to the language barrier. “Technology tends to be in English but that’s not a language most people speak or understand.” Nevertheless, language barriers have not held back other non-English speaking innovators in other parts of the world. And as experiences in countries such as China have shown, a combination of home-grown disruptive innovation and technology can, should, and will, continue to play an important role in advancing a country’s preparedness to face challenges in whatever form. Cambodia will likely be no exception.