How Starbucks faces the emergence of ‘new retail’, or the seamless integration of offline and online retail.

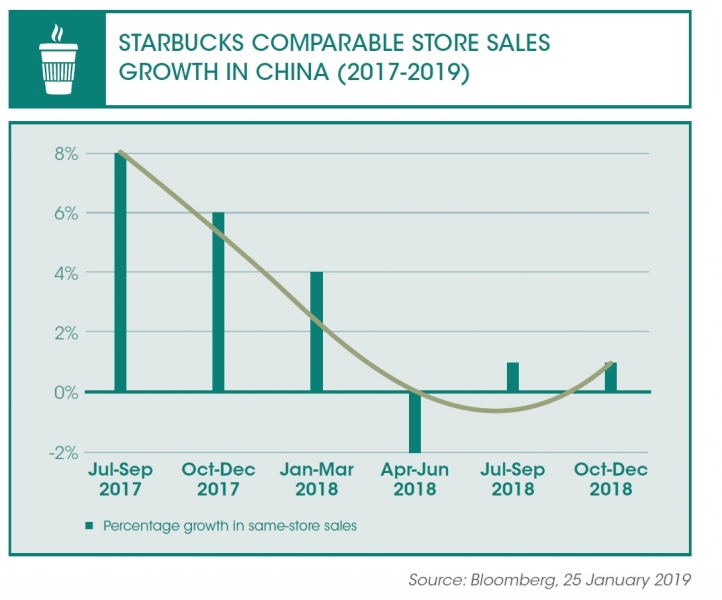

In 2018, Starbucks was the undisputed leader among China’s coffeehouse chains, with more than 70 percent in market share and 3,600 cafés. The brand’s success was rooted in its core proposition of providing consumers a ‘third place’ (also called di san kong jian in Mandarin)—an escape from both home and the workplace—to relax and indulge themselves. Starbucks had entered China in 1999, and the country (and Asia Pacific overall) was the company’s fastest growing market. It was hence quite surprising when the company faced a setback in the region in 2018, witnessing a decline in its third quarter sales, total number of transactions for the year, and annual operating income.

Starbucks’ sudden downturn in the region was attributed to the threat posed by Luckin Coffee to its ‘third place’ positioning. Launched in China in November 2017, Luckin grew to more than 2,300 stores in just 17 months. Unlike Starbucks, it offered lower prices and the convenience of having coffee anywhere—at home, the workplace or a café. According to the company, its mobile app-linked order and cashless payment platform, along with a store pick-up and delivery model, appealed to the country’s digitally savvy millennials. Over 2018-2019, the company successfully raised US$550 million, and in May 2019, launched its initial public offering. By the end of 2019, Luckin aimed to open a total of 4,850 stores in China to surpass Starbucks’ planned network of 4,200 stores.

The sudden rise of Luckin raises important questions for Starbucks. What does it need to do in order to maintain its dominance in China? Should it emulate Luckin and work towards building a stronger and wider delivery channel, or should it continue to pursue its premium priced experiential retail strategy?

'Third place’ positioning: Home, work and Starbucks

By the end of 2018, Starbucks, which was founded in 1971 in the U.S., was by far the largest coffeehouse chain in the world with total revenue of US$24.7 billion, 29,324 stores across 78 countries, and a global headcount of over 291,000 employees worldwide.1 In fact, Starbucks had more than 11 times the revenue and seven times the number of outlets of its closest competitor, Costa Coffee.

From the outset, Starbucks provided consumers a differentiated and unique experience of coffee consumption, which it called the ‘Starbucks Experience’. Its outlets were developed around the concept of a ‘third place’, where people could pamper themselves, socialise and enjoy spending time there. This not only clicked well with customers who did not mind paying more for their coffee to enjoy the experience, but also earned Starbucks a distinct identity in the increasingly competitive café industry. Another factor that contributed to Starbucks’ impressive growth trajectory was its adherence to rigorous standards of quality and a suitably adapted food menu that catered to local tastes.

Over 2000-2008, Starbucks’ outlets across the globe grew more than threefold, from 5,000 to 16,680. However, in this quest for expansion, inadvertently, there was a greater thrust on ‘takeaway’ than the company’s original value proposition of consumers sitting in the café and enjoying their coffee.2 Consequently, Starbucks’ sales growth over this period declined, and there was a drop of 42 percent in its stock value.

REBUILDING THE STARBUCKS EXPERIENCE

Rebuilding the ‘third place’ equity helped turn around the company. In 2008, besides closing down 600 stores (many of which had been opened in the previous three years), Starbucks trained its baristas to improve their art of brewing coffee, bought more advanced coffee equipment, and reorganised its supply chain for better inventory management at the cafés. Starbucks also integrated technology to provide consumers a seamless digital experience, improved its social media presence, and introduced customer rewards cards. In order to ‘recapture the coffeehouse feel’, it redesigned its stores in terms of colour scheme, architecture, lighting, and furniture.4

In 2014, Starbucks changed its no-advertising policy and launched its first ever global brand campaign, ‘Meet me at Starbucks’. The campaign, shot in 59 stores located across 28 countries, strongly emphasised the relationships customers cultivated when meeting at Starbucks. In 2016, 2017 and 2018, the coffeehouse chain spent US$248.6 million, US$282.6 million and US$260.3 million respectively, on advertising.

UPSCALING THE EXPERIENCE: PREMIUM STORES

In 2018, Starbucks launched its ultra-premium roastery and reserve project.5 Reserve roasteries were essentially coffee emporiums (part café and part production facilities), and the reserve stores were a café-only version. While a traditional Starbucks store averaged 1,800 square feet in floor space, the reserve roasteries were 10 to 15 times larger. It provided an immersive retail experience including Italian artisanal high-end food by Princi bakery, lounge areas with fireplaces, and a full liquor bar, in addition to a traditional coffee bar showcasing its innovative specialty—its premium brand, small-lot Starbucks reserve coffee. By the end of the year, Starbucks had opened four reserve roasteries in Seattle, Milan, Shanghai and New York,6 and it planned to open another 30 reserve roastery emporiums and 1,000 reserve stores over the next few years, with the primary objective of amplifying the brand-customer experience.

Starbucks: Caffeinating China

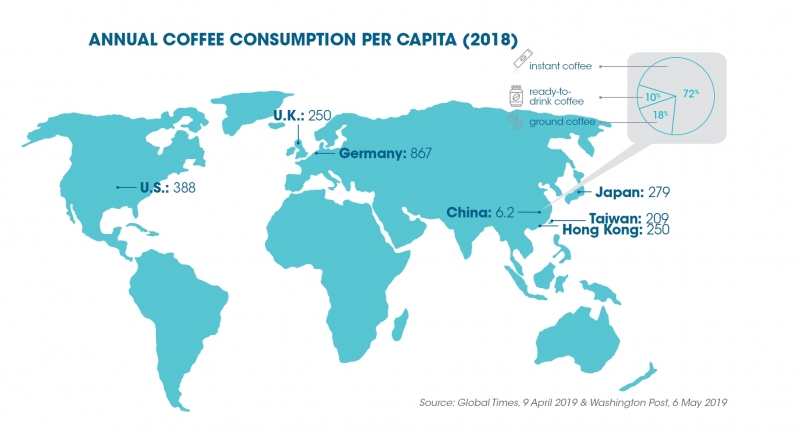

In 2018, China’s annual coffee consumption per capita was only 6.2 cups against 209 in Taiwan, 250 in the U.K. and Hong Kong, 279 in Japan, 388 in the U.S., and 867 in Germany. However, the annual average coffee consumption in the country, a largely tea-drinking nation, had grown at 15-20 percent over the last decade compared to the global average of only 2 percent.

China’s increasingly affluent consumer class had greater awareness of Western trends, and associated coffee with a modern lifestyle and status. Of the three consumer coffee categories—instant coffee (72 percent in market share), ready-to-drink coffee (10 percent) and fresh ground coffee (18 percent), the demand for fresh ground coffee, despite being the most expensive, was increasing with the rising trend of on-premises consumption in the country.

The coffee culture in China had, to a large extent, been ushered in by the entry of Starbucks in 1999. By 2018, the coffeehouse chain had expanded rapidly across more than 150 cities, opening on average, one new store every 15 hours between 2013 and 2018. By 2016, Starbucks was the undisputed leader with a market share of 74.6 percent, far ahead of its closest competitors McCafé at 9.1 percent, Costa Coffee at 8.4 percent and Pacific Coffee at 3.9 percent.7 In Shanghai alone, Starbucks had about 600 stores, the largest number of outlets in any single city in the world.

A PREMIER DI SAN KONG JIAN

Starbucks’ ‘third place’ positioning struck a chord with the consumers struggling to cope with increasingly crowded living and work spaces, and congested traffic conditions in Chinese cities. The coffeehouse chain was an attractive alternative for people to get together conveniently and comfortably. Its Western upscale sensibility presented an aspirational but affordable luxury to a growing middle class looking to indulge itself.

In 2011, the company’s loyalty programme, ‘My Starbucks Rewards’, was introduced in China, and more than seven million members had signed up by 2018.8 To make the brand a little more exclusive, consumers in China were required to pay to join the programme, unlike in the U.S. where it was free. In 2014, the coffeehouse chain also introduced a stored value card to provide customers with a potential gift item besides a convenient payment method.

To position itself as a premium coffee brand, Starbucks priced its coffee higher than that of the local players in China, and selected high-end locations for its stores such as luxury malls and iconic office buildings. Additionally, since Chinese society associated foreign brands with a higher status, the coffeehouse chain often labelled its imported products with the country from which they had been sourced.9 It introduced most of its global brands in China, and offered menu choices similar to what it served in the U.S., while introducing differences such as red bean flavoured scones to appeal to the local palate.

The introduction of 30 Starbucks reserve stores in the country and the world’s largest Starbucks reserve roastery in Shanghai in 2017 further aimed to build on its upscale image and encourage consumers to linger over their expensive brews.

ACCESSIBLE AND LOCALISED

Targeting white-collar office workers, Starbucks located the majority of its retail stores in the central business district of Chinese cities. To encourage the congregation of formal and informal groups of co-workers, friends or family, it designed its stores in China to be up to 40 percent bigger than those in the U.S., with an open-style sitting area that had no interior walls and spilled out onto walkways and lobbies.10 Many of its stores were adorned with locally-crafted wine urns and wooden carvings to reflect Chinese heritage. In 2018, Starbucks established its first Asian R&D centre in China to develop a more locally-inspired coffee menu.11

GOING DIGITAL

Starbucks also undertook a number of steps to cater to China’s highly digitised customers and an increasingly cashless society. Through its mobile app, the company allowed ‘My Starbucks Rewards’ members to manage their card balance, and also made it easier for them to earn and redeem rewards, and find a nearby Starbucks store with the store locator feature. In early 2016, it launched a mobile payment feature on its app, enabling its members to e-pay for their purchases at stores nationwide.12 The coffeehouse chain also partnered with WeChat Pay in December 2016, and followed up with a tie-up with Alipay in 2017—the two portals together held a 90 percent share of China’s mobile payments market.13 By 2018, almost 80 percent of Starbucks transactions in China were cash-free.14

Given the high penetration level of digital communication in China, the coffee chain promoted itself using local social media platforms. In 2017, it launched its campaign, ‘Say it with Starbucks’, which enabled about 826 million WeChat users to buy a beverage or a gift card through the app.15

Luckin Coffee: The home-grown caffeinated foe

While the coffeehouse culture in China had come a long way since the entry of Starbucks, it was in the throes of yet another transformation with the emergence of ‘new retail’, a term referring to the seamless integration of offline and online retail. In China’s coffee industry, new retail was primarily led by three key factors—a rapidly growing coffee-drinking population, a high level of mobile and digital penetration, and most importantly, an increasing demand for delivery by convenience-oriented urban customers living in congested cities. With a rise in the number of customers demanding their coffee to be delivered within minutes of ordering (either online or offline), coffeehouse chains, both domestic and international, were scrambling to meet this demand by providing a blend of e-commerce, mobile shopping and brick-and-mortar storefronts.

In response to the success of coffeehouse chains in China, particularly Starbucks, Jenny Qian Zhiya founded Luckin in November 2017. Qian had recognised that the demand for fresh ground coffee in China was growing exponentially, and that coffee had transitioned from being a social lubricator to a lifestyle habit. However, the market was underpenetrated due to high prices and inconvenience in accessing the product. She thus targeted the untapped demand by offering coffee at prices that were about 30 percent lower than the high-end brands like Starbucks and Costa, but higher than McDonald’s and Family Mart, the low-end players associated with lower quality. In addition, Luckin offered a technology-driven retail model comprising online and offline integration that enabled customers to order and pick up from their nearest store, get it delivered, or enjoy it at a café.16 The twin elements of the start-up’s new retail model—low prices and super-speedy delivery—were enabled through its mobile app and wide store network.

The mobile app covered the entire customer purchase process including menu, order, payment and delivery options. Irrespective of the type of order (pick-up, delivery or on-premises), all orders and payments could only be made through the app, resulting in fully cashless transactions. This mobile app-based model appealed to the digitally savvy Chinese consumers, especially the millennials, who preferred using online menus and paying through their smartphones. Other than Luckin’s own ‘coffee wallet’, payment could also be made through third-party payment service providers such as Weixin Pay, Union Pay and the ubiquitous WeChat platform.

Luckin focused on building an expansive store network comprising three formats: pick-up stores (87 percent) consisting of small shopfronts with no or limited seating that largely catered to mobile order pick-ups and delivery, delivery kitchens (8 percent) comprising dedicated kitchens that focused solely on processing and dispatching orders, and relax stores (5 percent) which were café-style stores where customers could sit and enjoy their coffee.17

Most of Luckin’s stores were located in office buildings, commercial areas and university campuses, and were designed for fast pick-up and delivery.18 The company claimed to have achieved 100 percent coverage within a 500 metre radius of central districts in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, with access to at least one store within a five-minute walk in these areas.19

Besides using many of its outlets as kitchens to quickly fulfil the orders placed, Luckin relied heavily on technology for smart ordering and dispatch of deliveries, in collaboration with SF Express, a Chinese courier company.20 Consequently, it claimed that its average delivery time was only about 18 minutes and the coffee was given free if it did not reach its destination within 30 minutes. The tech-based start-up used big data analytics and artificial intelligence to study customer behaviour and transactions in real time to better craft its products and services strategy, implement dynamic pricing, and improve customer retention.21 In addition, Luckin reported that its centralised system helped improve the company’s operational efficiency through standardisation, enabling it to rapidly scale up its presence.

By March 2019, Luckin declared that it had sold more than 90 million cups of coffee across 28 cities and employed a 16,645-strong workforce in the country.22 According to the analysts at Inside Retail Asia, it had taken Starbucks nearly 13 years to achieve the size that Luckin claimed to have reached in just one year.

PRICING, DISCOUNTS AND ADVERTISING STRATEGY

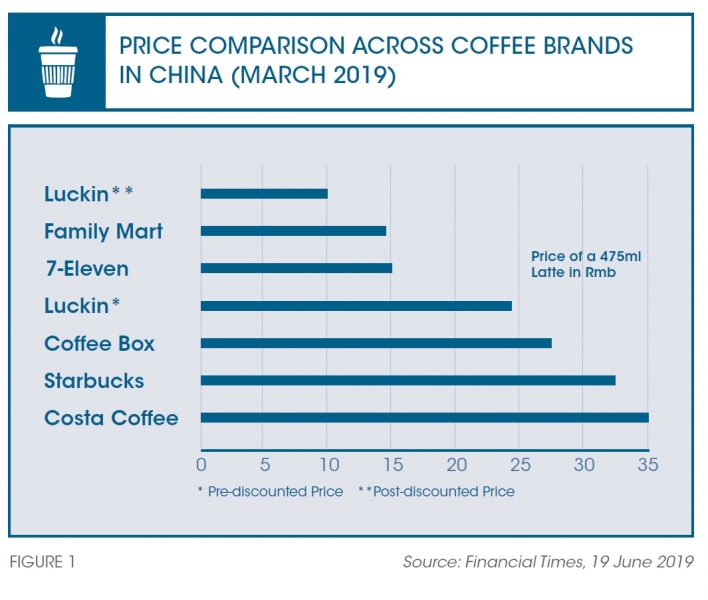

Luckin’s dynamic pricing was based on a low fixed price and flexible discounting strategy. While its latte was priced at about US$3.54 (including a US$0.87 delivery charge) compared to US$4.28 from Starbucks, its aggressive and regular discounts such as free first drink, free drink for recommending the app, free drink for following it on social media, two-for-three, five-for-ten and free delivery above a certain order size, brought its effective selling price down to be the lowest in the market (refer to Figure 1).

In 2018, Luckin reported that it had spent US$111 million or 87 percent of its annual net revenue on advertising and marketing. It signed top-tier celebrities in China, Zhang Zhen and Tang Wei, as its brand ambassadors, and also partnered with foreign baristas such as Andrea Lattuada, former judge of the World Barista Championships, to help build brand credibility.24 According to the company, its app-only model enabled it to have a digital profile of and a digital connection with each of its customers, hence it could implement highly-focused online marketing initiatives.

In 2018, Luckin reported that it had spent US$111 million or 87 percent of its annual net revenue on advertising and marketing. It signed top-tier celebrities in China, Zhang Zhen and Tang Wei, as its brand ambassadors, and also partnered with foreign baristas such as Andrea Lattuada, former judge of the World Barista Championships, to help build brand credibility.24 According to the company, its app-only model enabled it to have a digital profile of and a digital connection with each of its customers, hence it could implement highly-focused online marketing initiatives.

David versus Goliath

David versus Goliath

In view of the rise of Luckin, Starbucks partnered with China’s largest e-commerce conglomerate, Alibaba, in August 2018, to provide ‘Starbucks Delivers’, a service to deliver its beverages within 30 minutes. It linked its 2,000 outlets across Chinese cities with the Alibaba-owned Ele.me, a leading online food delivery site, and aimed to offer the service in about 90 percent of its stores in China within a year.26 Additionally, Starbucks opened its first two delivery kitchens, known as ‘Star Kitchens’, inside Hema supermarkets in Hangzhou and Shanghai, leveraging the supermarket’s logistical capabilities for delivery.

However, there were high costs associated with the delivery channel. Besides the expense of about US$1.04 per order (charged to Starbucks by delivery companies), each Starbucks delivery order required a special double-layered lid to keep the drink hot or cold, spill-proof packaging, and a tamper-proof packaging seal. It also required unique containers that ensured optimal temperature and standards for beverage and food quality, and safety during delivery.27

Meanwhile, Luckin was shoring up its capital. In 2018, the company raised a total of US$400 million over two rounds of financing. Centurium Capital, a private equity fund, and GIC, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, invested the first round of US$200 million. This catapulted Luckin to a US$1 billion valuation in July 2018, within eight months of its operations. Six months later, in December 2018, the second round of US$200 million funding by GIC, China International Capital Corporation (an investment banking firm) and Joy Capital took Luckin’s valuation to US$2.2 billion.28 Buoyed by its market standing, the company raised another US$150 million in April 2019, before its initial public offering in May 2019.29

It was clear that the value propositions the two companies offered were quite distinctive from each other. While Starbucks strived to satisfy the needs of self-indulgence and social gratification, Luckin catered to the functional needs of the mass market through easy, quick and affordable access. Going forward, Starbucks would have to decide on the relative emphasis it should place on emulating Luckin, and work towards building a stronger and wider delivery channel versus continuing to pursue its premium priced experiential retail strategy. Moreover, although Luckin’s success had negatively impacted Starbucks’ growth in the short term, it seemed implausible that its cash-burn business model that includes heavy discounting, aggressive advertising and rapid store expansion could continue without raising an alarm eventually.

This case was developed with the support of Singapore Management University's Retail Centre of Excellence (RCoE). The complete case, published in October 2019, can be accessed at https://cmp.smu.edu.sg/case/4166

Nirmalya Kumar

is Lee Kong Chian Professor of Marketing at Singapore Management University and a Distinguished Fellow at INSEAD Emerging Markets Institute

Dr Sheetal Mittal

is a Senior Case Writer at Singapore Management University

Stephen Eryung Chu

is a DBA student at Singapore Management University

References

1. Desmond Ng, “How Starbucks’ Growth Nearly Destroyed the Business, until One Man Saved Its Skin”, CNA, 26 November 2018.

2. Ibid.

3. Starbucks Corporation Annual Report 2008.

4. Aimee Groth, “19 Amazing Ways CEO Howard Schultz Saved Starbucks”, Business Insider, 20 June 2011.

5. Marianne Wilson, “First Look: Starbucks Debuts Premium Store Format”, CSA, 27 February 2018.

6. Jessica Tyler, “Starbucks Just Opened a Reserve Roastery in New York that has a Full Cocktail Bar and is Almost 13 Times the Size of the Average Starbucks. Here’s How it Compares to a Typical Starbucks”, Business Insider US, 17 December 2018.

7. Wang Zhuoqiong, “Starbucks Laser-focused on China Market”, China Daily, 2 March 2018.

8. Lisa Fu, “The Starbucks Experience in China is Way Different than in the US (SBUX)”, Markets Insider, 18 May 2018.

9. Michael Zakkour, “Why Starbucks Succeeded in China: a Lesson for all Retailers”, Forbes, 24 August 2017.

10. Ibid.

11. Ding Yining, “China Brews Bubbly Future for Starbucks”, Shine, 2 January 2018.

12. Starbucks Stories, “Starbucks Debuts Mobile Payment Experience in China”, 12 July 2016.

13. Jaime Toplin, “Starbucks Adds Alipay in China”, Business Insider, 27 September 2017.

14. Lisa Fu, “The Starbucks Experience in China is Way Different than in the US (SBUX)”, Markets Insider, 18 May 2018.

15. Russell Flannery, “Meet the Woman behind Starbucks in China”, Forbes,1 March 2017.

16. Savannah Dowling, “Luckin Coffee Raises $200M More, Doubles Valuation”, Crunchbase News, 12 December 2018.

17. Luckin Coffee, IPO Prospectus Report, 23 April 2019.

18 Tianyu Fang, “How Luckin Coffee is Reforming China’s Coffee Culture”, technode, 30 July 2018.

19. China.org.cn, “Luckin Coffee Appoints Reinout Schakel as CFO, CSO”, 7 January 2019.

20. Nisha Gopalan, “Starbucks, There’s a Unicorn in Your China Shop”, The Washington Post, 3 December 2018.

21. Luckin Coffee, IPO Prospectus Report, 23 April 2019.

22. China.org.cn, “Luckin Coffee Appoints Reinout Schakel as CFO, CSO”, 7 January 2019.

23. Hunter White, “Luckin vs Starbucks: Technology Storm in a Coffee Cup”, Inside Retail Asia, 18 January 2019.

24. Paula Thomas, “Coffee Goes Cashless in China”, Liquid Barcodes, 20 July 2018.

25. Amelia Lucas, “Starbucks CEO Calls Chinese Rivals’ Use of Discounts Unsustainable as Luckin Coffee Prepares for IPO”, CNBC, 26 April 2019.

26. Julie Wernau and Julie Jargon, “Starbucks Fights Hot Startup in China”, The Wall Street Journal, 13 March 2019.

27. Starbucks Newsroom, “Starbucks Accelerates Delivery Service Coverage to Bring Best-in-Class Coffee Delivery Experience to More Customers in China”, 18 October 2018.

28. Rebecca Fanning, “Starbucks Rival Luckin Coffee in China Aiming High with IPO Plans in the Offing”, Forbes, 4 March 2019.

29. Julie Zhu and Pei Li, “Starbucks’ China Challenger Luckin to Raise up to $800 Million in U.S. IPO: Sources”, Reuters, 23 April 2019.