ASEAN has been enjoying solid growth rates over the last few decades. Since 1980, growth has averaged 5.4 percent, well above the global average of 3.4 percent over the same time period. Growth in ASEAN has also been faster than other emerging regions—Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa—since 1980. This growth outperformance has seen the gap between global GDP per capita and ASEAN GDP per capita more than halve, dropping from 6.0 times in 1980 to 2.7 times in 2013.

Strong fundamentals sustain growth

From 1980 to 2013, ASEAN’s annual GDP growth was generally above 5 percent; the exceptions were the Asian Financial Crisis and the Global Financial Crisis. Growth during 1990 to 1994 was particularly strong. On hindsight, however, investments were possibly over-stretched, and the high growth rates were undermined by under-developed foreign exchange mechanisms and weak external balances. Subsequently, 1995 to 1999 was possibly the worst period for ASEAN in recent history as the Asian Financial Crisis took place and growth plummeted to an average of 3.5 percent. But since bottoming out in 1998, growth has rebounded and governments have taken the bitter pill and pushed through much needed reforms. Consequently, for the period 2000-2004, GDP growth averaged 5.1 percent, and 4.9 percent between 2005 and 2009.

Even during the Global Financial Crisis, ASEAN growth remained a step ahead of the rest of the world. ASEAN GDP growth was 4.7 percent between 2008 and 2010. This is impressive given that the region is export-driven. But exports to a pump-priming China, as well as growing domestic engines, particularly through consumption and investments, buffered ASEAN growth to some extent. From 2010 to 2013, growth strengthened to an average of 5.9 percent, although the figure may be biased upwards due to the significant rebound post crisis. Still, excluding that 2010 bounce, GDP growth averaged 5.3 percent from 2011 to 2013 (refer to Figure 1).

Low urbanisation provides room to grow

Despite the high growth the region has enjoyed over the last few decades, we believe ASEAN has considerable room for easy growth in the future. ASEAN is still relatively rural. As of 2013, ASEAN’s urban population was only about 47 percent, while the world had crossed the 50 percent urbanisation mark back in 2007. Within ASEAN, only Singapore, Brunei and Malaysia are considered urbanised. If we assume that the urbanisation trend in ASEAN continues along its recent path, we estimate that GDP per capita in the region will more than double to US$8,500 in 2030 from US$3,900 in 2013. By then, 60 percent of the region could be urbanised.

There are many similarities between China in the past decades, and ASEAN today. The most important is perhaps ASEAN’s acceptance of economic openness being a key requisite for growth.

|

LESSONS FROM CHINA GROWTH THROUGH TRADE LIBERALISATION China’s extraordinary economic development owes much to its active participation in global trade. By 2013, it was the world’s largest exporter and second largest importer. Trade has helped China to improve the efficiency of resource allocation, ensure a supply of natural resources for domestic consumption, and gain from the transfer of technological know-how through imports of capital goods. Trade growth has also contributed strongly to the creation of non-farm jobs, and reduced rural poverty. China’s experience demonstrates the importance of global trade in facilitating improvements in economic structure and propelling growth. While many factors have contributed to China’s outperformance in global trade, one of the most important, in our view, is the country’s strong adherence to economic openness policies. This can be seen in the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Shenzhen and other similar regions as early as the 1980s. These were designed as areas where foreign companies (and later, domestic firms) could invest, and take advantage of lower taxes, limited trade controls, and enjoy a supportive bureaucracy. The SEZs were focused on attracting firms that would manufacture for export, although as the economy developed, many firms established in these zones turned to the domestic market. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 expedited its integration into the world economy. The average tariff rate dropped from 43 percent in 1992 to less than 10 percent by 2008, according to the WTO. Between 2003 and 2008, China’s foreign trade grew at a record average rate of 26 percent. China also made strong commitments to liberalise services trade in the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services. From China’s perspective, the accession to the WTO meant much more than just securing access to the world market, as it also allowed China to implement reforms according to a more transparent and rule-based global system. There are many similarities between China’s past several decades and ASEAN today. The most important is perhaps ASEAN’s acceptance of economic openness being a key requisite for growth. The region actively participates in trade negotiations and attempts to attract global companies for investments. Tax incentives are typically used to attract investments. The push to integrate partly stems from the positive impetus of being able to better attract investments as a region than as separate economies. The market may be smaller than China, but growing wealth will help to bridge some of the gap. Tariff rates within the region will be synchronised further over the next few years and that will help boost intra-regional trade. Parts of ASEAN will continue to provide a cost-competitive and abundant labour supply for manufacturers looking for a more viable option outside of China. The region’s demographic profile also remains favourable compared to China. |

ASEAN-China trade serves as an engine of growth

ASEAN is already one of the world’s top exporters. The ASEAN-China trade corridor alone accounted for US$491 billion in 2013, and has grown seven times since 2000. ASEAN is poised to benefit from the shift of low value-add manufacturing out of China. Today, ASEAN is the fourth largest exporter in the world after China, the U.S. and Germany. In 2013, ASEAN accounted for 7 percent of global exports, a share held steady since 2000, even as China rose to become the largest exporter in the world. Assuming 15 percent of China’s exports (which are considered low value add) are produced out of ASEAN, the region will become the second largest exporter in the world.

Intra-ASEAN trade is also receiving strong investor interest. Currently, around 26 percent of the region’s total trade is amongst member states. Closer regional cooperation will likely further raise the intra-regional trade volume.

The ASEAN-China trade corridor is one of the main trade corridors. In 2013, this trade was worth US$491 billion, 7 times that of 2000.

An investment magnet

THE NEW LOW-COST DESTINATION

ASEAN’s attractiveness is not lost on foreign investors. In fact, ASEAN overtook China for the first time in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2013. Following the development of the original four Asian dragons—Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore—investment was anticipated to shift to the four tigers—Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. However, the onset of the 2008 Asian Financial Crisis and the opening up of China tempered such expectations. But with China having developed furiously over the last two to three decades and losing its cost competitiveness in the process, the investment focus is now back on ASEAN. With the right policies, ASEAN can stand to benefit greatly from China’s higher-cost environment.

Mekong (referring to Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam here), in particular, provides an attractive option for manufacturers who are searching for new production bases. Mekong’s young and abundant labour force and relatively low operation costs attract global manufacturers, particularly those in labour-intensive industries. As an estimate, a Chinese worker in the manufacturing sector in the Pearl River Delta earns around US$700 per month, while in Myanmar, a comparable worker may only draw US$110 per month.

OPEN DOOR APPROACH

One of the key characteristics of a successful economy is that the country is typically open to foreign investments. This point is not lost on ASEAN policy makers. ASEAN countries have courted FDI by improving the ease of conducting business in their markets, increasing infrastructure investments and providing various investment incentives. Since the Asian Financial Crisis, ASEAN has come a long way and the increase in FDI is reflective of the improvement in the business and investment environment.

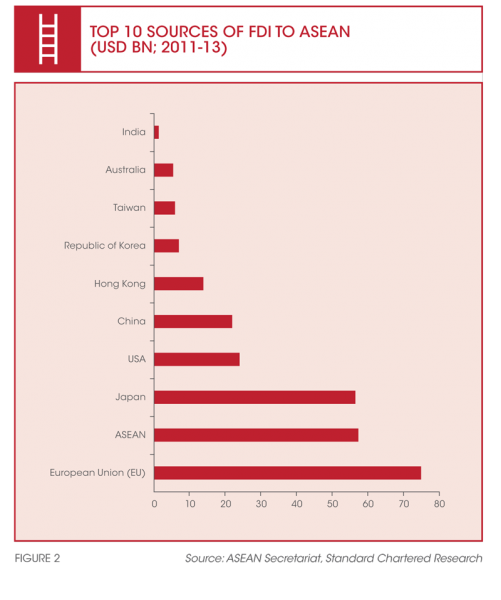

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development data, FDI into ASEAN rose 7 percent to US$125 billion in 2013. The region attracted nearly 9 percent of global FDI, a significant increase from 4.1 percent in 2005. While East Asia still draws in the bulk of the FDI coming into Asia, ASEAN’s share is increasing rapidly. In 2013, ASEAN attracted nearly 30 percent of total FDI into Asia, up from 19 percent in 2005. Japan is the third-largest source of FDI to ASEAN. It has invested more into ASEAN than into China in recent years, likely owing to geopolitical tensions and China’s diminishing cost competitiveness (refer to Figure 2). In 2013, ASEAN attracted more FDI than China, albeit by a marginal US$2 billion.

A FOCUS ON MANUFACTURING

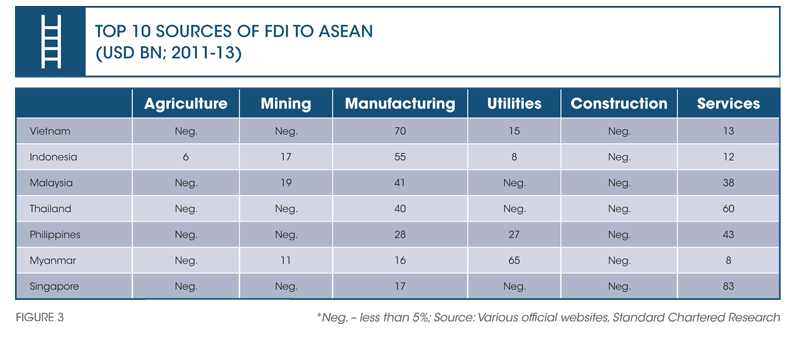

A dominant portion of FDI into ASEAN goes into the manufacturing sector. This reflects the positive attributes ASEAN provides for investments in manufacturing facilities. Manufacturing tops the list for Vietnam, where we have seen significant investments in the electronics sector. The ability to compartmentalise the manufacturing process in the electronics sector allows companies to source from the most cost-competitive location for their operations. In that respect, Vietnam provides an attractive avenue for companies looking for more competitive cost options. Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand also receive a large amount of investments in their manufacturing sector. Myanmar receives investment looking to tap its mining and power sectors. For Singapore, the bulk of the FDI is received in the financial sector (refer to Figure 3).

DEMOGRAPHICS

ASEAN also has an edge in terms of demographics relative to China. As of 2013, ASEAN’s median age was about 27 years old—much younger than that of China, which was estimated at 32 years. ASEAN will also continue to add to the labour force over the next few decades. Compared to 2010, ASEAN’s labour force is expected to grow by about 70 million by 2030, while China’s labour force is expected to contract by almost 70 million. Indonesia and the Philippines are among those poised to reap the benefits of this demographic dividend, and will achieve faster and more resilient growth. This, combined with the low levels of household debt, rising urbanisation and potential increase in productivity in the workforce, will position these countries to become key economic powerhouses in the region in the coming few decades. At the less favourable end, the median age of Thailand and Singapore is forecast to be over 45 by 2045. In fact, Thailand’s labour force is expected to shrink by almost 5 million between 2010 and 2030.

ASEAN’s consumer market: awakening the giant

The ASEAN region is not just attracting investment because of its production capacity. Investors also perceive it as a huge market. Indeed, looking at ASEAN as a single country, it would be the third largest market in the world after China and India, with a population of 620 million. Indonesia is the largest country with about 250 million people. The Mekong region also provides a large market for investors. The total population of Mekong is around 170 million, with 90 million in Vietnam. Importantly, Myanmar has about 60 million people with the market largely untapped, providing a very attractive option for invest or seeking a first-mover advantage.

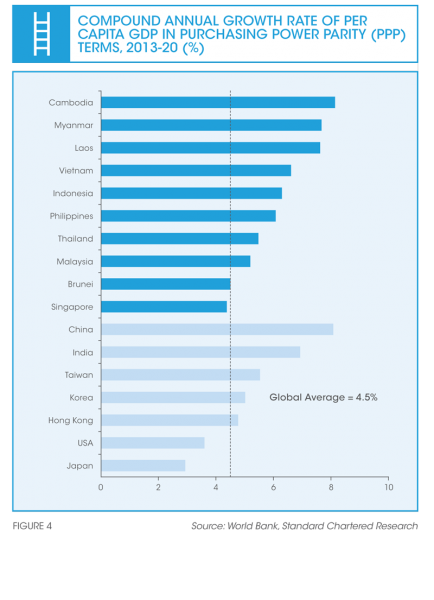

Low labour and operating costs are cited as the top reasons why companies move their operations to Mekong. The large domestic market is another key reason—although income levels are low currently, the local populace is becoming wealthy at a fast pace. For example, in a recent questionnaire we conducted, companies in Vietnam expected average wages to rise 5 to 10 percent in 2014, even though the local economy’s performance is currently lacklustre. The Mekong Delta economies have experienced the fastest rise in GDP per capita from 2000 to 2013 (refer to Figure 4).

The Mekong Delta economies have experienced the fastest rise in GDP per capita from 2000 to 2013.

We see tremendous growth potential for the ASEAN consumer market, owing to rising urbanisation and income growth. The anticipated shift in labour structure and demographics is expected to create significant new demand. It is also expected to cause a shift in consumption patterns as ASEAN consumers allocate larger shares of spending to high-quality products and services. We believe demand in Indonesia, Vietnam and Myanmar will see explosive growth, given their relatively large population sizes as well as low penetration rates for consumer durables and services. Yet there are potential challenges. Despite cultural similarities with China, the region’s diversity suggests that companies looking to tap its strong growth potential will need to develop multi-pronged strategies in order to cater to different cultures, tastes and preferences. Furthermore, local governments may introduce trade barriers for strategic industries in the absence of strong domestic players. Nonetheless, this should not undermine the vast potential opportunity offered by the ASEAN consumer market.

Indeed, looking at ASEAN as a single country, it would be the third largest market in the world after China and India with a population of 620 million.

But there is work to be done

INFRASTRUCTURE

ASEAN economies need infrastructure development to shift investment from China and rival neighbours such as India. ASEAN economies are relatively advanced in telecommunications and have good access to electricity. But improvements are needed in transport infrastructure. Furthermore, a regional transport infrastructure across ASEAN is needed to integrate the region more closely in the longer term. There is some reason for optimism on this front. Indonesia’s new president is trying to allocate more funds to build the country’s infrastructure. Thailand’s new government is trying to push ahead with an ambitious THB 2 trillion (equivalent of US$61.2 billion) infrastructure spend over the next seven years. According to the Global Logistics Performance Index, ASEAN’s infrastructure score improved across the board between 2007 and 2014. With the exception of Indonesia (whose global infrastructure rank dropped from 45 in 2007 to 56 in 2014) and Singapore (stable at number 2 globally), all other ASEAN economies moved up in the global infrastructure ranking. Vietnam, for instance, moved up 16 spots to rank 44.

But China ranks higher than all ASEAN member states except Singapore and Malaysia in terms of its economic competitiveness and infrastructure. ASEAN member states will need to improve on both counts to attract more investment into the region. That said, China’s infrastructure was also weak 30 years ago, but this did not stop investors from seeking to take advantage of its low-cost environment. However, the lack of infrastructural development will ultimately limit the overall amount of investments a country can attract, as a business will take into account all costs on a holistic basis.

PRODUCTIVITY

ASEAN has experienced positive, consistent and constructive productivity growth over the past decade, particularly on reforms after the Asian Financial Crisis. However, most of ASEAN reports productivity levels about a third to half of those in the U.S., and are comparable to that of China. The exception is Singapore, whose productivity levels lead the rest of Asia. Outside of Singapore, Malaysia leads the rest of the region in terms of productivity and income levels, with government policy aimed at moving the economy towards high income status by the end of this decade. The Philippines lags in the region.

Given that most of ASEAN is at a relatively early stage of development, productivity growth requires supportive input from capital and labour force growth. ASEAN can partially bridge the productivity gap between the region and more productive economies such as Japan and Australia simply by increasing the quantity and quality of capital stock per worker. This requires investments in productive capital stock such as transport equipment, machinery, roads and factories that enhance productivity (versus investment in residential property). We estimate that the capital stock per worker in some ASEAN countries, such as the Philippines and Indonesia, is about one-fifth that of U.S. workers. ASEAN also needs to enhance training and human capital development to benefit from a higher quality of labour.

ASEAN is pro-growth

ASEAN’s attractive attributes include its cost-efficient labour supply, trade pacts, supportive investment policies, regional stability, growing wealth and rapid economic growth. The region enjoys pragmatic growth policies and relatively stable political environment. ASEAN governments are focused on growth. They are keen to improve infrastructure and are generally supportive of foreign investment. The region also actively pursues trade negotiations. As of 2013, ASEAN has been involved in negotiating 90 Free Trade Agreements (FTA), of which 40 have been signed. The region is also currently involved in two large multilateral FTAs, namely the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and TransPacific Partnership.

The formation of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015 brings even more reason for confidence that the region will be able to sustain its high growth rate over the medium-term. The initiative aims to push for a single market and production base in ASEAN, create a competitive economic region, and facilitate equitable economic development in the region. ASEAN works by consensus—both a strength and weakness. Most ASEAN countries are focused more on domestic development than regional development. But with competition for global opportunities becoming more challenging, ASEAN needs to integrate better as a region to face off challenges and attract investors. As an economically unified region, ASEAN will also have a more effective voice on the global stage.